Point Isabel: Birding Hotspot

By Jess Beebe

Most people think of Point Isabel primarily as a dog park, and indeed it features one of the largest and most scenic off-leash dog areas anywhere. But this park is also the gateway to a premier birding destination, offering access to a delightful stretch of the San Francisco Bay Trail that meanders through a restored salt marsh and slough and past expansive mudflats.

Tires, shopping carts, and chunks of concrete remind us that this place – like many shoreline parks – has a checkered history of human use. (It was acquired by the East Bay Regional Park District in 1975 to offset the construction of the neighboring Postal Service facility.) Here, as elsewhere, the Bay Trail runs parallel to a busy freeway. Yet the place has a wild beauty that transcends the heavy impact by people, both past and present, and makes it a worthwhile destination even for nature lovers who generally prefer more pristine places.

The mudflats and salt marsh provide outstanding habitat for shorebirds year-round and ducks in winter. Upland habitat hosts warblers and other songbirds. But without a doubt, the star resident is the Ridgway’s Rail. This species was known as the Clapper Rail until 2014, when the West Coast population was declared distinct from Gulf and Atlantic populations and given its own name. The interpretive displays along the Bay Trail still refer to the birds as Clapper Rails. Whatever you call this species, it is classified as endangered, both federally and in California, mainly due to habitat loss.

Tidal channel west of the Bay Trail near Point Isabel / Photo by Jess Beebe

Tidal channel west of the Bay Trail near Point Isabel / Photo by Jess Beebe

Ridgway’s Rail (formerly California Clapper Rail / Photo by Bob Lewis

Ridgway’s Rail (formerly California Clapper Rail / Photo by Bob Lewis

Rails are known for their secretive habits. They spend much of their time hidden deep in the salt marsh, venturing out onto the muddy banks of the channels only occasionally, and often for just moments at a time, before disappearing back into the marsh.

I saw my first Ridgway’s Rail on a trip to the Upper Coast of Texas. A fellow birder had told me that they could reliably be seen alongside a certain road on the Bolivar Peninsula. Determined to finally lay eyes on one of these elusive birds, I brought a sandwich and staked out the muddy marsh edge. About two hours later, a rail appeared. Having seen that rail – if only briefly – I felt more confident searching for them at Point Isabel, and later that season I spotted one there, too.…

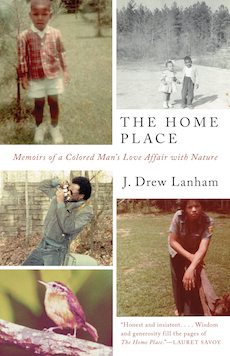

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book