How to Thrive as an SOB (Spouse of Birder)

By Kim Marvel

Birding at a natural area near our home in Fort Collins, Colorado

Birding at a natural area near our home in Fort Collins, Colorado

My wife is a birder. The early signs were subtle. Years ago, she requested my assistance placing feeders and nesting boxes in our backyard. On occasion she signed up for local birding walks. She populated our landscaping with bird-friendly shrubs and trees. Her growing interest became more evident when she placed a heated bird bath on our back deck in the winter. Now, in her retirement years, she’s completely out of the closet as a fully-fledged birder. The kitchen counter is piled with binoculars, spotting scopes, birding magazines, and Feeder Watch forms. National Audubon and the Cornell Lab are on the top of our charitable contributions list. We are frequent flyers at the local Wild Birds Unlimited store. At home, the top of each hour is cheerfully announced by a bird song emitting from the Audubon wall clock. Merlin is among her phone apps. She routinely opens her laptop to update her e-Bird list. As I write this, the centerpiece of our dining room table is a partially completed bird-themed jigsaw puzzle. Nowadays, our road trips are often organized around birding hotspots. Yes, it’s safe to say birding has become her favorite activity.

View from Golden Gate Overlook during a recent visit to San Francisco

View from Golden Gate Overlook during a recent visit to San Francisco

I’m not a birder. Don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy watching a colorful hummingbird or spotting a majestic raptor soaring above. On a recent outing, I was enthralled by the unique courting ritual of the Greater Prairie Chicken. Indeed, it is satisfying to recognize a species or common birdsong. It is not that I dislike birding. I just don’t have the innate curiosity and interest that I witness in my wife. I don’t have the “fire in the belly” that I observe in birders, particularly when they gather in groups. Try as I might, I don’t experience the sheer delight in my wife’s eyes upon seeing a new species.

Being a “birder”, of course, is not an either/or quality. At one extreme of the “bird interest” scale are people oblivious to bird activity. Others, like me, have a modest interest. We can recognize iconic birds such as the bald eagle, robin, cardinal, and great horned owl. While we enjoy spotting a colorful bluebird or hearing the cheerful song of a meadowlark, our interest in ongoing observation or detailed classification of species fades quickly.…

Stanfordians become the avians at Vollmer Peak.

Stanfordians become the avians at Vollmer Peak.

Black Turnstone at Cesar Chavez Park. Photo Credit: Zihan Wei

Black Turnstone at Cesar Chavez Park. Photo Credit: Zihan Wei

As usual, Sara noticed it first: the freckle in this White-tailed Kite’s right eye. Photo: Sara Sato

As usual, Sara noticed it first: the freckle in this White-tailed Kite’s right eye. Photo: Sara Sato

As usual, Sara noticed it first: the freckle in this White-tailed Kite’s right eye. Photo: Sara Sato

As usual, Sara noticed it first: the freckle in this White-tailed Kite’s right eye. Photo: Sara Sato

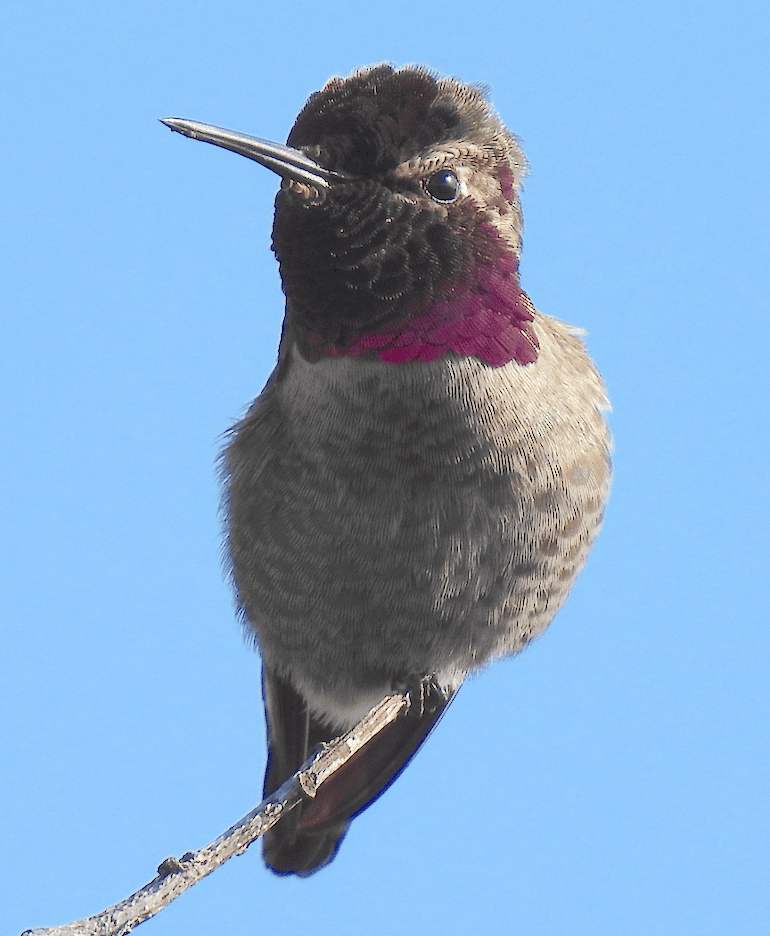

The iridescent patch on the throat of Anna’s hummingbirds is called a gorget, maybe because it’s gorgets — er, gorgeous. (I’ll show myself out now.) Photo: Sara Sato

The iridescent patch on the throat of Anna’s hummingbirds is called a gorget, maybe because it’s gorgets — er, gorgeous. (I’ll show myself out now.) Photo: Sara Sato

Great Horned Owl photographed during the Bay Birding Challenge, part of Birdathon 2023. Photo: Tara McIntire

Great Horned Owl photographed during the Bay Birding Challenge, part of Birdathon 2023. Photo: Tara McIntire

Marilyn Rose and James Blackstock

Marilyn Rose and James Blackstock

Out of this World

Out of this World