Black Oystercatcher nesting success at Heron’s Head

By Mary Betlach

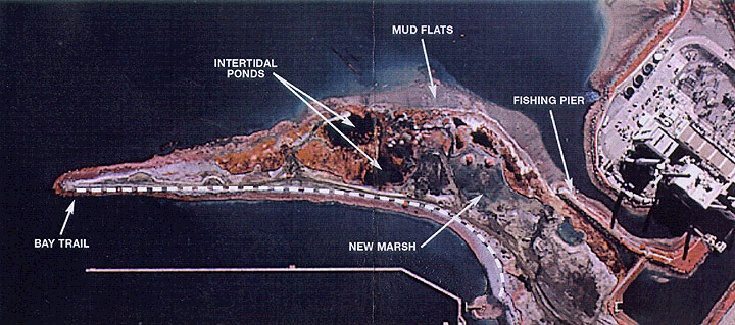

I’ve walked at Heron’s Head Park on San Francisco’s southeastern shoreline since 2005 and casually observed juvenile Black Oystercatchers there most years. One of our most distinctive shorebirds because of their bright orange bills, oystercatchers are at risk because of the dwindling amount of rocky shoreline they need for nesting. They’re already designated a Species of Special Concern by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and climate-related sea level rise will only heighten their breeding challenges.

This year, Golden Gate Bird Alliance created a Heron’s Head Monitoring Group to gather data on the Black Oystercatchers there – myself, Annie Armstrong, Patricia Greene, and Tim and Alexia Tindol. We had the privilege of watching a pair raise a chick on a dilapidated pier about 65 yards from the shoreline in the center of Lashlighter Basin.

(Another Golden Gate Bird Alliance member monitored Black Oystercatchers at Land’s End in San Francisco in 2015 as part of an ongoing Audubon California survey of the species: You can read about it here.)

We started our monitoring on March 31, observing the shoreline area twice a week in teams of two. We quickly realized that the old pier is an ideal location for a Black Oystercatcher nest. It is close to rich feeding grounds along the rocky shoreline and separated from ground predators by the surrounding water. It’s high enough above the water to avoid flooding, yet both remaining ends of the pier provide a gentle slope to the water. The height of the pier facilitates a 360-degree view of the surrounding area, giving the adult oystercatchers optimal surveillance against airborne predators. The pier has numerous cross beams and other decaying structural features that provide cover for the nest and hatchlings.

There are several potential airborne predators at this site. A Western Gull colony nests nearby on the roof of the Recology building. (Fortunately, the gulls hatched at a point when the oystercatcher chick was most likely too big for dinner).

Other predators were American Crows, which approached the pier fairly closely and were chased by the adult oystercatchers. There were also Common Raven, Osprey, and Peregrine Falcon flyovers. Rock Pigeons also walked the pier and were chased off by the Black Oystercatchers. Several times we observed a third adult oystercatcher that was also chased off.

We could not see the nest itself from our vantage point on the shore, but in late April we observed nest-building activity on the pier and in mid-May we saw adult oystercatchers incubating at that spot. The nest was quite well hidden down inside a beam cavity, but the adult bird’s head and orange bill were just visible from the shore.

We first saw the chick on June 9. The pier was an ideal place to spend the very vulnerable early weeks of life. It was out of the wind, the dark gray chick blended very well with the weathered beams, and the many pieces of debris provided places for the chick to hide. The flat center and sloping ends provided an extensive area for the chick to run around without danger of falling and a gentle slope where there was also access to the water. At low tide, the western side of the pier sloped directly toward the rocky mudflat feeding areas, but was still separated by a short stretch of water. This was the area wherewe first saw the chick “escape” from the safety of the pier.

The parents were very attentive, rarely leaving the chick alone, and then only briefly. Since they had only one chick to watch, it may have been easier for them. One parent would chase off possible predators or go to forage and the other one stayed with the chick. They alternated these duties. The on-duty parent was frequently seen on the pier, often perched on the top horizontal beam (with the 360-degree view) with the chick hidden below on the flat part of the pier. The juvenile was good at hunkering down and hiding. At one point when the three were on the beach and people approached, the parents flew off to the pier and the juvenile hunkered down and blended in.

We first spotted the chick away from the pier on July 15, on the rocky beach, where it could either have flown or swum. On July 18, we observed it in flight. We spotted the whole family foraging along the Heron’s Head Park shore several times in late July, and ton August 2 found them at nearby Pier 94 – the former dump site that Golden Gate Bird Alliance is restoring as wildlife habitat.

Our observations demonstrate that the pier is a very productive nest site. However, it’s in danger of collapse. Perhaps efforts can be made during the off-season to shore it up.

The characteristics of the pier may also provide an excellent model for other sections of coastline where sea-level rise is threatening Black Oystercatcher nesting sites.

In the future, closing the Heron’s Head beach area to dogs and people during fledging season would help the chick during the short period when it has left the pier but is not yet a confident flyer. If closure is not an option, signs should be posted to warn people to pay attention to the birds and not disturb them.

Heron’s Head Park is used regularly by many neighbors, and any time we talked to them, even the non-birders were aware of and loved the oystercatchers. There is a leash policy at Heron’s Head, although it is not always obeyed. One dog walker heading for the beach was quite agreeable to adjusting his route to take care of the Black Oystercatcher family. Adding seasonal signage could have a positive effect on this subset of the population and help ensure that young oystercatchers have a good shot at reaching adulthood.

Mary Betlach, a member of Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s San Francisco Conservation Committee, is a retired PhD Biochemist and a Master Artist in the Mary L. Harden School of Botanical Illustration. . Her artwork is currently on display in the Lepidoptera exhibit at the UCSF Faculty Alumni House, 745 Parnassus Avenue, until January 8, 2018.