Japanese tsunami debris at Pier 94?

By Ilana DeBare

GGBA Volunteer Coordinator Noreen Weeden was birding recently at Pier 94, the old San Francisco dump site that we’ve restored as wetlands habitat, when she found an unusual piece of washed-up trash….

A plastic candy box covered with Japanese writing.

Noreen wondered if this might be debris from the March 2011 Japanese tsunami. She contacted NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which monitors marine debris.

It turns out that tsunami debris began washing up on beaches in the Pacific Northwest last winter. Although most of it is still concentrated out at sea, NOAA predicts that some debris will start reaching the rest of the West Coast this winter. (See chart at bottom of this post.)

The agency couldn’t say for sure if this particular plastic box came from the tsunami. Buoys and litter from Asia end up on U.S. beaches all the time.

But Noreen’s mystery is a reminder about our modern, self-inflicted plague of marine debris. Most common plastics don’t completely break down in water. Instead, they shred into little particles that are eaten by fish, turtles and seabirds.

Plastic can damage the digestive systems of fish and seabirds. Or if plastic remains in their gut, they may feel full and stop eating, leading to malnutrition or starvation. Researchers estimate that nearly all of the 1.5 million Laysan Albatross on the Midway Islands have plastic in their gut. About one-third of the albatross chicks die, many from eating plastic debris that their parents mistake for food.

Meanwhile, large pieces of plastic debris such as bags or nets can trap fish and other sea life. And there are still other unknown effects from the release of chemicals like PCBs that are components of plastic — and that travel up the food chain as fish are eaten by larger predators.

That’s why we support efforts to limit the use of disposable plastic bags, like the Bay Versus Bag campaign run by our friends at Save the Bay. They estimate that more than 1 million plastic bags enter the San Francisco Bay each year.

And that’s why our Eco-Education staff makes it a priority to teach students about plastic debris. In 2011, we were able to send one of our high school interns to the 5th International Marine Debris Symposium in Hawaii.

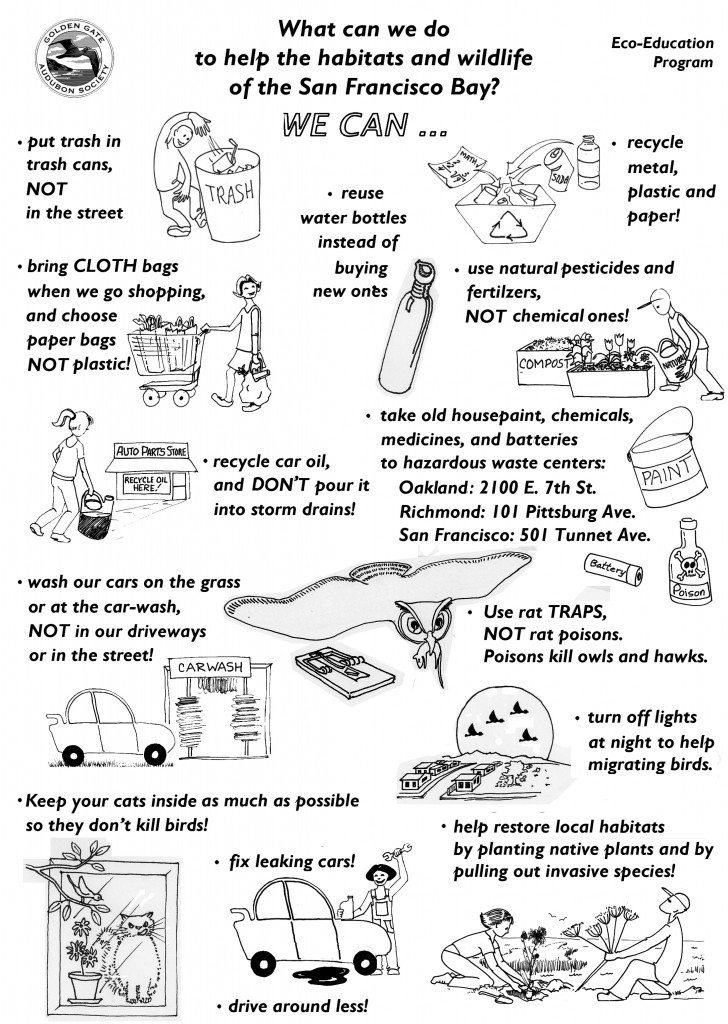

When our Eco-Ed staff lead elementary school families on field trips to the beach, they have the kids collect garbage and try to guess the decomposition timeline for each piece. They show them a diagram of a storm drain leading from their neighborhood into the Bay. They hand out posters in Spanish and English of actions that we can all take to protect wildlife and habitats (see below).

“Eighty percent of marine debris is land-based litter — trash that enters storm drains or gets blown into the Bay,” said GGBA Eco-Education Director Anthony DeCicco. “We want them to come away knowing why they shouldn’t litter.”

————————–

Alameda County will take a step towards reducing plastic bag debris on Jan. 1, 2013, when it will join San Francisco, San Mateo County, San Jose and 49 other California cities and counties in no longer providing single-use plastic bags at checkout. Instead, Alameda County residents will be asked to bring reusable bags from home or pay 10 cents or more for paper bags.

Want to learn more about marine debris? See NOAA’s Marine Debris web pages. Or see the Algalita Marine Research Institute’s web site.