Visiting Castle Rock breeding bird colony

By Patricia Bacchetti

Early May marks the occurrence of Godwit Days, the annual birding festival in Arcata, in Humboldt County. By doing some advance planning this year, I was able to register and attend this well-run event with friends. Be warned: The popular trips fill quickly, so check out the schedule in February if you are planning to attend. The highlight of the trip, in addition to David Sibley’s keynote address Saturday night, was a two-day trip from Arcata to Brookings, Oregon, along a stretch of the coast that I’d never birded before.

One of our first stops was the picnic grounds at Wilson Creek, off Highway 101 just north of the Del Norte County line. A beautiful pair of wintering Harlequin Ducks was resting under the bridge: It’s a species that’s always hard to find in the state, particularly in pairs. They used to breed in rushing streams in the western Sierra, but haven’t been documented for years. This pair was likely heading north to Alaska to breed.

Our next stop was Castle Rock National Wildlife Refuge, one-half mile off the coast near Crescent City. The fourteen-acre rock hosts the second-largest colony of breeding seabirds south of Alaska, surpassed only by the Farallon Islands breeding colony. Common Murres are the most numerous species, and the rock is considered their largest breeding colony on the coast of California. They’re joined by small numbers of Tufted Puffins, Pigeon Guillemots, all three cormorant species, Rhinoceros and Cassin’s Auklets, Western Gulls, and both Leach’s and Fork-tailed Storm Petrels. Northern Elephant Seals and Harbor Seals also breed on the island. Aleutian Cackling Geese have made the island a night roost, and they fly out to the pastures of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties to feed during the day.

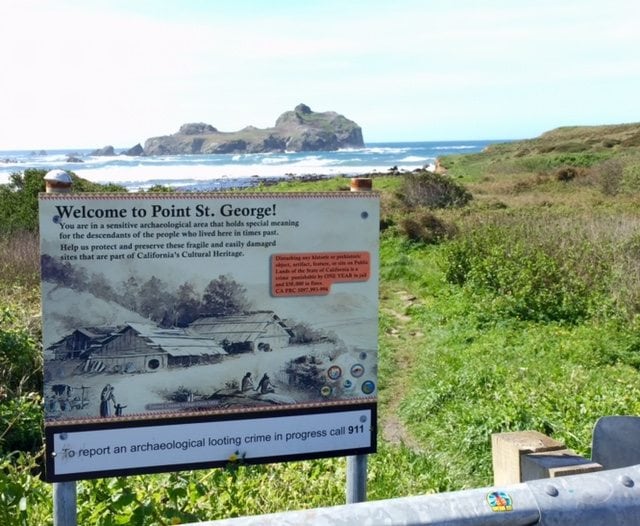

Castle Rock was privately owned until 1979, when it was acquired by the The Nature Conservancy. Recognizing its importance for breeding sea birds on the north coast, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bought the island and put it into the National Wildlife Refuge program in 1980. Besides Southeast Farallon Island, it’s the only other off-shore National Wildlife Refuge in California. The rock was an important foraging site for the local Tolowa people in times past, and that history is commemorated at the Point St. George entry site.

We went to Castle Rock hoping to see Tufted Puffins at their breeding burrows, but because they’re actively feeding in the water during the day, we didn’t find any that day. The group that went out early in the morning of the next day was able to find two or three pairs on the grassy part of the island. Common Murres, Pigeon Guillemots, cormorants, and gulls were also readily visible.

What was more interesting was what was not visible.

There are four species that burrow-nest, fly out to the ocean to feed during the day at sunrise, and only return near dark to feed young or relieve the other parent: Rhinoceros and Cassin’s Auklets, and Leach’s and Fork-tailed Storm Petrels.

While airplane surveys can get a good view of the species that are visible during the day, it’s harder to estimate the numbers of the night-active species because people tramping around can damage burrows and destroy nests. A California Fish and Wildlife Seabird Breeding Colony Survey done in 1992 found that Castle Rock was the largest breeding colony of Rhinoceros Auklets in the state; it probably still has a substantial colony. Humboldt State University subsequently conducted a multi-year study with night cameras and thermal imaging, illustrating the difficulty involved in studying such cryptic species.

The Aleutian Cackling Geese, until recently a federally-listed Endangered Species, paradoxically pose a problem for the fragile populations of the burrow-nesting species. The geese, a smaller relative of the more common Canada Goose, were thought to be extinct until 1967. Then a small colony numbering in the hundreds was found on Buldir Island in the Aleutian Islands.

The colony was being threatened by Arctic and Red Foxes that had been introduced by Russian fur trappers in the 1700’s. Efforts to rid the islands of predators and to protect their wintering grounds further south led to a rapid rebound in their population. By 1991, it was estimated that the population was over 100,000 birds, and they were taken off the Endangered List. The pastures of the north coast and the flooded fields of the San Joaquin-Sacramento Delta host large numbers of Aleutian Cackling Geese in the winter. Over 20,000 geese spend the night on the Castle Rock, and can trample burrows and shorten the grass that helps protect breeding sea bird nests. (If you would like to see these beautiful little geese locally, The Nature Conservancy’s Staten Island property in San Joaquin County hosts thousands of them in the winter months.)

We birded our way to Brookings, where we spent the night, then headed back to Arcata the next day. There are several interesting places to stop along the way: Highlights included a nesting Bank Swallow colony at the Smith River, a Common (or Eurasian) Green-winged Teal at the Alexandre Dairy Ponds, and Gray Jays in the hills above Crescent City.

The North Coast, in addition to being one of the most beautiful parts of the state, also offers excellent birding opportunities, good spots to eat, and several well-made craft beers. Godwit Days is a birding festival worth attending if you get the chance, with many trips offered and good leaders. It was also fascinating to learn about the large sea bird colonies at a location more accessible than the Farallons. Visit Castle Rock if you can.

Click here to view a live web cam of nesting sea birds at Castle Rock National Wildlife Refuge. (Webcam operates seasonally during the daytime, based on weather conditions, between April and August.)

When not birding, Pat Bacchetti practices veterinary medicine in the East Bay. She learned how to bird eleven years ago by taking classes from and field trips with Golden Gate Bird Alliance