Enjoy Our Wintering Birds While You Can

By Lee Friedman

[Note: If you cannot see the accompanying photographs or if they are blurry, please click on the title or the “read in browser” link to view this blog on the GGBA website.]

“While you can” refers to the next few months, after which our wintering migrant birds will depart to their breeding grounds elsewhere and be gone until fall. But it could also refer to the longer-run sustainability of bird migration patterns as our global climate changes. None of us knows when one or more migrating species might find it necessary to change their migratory patterns simply in an attempt to survive. White Storks that breed in Europe, for example, are already forgoing their traditional African wintering ground and choosing to migrate a much shorter distance within Europe. Perhaps some of the migrant species of birds that we can see today (and in the next few months) might not be returning in comparable numbers in future years. But they are exquisite to see and to appreciate now, while we are privileged to have them.

Bird species in one geographic location are generally classified into one of two categories: residents that are year-round, and migrants that are there for only part of the year. Within the migrant category, there are the birds that are generally there during the summer to breed but elsewhere during the winter, and the wintering migrants that arrive in the fall and leave in the spring to go elsewhere to breed. The focus of this post is on the wintering migrants (those here now). There are other more transient types of migrants as well: those that may regularly pass through our area on their way to their breeding and/or wintering areas (e.g. Hermit Warbler, Black-throated Gray Warbler), as well as “vagrants” that we don’t really expect but show up occasionally perhaps because they have gotten off course (e.g. a Summer Tanager seen from last October to January in the Claremont Canyon Regional Preserve). But back to the wintering migrants—it might be natural to think of them as visitors, but ornithologists think that they are descended from those who at one time were full-time residents of the winter grounds. In other words, the wintering birds are simply returning to their ancestral homes. More reason to appreciate them, I think.

What are the wintering species? I’m going to describe a few of my favorites, chosen to illustrate differences in migration patterns and the different parts of the world they rely upon in addition to our own. I will also use species that are all present in Tilden Regional Park, as a way of trying to convey the majesty of our park habitats that can support such an incredible diversity of avian wildlife. However, these species can also be found at many of our local birding hotspots, so I will first describe briefly how anyone can check their favorite public birding area to see what wintering species are there, and for what duration.

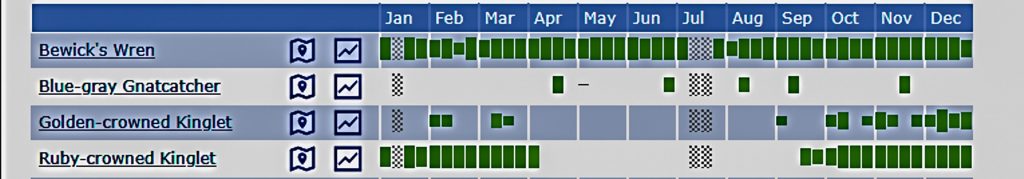

I make use of Cornell University’s free eBird.org website. Under the “explore” section, choose “Explore Hotspots” and then type in the name of a park or birding hotspot that is of interest to you. For example, if you type “Tilden” you will see a list that begins with a number of east coast areas, but scroll down and you will see a number of listings for Tilden Nature Area and Tilden Regional Park in Contra Costa, CA. I will choose the Tilden Nature Area as a specific example. It shows a map with a pop-up box for the Tilden Nature Area, and then choose “View Details.” This brings you to a page showing a list of the species sighted most recently there, but click the “Bar Charts” link at the top of this list. A page appears with a bar chart for each species ever reported there. The chart divides the year into 48 “weeks” and shows the probability of a birder seeing that species during each week. Jot down those species that show “green” most of the year but are blank (not observed) for three or more of the summer months; those are the wintering species. Note that a gray bar is not the same as blank; it means no information is available for that time because no checklists were submitted. The taller the green bars, the more abundant is the species at that time and location, and the higher the probability that a birder will observe one or more of them. Here is an illustration of a few of the listings from the Tilden Nature Area example:

Figure 1: eBird Bar Charts for 4 Species observed at the Tilden Nature Center

Of the four species shown, the Bewick’s Wren is a full-time resident (the three gray bars are repeated for all species because no checklists were submitted for those weeks; they don’t mean that the Wren wasn’t there). The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher has been observed here too infrequently to identify a seasonal pattern with any confidence. Its 5 green bars are spread out from April-November with many blanks between them; this is suggestive of a hard-to-find breeding resident but the blanks from December-March might be simply because it is hard to find. (eBird in fact treats it as a breeding migrant, although its presence has been detected in Tilden Christmas bird counts and elsewhere in our region during the nonbreeding season, including EBMUD Valle Vista and the SF Bay Trail by the 51st St. area in Richmond). Both of the Kinglet species fit the nonbreeding wintering pattern—there are no reported observations of them here from May-August. You can also see that the Ruby-crowned Kinglet is far more abundant (more and longer green bars) than the Golden-crowned Kinglet. The longest bar means that 60-100% of birders submitting their checklists saw (or heard) one or more birds of this species, and the percentage decreases as the bar gets shorter. Thus birders from now through March have very good chances of actually seeing the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, whereas the much shorter bars and some blank weeks for the Golden-crowned Kinglet during the same period mean that only about 10% of birders see it then (but hey, a 10% chance is better than nothing).

Now that we’ve reviewed how eBird may be used to find out which wintering bird species are in any hotspot of interest to you, here are some examples of these birds with brief notes about each.

One of my favorite wintering species is the Townsend’s Warbler (see Photo 1). The Townsend’s breeds primarily along the western coastal range of Canada (some in the northwest U.S.) and when it leaves us for these breeding grounds, it actually doesn’t leave for very long. It usually can be seen here through May, generally not in June or July, and then it reappears sometime in August. This implies it must do its breeding with dispatch! The entire period from the beginning of its nest construction, laying and hatching of eggs, and the fledging of the young is about one month. Soon thereafter, the birds depart back to their wintering areas. They are considered long-distance migrants (over 2000 km) and winter along the entire west coast as well as parts of Mexico and Central America, so I feel especially grateful that these beautiful globe-trotters continue to find our neck of the woods hospitable.

Another one of my favorite wintering species is the Red-breasted Sapsucker. It is the only woodpecker in our area with an all-red head, the red extending to its breast (see Photo 2). This one is not as abundant as the Townsend’s Warbler, so it might take more effort to find one. One type of tree that they seem to love is the cotoneaster, and the bird in the accompanying photograph is on one. Note the large number of tiny holes drilled in this tree. If you see a cotoneaster with these holes, there is a good chance that a sapsucker was, and may still be, a regular visitor to it. The holes are sap wells; they are shallow, as this is all that is necessary for the bird to access the tree’s sap for food. The Red-Breasted Sapsucker is generally only here through March, when it then departs for its breeding grounds with return to our area usually by October. Unlike the Townsend’s Warbler, the Red-breasted Sapsucker is generally a short-distance migrant. The species is characterized by partial migration. Many of them, like those living on the west coast north of the Bay Area, do not migrate—they are year-round residents up there. But those wintering in the Bay Area migrate inland somewhat, with a number breeding in the eastern portion of the state.

A third species that winters with us but departs for breeding is the Fox Sparrow. It is slightly larger than the Song Sparrow and most other sparrows in our area, generally brownish with a slightly redder tail, and it has a heavily-marked chest with marks that look like a series of dark triangles (see Photo 3). They appear in most of the U.S. except for the interior western states. There are four different subspecies of the Fox Sparrow, and the subspecies most common in the Bay Area is the unalaschcensis group or “Sooty.” Our subspecies, somewhat like the Townsend’s Warbler, does its breeding along the Pacific coast of Canada and Alaska (Townsend’s will breed further inland in these areas). It is an abundant species through February, after which its numbers decline and it is generally not seen from May-August. Compared by miles travelled to the Townsend’s Warbler, our Fox Sparrow is a mid-range migrant: when choosing its wintering ground, it restricts itself to the Pacific Coast and generally will not migrate much beyond the southern California U.S. border (some go into Baja). However, it is believed that our local Bay Area population migrates directly over the ocean from Alaska, which places it among the longest ocean crossings undertaken by any land birds (see Birds of North America online).

Another of my favorite wintering species is the Hermit Thrush (see Photo 4). They begin to leave in March, and return during September and October. Interestingly, the Breeding Bird Atlases of Alameda and Contra Costa counties have documented instances of the Hermit Thrush breeding in our area. These breeding instances are quite unusual, however, and standard field guides and Birds of North America list it as “winter only” for us. eBird historical observations confirm, using all of well-birded Tilden Regional Park as an example, that there are no submitted observations of this species in June, July, and August, with only small numbers reported in the surrounding months of May and September. In other words, even the most astute and experienced birders are unlikely to encounter a Hermit Thrush in our area during the breeding months. The Hermit Thrush, like the Red-breasted Sapsucker, is a short-distance migrant. They are found throughout North America and in Central America, but ours have one of the shorter migratory routes. They leave us to go eastward and breed in the mountain areas of our own state. A strikingly similar species, the Swainson’s Thrush, breeds in some of the same habitat used by our Hermit Thrush. It is almost as if they are time-sharing. Both are about the same size, with olive-brownish backs, spotted breasts, and whitish eyerings. One place that the Swainson’s Thrush inhabits is the area around Tilden’s Jewel Lake, but only during the breeding season. The Hermit Thrush can be found in the same area but only during the non-breeding season. During the summer, visitors to Jewel Lake often hear the hauntingly beautiful song of the Swainson’s Thrush, and because this species prefers to remain cloaked by the foliage, it is more often identified by sound than by sight. The Hermit Thrush also has a hauntingly beautiful song, but the song is rarely if ever heard around Jewel Lake because this species rarely sings during the nonbreeding months. The Hermit Thrush does call while at Tilden, and is also more prone to perching in the open (often near or on the ground) than the Swainson’s Thrush. But whether you see or hear one of our area’s two Catharus thrushes, you’ll know which one by the season.

Most of our water birds are wintering migrants. One of these species that is always a treat to see is the Hooded Merganser. Unlike the other species I have used as examples, the male and female Hooded Mergansers are strikingly different in their appearance (Photos 5 and 6). The male is very colorful, and it is his excuse for getting out of nest duty on the breeding grounds (he’s too conspicuous). The female is also quite attractive, although in a much less conspicuous way. This species, like the Red-breasted Sapsucker, is characterized by partial migration. In substantial areas of the eastern U.S. and on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border by the west coast, the Hooded Merganser is a year-round resident. In our area, they tend to like smaller freshwater ponds surrounded by forest, like Jewel Lake in Tilden Regional Park. They generally arrive by November, and depart during March and early April. When they leave us, they are thought to go up north to join the resident population there. I don’t know how they decide, come fall, which ones stay and which ones migrate to our area—but I’m glad that some do migrate to us!

One last wintering species that I’d like to mention is the Varied Thrush (Photo 7). Somewhat like the Fox Sparrow, they are largely mid-range migrants that occupy only the western-most states and provinces of North America with some in northern-most Baja. Their breeding grounds are primarily in Canada and Alaska. Like the Red-breasted Sapsucker and the Hooded Merganser, there is a non-migrating population of Varied Thrushes; these are along the coasts of Canada, Washington, and Oregon, with a few extending to the northern-most coast of California. The migrating birds do so in a manner referred to as “leapfrog” migration, in which those in the northern-most breeding grounds migrate to the southern-most wintering grounds. So our Varied Thrushes probably come from lower Canada rather than Alaska. One intriguing aspect of them, at least in recent years, is that their abundance in our area has varied (no pun intended) dramatically from year to year. In the winters of 2015 and 2018, birders reported about 4 Varied Thrush per hour of birding throughout Tilden. But in the winters of 2016 and 2017, they only reported about 1 Varied Thrush per hour of birding. I believe the current winter of 2019 will be on the low side as well. What explains these large differences in abundance from year to year? One factor is that this species is subject to migration irruptions: periodically for reasons that are not very well understood, substantial portions of its population leave the breeding grounds and fly well outside of the normal wintering areas. In irruption years, Varied Thrushes are sighted in the Great Lakes region of the U.S. and even the northeast coast from Maine to New York! Even in non-irruption years, the Varied Thrush is said to be quite sensitive to the abundance of acorns, a staple of their winter diet. So for those of us who like to see the beautiful Varied Thrushes, let’s keep the acorn supplies up!

I hope that this post about our wintering birds is both informative and motivational to seeing and to protecting them. They are ancestral to our area, their migratory habits may be especially challenged by climate change, they are beautiful, and at least for the next few months, they are here!

Lee Friedman is Professor Emeritus of Public Policy at UC Berkeley, and an avid birder and bird photographer.