My personal Pinnacles condor experience

By Richard Neidhardt

The California Condor and support for its recovery at Pinnacles National Park have captured much of my time over the last 5½ years.

This blog tells you a bit about my personal experiences with the condors of the Central California flock, a group of about 70 wild birds that make their home in the mountainous range between Big Sur and the San Joaquin Valley.

About the California Condor

When put into context, the California Condor tale is a success story. Condors have been in North America since pre-history and were first recorded in Monterey in 1604. But by 1982, due to human interference with nature, only 22 California Condors remained in the wild. In 1984, the federal government joined with many private groups in a massive initiative to save the condor from extinction through protective breeding practices.

Today, about 400 California Condors are alive, with over half of them living in the wild in Southern California, Baja Mexico, Central California, and Arizona/Utah.

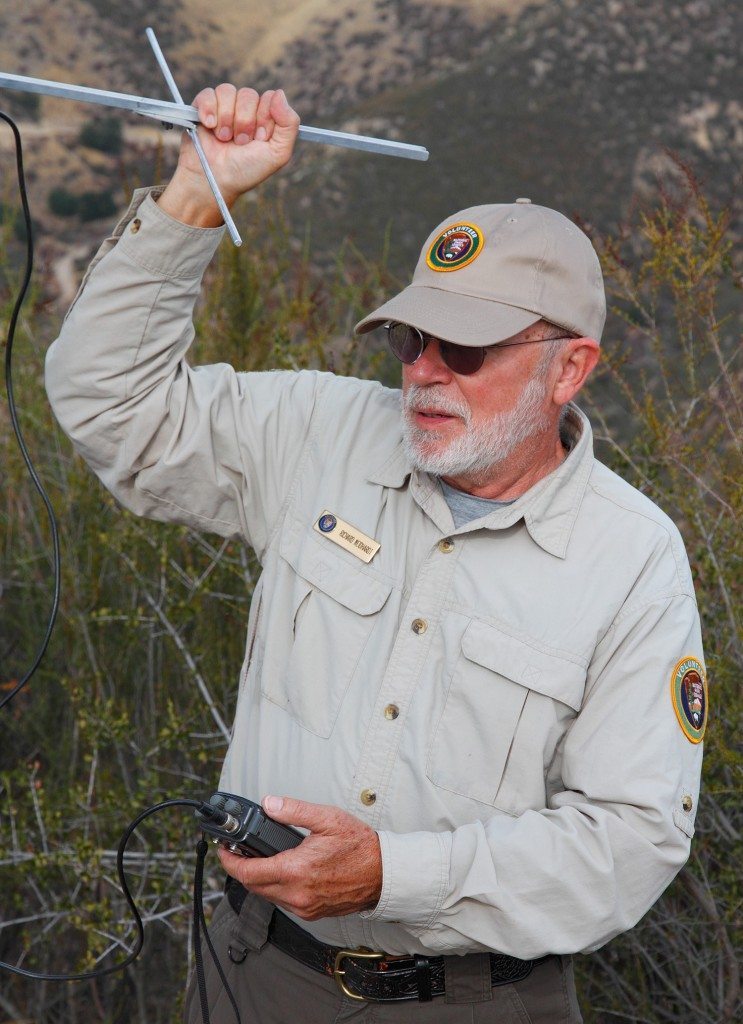

Photo by Sara Bartels

While this is great news, the California Condor remains a highly endangered species. The stark truth is that without help from mankind to repair past damage, address current threats like the use of lead ammunition, and provide vigilant monitoring and support, this awesome icon – the largest bird in North America – is unlikely to fully recover the strength to become a self-sufficient species.

Life as a Condor Recovery Program Volunteer at Pinnacles NP

This is where I come into the story.

In 2010, as a novice to condors, I began to volunteer with Pinnacles’ Condor Recovery Program. Since then I have been amazed, inspired, and challenged by the unceasing dedication of those working to help the condor sustain success in its wild habitat. As my awareness of the condor’s challenges has grown, I have witnessed challenges to this support program also emerge.

In 2013 Pinnacles National Monument became Pinnacles National Park. This brought national attention to Pinnacles and attracted a massive influx of new park visitors. Seeing the strains and challenges associated with this growth in park attendance, I extended my personal in-park efforts and began to raise funds for the Pinnacles Condor Recovery program. This led to my co-founding the Pinnacles Condor Fund in 2013. Today, this special interest fund is administered by the park’s friend’s group Pinnacles Partnership (PiPa).

Condors are a huge part of my life. I find myself at Pinnacles National Park about one week every month and I am also engaged from my home in Richmond, California. My indoor tasks encompass condor-observation data entry and related paperwork, Pinnacles staff meetings and PiPa board and committee meetings, and my continuing personal study and learning.

My much-preferred outdoor activities include solitary and group hikes to observe and record our flock (under the direction and instruction of the Pinnacles Condor Program staff), helping track condors from the air with volunteer pilots who assist in observation and recovery efforts, and frequently leading fundraising treks with park visitors and specialists to condor overlook sites. I often co-lead fundraiser hikes with Golden Gate Bird Alliance instructor Rusty Scalf.

In order to perform my volunteer responsibilities, I have been carefully instructed and guided by Pinnacles staff to use specialized equipment, prepare data for entry into various databases, support research projects and questions, and observe established Condor-related protocols and practices. Being a volunteer in the Condor Recovery Program takes training, commitment, stamina, and, many times, simple good humor. In return, I receive immeasurable rewards of all kinds including friendships with birds and people I deeply respect.

A Condor Tracker’s Daily Diary

Since I began spending time regularly in Pinnacles and observing the flock, I have kept a journal of my daily activities. As these following entries reveal, my experiences run the gamut from mundane to amazing – with the amazing ones bringing me awe and joy.

These excerpts from my personal daily journals provide a sense of a condor crew volunteer’s first year on the job – and the relationship we volunteers have with the flock. The comments in italics provide additional information about the journal entry and its context.

As these entries indicate, 2010 was a life-changing year for me.

July 12, 2010 – my first year as a volunteer – a summer hike

Hiked to Scout Peak this AM to radio track the condor flock. Not many birds to start, but did observe one CACO (maybe 3 – too far to positively ID the other 2) soaring in the distance. Never able to get a tag visual, but signal indicates #313.

Note: CACO means California Condor

Hot today! I should get a thermometer so I can quantify the misery.

Had contact with 8 or 10 birds today – and 8 humans. Saw a gopher snake on the way up this morning – first Pinnacles snake while hiking. Also saw a magnificent Cal. Whiptail lizard on the way down. Maybe 8”, nose to tail.

July 13, 2010 – observing rookie and veteran birds in the release pen

Hiked to the facility today to observe the rookies – 2 from Portland & 2 from Boise + 2 vets in the flight pen. The rookies are scheduled to be released in September. I will certainly be here for that.

Spending an entire day in a darkened room, looking at condors through one-way glass may seem boring. But watching these highly social birds interact is anything but boring. It is good to see the rookies getting along with the vets.

Note: rookies are young, captive bred condors. The Oregon Zoo in Portland and the World Center for Birds of Prey in Boise, Idaho, are captive breeding facilities. Vets are older mentor condors.

Juveniles from these captive breeding programs are placed into a pen by Pinnacles staff when they arrive. Here, they join other birds waiting to be released to the wild and older veteran condors who help the rookies become familiar with the location and the flock. An observation building adjacent to the pen enables staff and volunteers to observe birds.

The new arrivals may stay in the release pen for 8-12 weeks and are observed constantly. Wild condors visit the pen frequently to socialize with rookies but wild birds cannot enter the pen. The rookies are carefully released, usually one at a time, and continuously monitored thereafter.

The calf carcass below me is an added dimension. The CACOs are just picking at it, though – not really feeding.

About noon a wild condor (#421) arrived to check out the scene in the flight pen. He stayed for about and hour – interacting with the rookies primarily & went on his way.

At 4:00 I started the hike back down to the turn-around to meet Jennie. She is picking up me & Danielle who spent the day @ One Pine

I haven’t been to One Pine yet. I could see it across the canyon on my way to the facility. About the same elevation as the facility, but the trail is straight up – no switchbacks – which is why I haven’t been. Sooner or later I’ll get there.

Note: Jennie Jones was an intern on the Condor crew; she is now a crew leader. Danielle is another intern. One Pine is a condor observation point within Pinnacles National Park. At the time, I was still recovering from a total knee replacement about a year earlier.

August 12, 2010 – encountering park visitors on summer hikes

High Peaks (Scout Peak) today. First visitor was an elderly woman from Paso Robles. Very fit & spry. She said she had volunteered for a week with the Condor Program @ Grand Canyon.

Talking to interesting people is one of the things I enjoy most about tracking up here, as well as helping to educate people about the Condor Program. Many of the hikers are local people who have at least some knowledge of the program. Others have no idea it even exists. Monday there was a couple from Syracuse, NY who had no idea, but were thrilled to hear about it. Not long after they left, 421 flew by. Too bad they missed it.

A couple just came up from the east side – the man had a small cooler over his shoulder. They studied the trail map briefly & headed down the west side. One wonders if they have a clue what they’re doing. They’ll have a long slog – in PM heat to get back to Bear Gulch. Should I have said something? I think he is dragging her into a rough day.

Another couple just arrived from Bear Gulch intending to do a loop via the Steep & Narrow/Condor Gulch trails. They had one small bottle of Crystal Geyser after drinking 3 bottles on the way up. I advised them against continuing. They had no idea what they were in for (thought they were at the Steep & Narrow/Condor Gulch junction) & were very grateful for my advice & turned back.

It’s not super hot today (95 -100 degrees), but hot enough to get in trouble. I really do need to get a thermometer to carry.

Note: in the ensuing years, I’ve had occasion to turn many hikers around. It amazes me how people ignore the prominent signs about carrying sufficient water.

A group of 7 people just came through who didn’t speak much English. I did manage to communicate what I was doing, which they thought was wonderful, and thanked me profusely. They headed down toward the west side, but stopped & talked briefly among themselves. Then one of the came back, handed me a chocolate pie – a Moon Pie sort of cookie & and piece of hard candy, thanked me profusely again, explaining that they had plenty & then left. NICE!

November 16, 2010 – release of rookie 547

This morning, I’m below the observation facility, monitoring the potential release of the remaining rookies. 547 is now in the trap, with the roof open, so freedom is hers when she chooses.

Note: The trap is a special part of the release pen that can be opened by staff to give the rookie a way to exit the pen.

When rookies are released they are followed closely for a few days to make sure they are perching in trees at night – not on the ground. These CACOs have very limited flight skills since they’ve only been able to flap around a flight pen for the previous 1 ½ years. If they roost on the ground at night they are vulnerable to predation by mountain lions, bobcats or coyotes.

9:25 AM – 547 chose freedom! I’m watching the 1st flight of a young condor! This is exciting and wonderful. Jennie is @ the facility & Joseph is @ One Pine. We’re hopeful that the other bird will enter the trap now.

Note: Joseph is another volunteer.

For the last hour or so, 547 has been on the ground, directly across the road from the One Pine trailhead & roughly level with it. She’s currently sunning herself (wings stretched out) & shows no signs of wanting to leave. If she’s still there when Jennie gets down from the facility, we’ll roust her out.

What a glorious day! Little wisps of clouds, 75 degrees, and lots of CACOs soaring. I’m a lucky man! I could (& intend) to do this forever!

Note: as my friend Sean (another volunteer) says, “I can’t believe they let me do this for free!”

547 just lifted off and flew up the little side canyon below the blind. Out of visual contact now & I can’t get a signal on her. Joseph, at One Pine, has a steady signal, so she’s gone to ground again, up the side canyon.

About 3:00, Jennie came down & we tried to get a fix on 547 – turns out my telemetry receiver had been mis-programmed, preventing me from getting a signal. Jennie is receiving signals from the other side of the canyon from where I thought 547 had to be.

We drove a short distance & took signals again. We got strong signals & I soon spotted her in a tree near the top of the hill.

This is great! We were afraid she’d go to ground again where she’d be vulnerable to predators. Finding her in a tree is the best possible outcome. She’s displaying very “condor-ly” instincts.

We stayed with her until nearly dark & then headed in – satisfied that she’s free & safe. Maybe tomorrow we can spring the last rookie.

Thoughts about Condors and the Recovery Efforts

From my five+ years of condor-recovery volunteering, I have been deeply impressed with the work of the recovery program’s complex set of alliances – from federal agencies led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Pinnacles National Park to state and local government groups, private conservation organizations, and the tireless work of individuals.

Many people and groups with very different interests, skills, responsibilities, budgets and resources give generously, doing what they can to support our common objective: to restore the California Condor to the wild. Finding alignment of goals and tasks across this vast landscape of participants is in itself inspiring. We can – when we so choose – accomplish amazing results that improve and inspire the world.

We all hope that this alliance goes out of business because we are no longer needed. But that seems unlikely in the near term. The California Condor is still in great need of support from the government, the general public, and trained volunteers able to support professional staffs and programs.

The operational challenges faced by this program relate mostly to ever-increasing expenses of a growing wild flock (the good news!) paired with the government’s program and park funding that needs to be stretched further than ever.

The daily operations of the Condor Recovery Project are costly, labor intensive, complex to plan, execute, and track, and sometimes disheartening when we have setbacks. Emergencies may not have been budgeted for in advance. For example, condors carry communications technology that is expensive, gets damaged and becomes outdated. Tracking relies on subscriptions to satellite services, radio telemetry equipment, planes that need fuel and maintenance, and software systems that need maintenance and upgrading. Additionally, specialized care for condors themselves is resource- and budget-intensive. We are still needed.

The Pinnacles Condor Fund, a source of private donated funds, makes money available to the Pinnacles’ California Condor Recovery Program for special circumstances and emergencies, as far as it is able. Pinnacles Condor Fund and its umbrella organization Pinnacles Partnership conduct ongoing fundraising programs for this purpose, as well as for continuing condor awareness and education outreach.

I invite you to participate in our upcoming Fall 2015 PINNACLES CONDOR EXPERIENCE – free lectures at REI locations in eleven cities around the Bay Area, and fee-based fundraising hikes in Pinnacles National Park in October, November, and December. Information and registration information is on this flyer and at the Pinnacles Partnership website. Mark the date and register for the REI lecture near you – starting August 11th.

Most of all, be sure to come to Pinnacles and experience for yourself all of its natural majesty. Don’t forget to look up into the skies – is it a crow? Is it a Turkey Vulture? No, it’s a California Condor!!

… an icon of America gracing the skies with its majesty, thanks to the efforts of people and programs dedicated to its recovery.

—————————————————

Richard Neidhardt is Chair of the Pinnacles Condor Fund and a volunteer at Pinnacles National Park. He has co-led trips to Pinnacles for Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s Birdathon. Richard can be reached at rfneid@gmail.com.

Richard grew up on a lake in South Carolina, obsessed with everything that crawled, hopped, swam or flew. He spent 40 years in the construction industry as an estimator/project manager in California and elsewhere. In 2009 he retired and shortly thereafter began to volunteer with the California Condor Recovery Program at Pinnacles. In 2013 Richard and Jeff Robinson co-founded the Pinnacles Condor Fund to raise supplemental money for the park’s condor protection operations.