Birding While Black

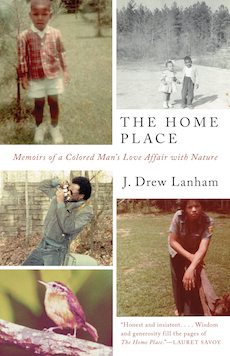

Editor’s Note: Some people go birding to escape from the stresses of daily life. For birders of color, those stresses often continue into the field. This timely and compelling essay is excerpted with permission from J. Drew Lanham’s new book, THE HOME PLACE: MEMOIRS OF A COLORED MAN’S LOVE AFFAIR WITH NATURE.

By J. Drew Lanham

It’s only 9:06 a.m. and I think I might get hanged today.

* * * *

The job I volunteered for was to record every bird I could see or hear in a three-minute interval. I am supposed to do that fifty times. Look, listen, and list for three minutes. Get in the car. Drive a half mile. Stop. Get out. Look, listen, and list again. It’s a routine thousands of volunteers have followed during springs and summers all across North America since 1966. The data is critical for ornithologists to understand how breeding birds are faring across the continent.

Up until now the going has been fun and easy, more leisurely than almost any “work” anyone could imagine. But here I am, on stop number thirty-two of the Laurel Falls (Tennessee) Breeding Bird Survey route: a large black man in one of the whitest places in the state, sitting on the side of the road with binoculars pointed toward a house with the Confederate flag proudly displayed. Rumbling trucks passing by, a honking horn or two, and curious double takes are infrequent but still distract me from the task at hand. Maybe there’s some special posthumous award given for dying in the line of duty on a Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) route—perhaps a roadside plaque honoring my bird-censusing skills.

My mind plays horrific scenes of an old black-and-white photograph I’ve seen before—gleeful throngs at a lynching party. Pale faces glow grimly in evil light. A little girl smiles broadly. The pendulant, black-skinned guest of dishonor swings anonymously, grotesquely, lifelessly. I can hear Billie Holiday’s voice.

The mountain morning, which started out cool, is rapidly heating into the June swoon. I grip the clipboard tighter with sweaty hands, ignoring as best I can the stars and bars flapping menacingly in the yard across the road. The next three minutes will seem much longer.

On mornings like this I sometimes question why I choose to do such things. Was I crazy to take this route, up here, so far away from anything? What if someone in that house is not so keen on having a black man out here, maybe checking out things—or people—he shouldn’t be? I’ve heard that some mountain folks don’t like nosy outsiders poking around. Yet here I am, a black man birding.

* * * *

Over the years I’ve listed hundreds of species in hundreds of places, from coast to coast and abroad, too. I’ve seen a shit-ton of birds from sea level to alpine tundra. But as a black man in America I’ve grown up with a profile. Society at large has certain boxes I’m supposed to fit into, and most of the labels on those boxes aren’t good. Birders have a profile as well, a much more positively perceived one. Being a birder in the United States means that you’re probably a middle-aged, middle-class, well-educated white man. While most of the labels apply to me, I am a black man and therefore a birding anomaly. The chances of seeing someone who looks like me while on the trail are only slightly greater than those of sighting an ivory-billed woodpecker. In my lifetime I’ve encountered fewer than ten black birders. We’re true rarities in our own right.

* * * *

For three years I’ve been responsible for this route, the only mountain BBS in the state. The scenery seemed worth the work. For good portions of the route the Blue Ridge Mountains crest the horizon. Birding in and out of open land and forests, with field sparrows bouncing songs off the broom sedge at one stop and hooded warblers blasting from a laurel-cloaked cove at the next, I sometimes have to pinch myself. Stop number twenty-four, beside an old apple orchard, is spectacular. Warbling blue grosbeaks, buzzing prairie warblers, and chattering yellow-breasted chats usually make the three minutes go by quickly. Earlier, when a lone bobwhite called from somewhere in the tangle of weeds and brush, I’d taken it as good omen for the day.

“Okay, 9:04. I need to start. A wood thrush—good, that’s the first one for today. Summer tanager—no, scarlet tanager—two of ’em. American crows—sounds like maybe three of those . . .”

In the midst of ticking off species the thoughts begin to filter through my head again. Maybe these folks are the “heritage, not hate” type. I don’t see any black lawn jockeys, wheelless cars hoisted up on cinder blocks, or rabid pit bulls in the yard. The only irritant beyond the flag is a persistently yapping Chihuahua, announcing my presence to anyone within earshot.

“OK. Was that a goldfinch singing from the top of that poplar? Definitely goldfinch.” A quick glance at my watch. I still have a full two minutes to go.

A yellow-billed cuckoo croaks from somewhere in the neighboring woodlot and I add it to the list. But I don’t catch the next bird’s call because I’m distracted. “Is somebody coming?” I imagine a scraggly haired hillbilly who is going to require things I’m unwilling to give. Past incidents don’t fade quickly from memory, especially when the threats of danger were real, raising a sour-slick tang of bile in the back of my throat.

* * * *

On one of my first jobs with the Department of Natural Resources, I thought my color would cost me my life. My supervisor, Kate, and I went out to deploy live traps for bats and small mammals up in the remote Jocassee Gorges of South Carolina, a maze of rhododendron-choked mountain coves, small streams, and pine-studded ridges. It’s as close to wilderness as there is in the portion of the Upstate folks used to call the “Dark Corner.”

I’d heard that people in the mountains didn’t like strangers of any color. I was a strange stranger, and maybe not the person locals would think should be working with a white woman. Kate was a super-observant naturalist, who noticed the slightest nuances in tooth pattern or fur color—but was, I think, oblivious to the threat I perceived.

Riding on an old logging road just wide enough for one vehicle, we met another truck. The rusting, dented pickup’s cab was full of three men. One of the vehicles would have to give way to the other on the narrow track, and so we pulled over. Kate and I each threw up a hand, offering the customary southern pickup-passerby wave. Their responses seemed halfhearted. Hardly a finger went up. Instead the men stared, heads slowly swiveling. Their looks bored through the windshield and wrapped themselves around my throat. The six eyes seemed to be making decisions I didn’t want to be a part of.

I turned around as they rumbled by. Their brake lights suddenly flashed and the backup lights came on. The truck made a three-point turn for the only reason I could imagine: they’d decided that they didn’t want us back there. My stomach knotted. I wondered how long it would take the authorities to recover our decomposing corpses from the rhododendron hells where these hillbillies would dump us after they did whatever the fuck it was they wanted to do. Kate nonchalantly wondered aloud at the trailing truck’s intent but seemed more concerned that they’d maybe screwed with the pitfall traps we were going to check than about the prospect of impending assault.

I was on an edge that I’d only experienced in very bad dreams. The going was slow and the men followed us by a hundred yards or so. They kept pace, turn for turn. The knot in my belly tightened. We were on a dead-end road with no escape. We were unarmed. Without question the men in the truck would have guns and knives—probably a rope, too. For the first time in my newborn wildlife career I was questioning whether following my outdoor passion was truly worth it.

I’m not sure whether I prayed. Back then God was still an option in such circumstances. But whatever wish I threw out of the pickup window was granted. The trio stopped and turned around just as suddenly as they’d done in the first place. Kate drove on deeper into the gorge’s maw and we worked into the evening, until darkness drove us from the woods. We didn’t catch anything that day. I would’ve normally checked each trap with a Christmas-like anticipation, hoping some small critter—a smoky shrew, golden mouse, or red salamander—might be at the bottom of one of the five-gallon bucket traps.

That day, though, I couldn’t have cared less. I worried over our exit. I was sure the men were just biding their time, lying in wait for us to come back out the only way we could. I fully expected to see them parked around every hairpin turn. I didn’t relax until we hit the asphalt road that would take us home with speed. Kate told me later that she suspected the men in the truck thought we were law enforcement, maybe looking for marijuana patches or moonshine stills hidden in the woods.

In remote places fear has always accompanied binoculars, scopes, and field guides as baggage. A few years later, during my doctoral field research, three raggedy, red spray-painted Ks appeared on a Forest Service gate leading to one of my study sites. When I saw the “welcome” sign, many of the old feelings came back. I instinctively looked over my shoulder to see if anyone was watching. And I didn’t visit the point again. My safety compromised, I found another place to do the science. I’d had to do this a couple of years earlier, too, when a white supremacist group “organized” in the mountains of western North Carolina, near the places I was supposed to do a research project. They’d made the national news in stories that showed them worshipping Hitler and shooting at targets that looked like Martin Luther King Jr. Someone at the university joked about my degree being awarded posthumously. So though the proposal had been written and the project was well on its way to being funded—and as potentially groundbreaking the research on rose-breasted grosbeaks, golden-winged warblers, and forest management in the Southern Appalachians might be—I had abandoned the whole thing.

These decisions put doubts about my dedication to the field in my head. After all, I was in wildlife biology, a profession where work in remote places is often an expectation. Any credibility I was trying to build would be shattered if I showed hesitation in venturing out beyond some negro-safe zone of comfort. And so I mostly swallowed the fear, adjusted when I had to, and moved on.

I’m not alone, though. I have friends—black friends—who’ve also experienced the lingering looks, the stares of distaste. They’ve endured comments about their color flung within earshot. I look at maps through this lens—at the places where tolerance seems to thrive, and where hate and racism seem to fester—and think about where I want to be. Mostly those places jibe with my desire to be in the wild but sometimes they don’t.

The wild things and places belong to all of us. So while I can’t fix the bigger problems of race in the United States—can’t suggest a means by which I, and others like me, will always feel safe—I can prescribe a solution in my own small corner. Get more people of color “out there.” Turn oddities into commonplace. The presence of more black birders, wildlife biologists, hunters, hikers, and fisherfolk will say to others that we, too, appreciate the warble of a summer tanager, the incredible instincts of a whitetail buck, and the sound of wind in the tall pines. Our responsibility is to pass something on to those coming after. As young people of color reconnect with what so many of their ancestors knew—that our connections to the land run deep, like the taproots of mighty oaks; that the land renews and sustains us—maybe things will begin to change.

I’m hoping that soon a black birder won’t be a rare sighting. I’m hoping that at some point I’ll see color sprinkled throughout a birding-festival crowd. I’m hoping for the day when young hotshot birders just happen to be black like me. These hopes brighten the darkness of past experiences. The present does, too. What I’ve learned from all the years of looking for birds in far-flung places and expecting the worst from people is that my assumptions are more times than not unfounded. These nature-seeking souls are mostly kindred spirits, out to find not just birds but solace. A catalog of friends—most of them white—have inspired, guided, and sometimes even nurtured my passion for birds and nature. As we gaze together, everything that’s different about us disappears into the plumages of the creatures we see beyond our binoculars. There is power in the shared pursuit of feathered things.

* * * *

Forty-five more seconds and I will be done. An ovenbird singing over there. A northern cardinal chipping. And human eyes on me. I can feel them watching. This last minute is taking forever. The little mutt is barking like it’s rabid. I don’t hear or see any birds in the last thirty seconds because I am watching the clock tick down. Time’s up! I collect my fears and drive the next half mile, on to stop number thirty-three.

J. Drew Lanham is a native of Edgefield, South Carolina, and an Alumni Distinguished Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Master Teacher at Clemson University. Lanham is a birder, naturalist, and hunter-conservationist who has published essays and poetry in publications including Orion, Flycatcher, and Wilderness Magazine and in several anthologies including The Colors of Nature, State of the Heart, Bartram’s Living Legacy, and Carolina Writers at Home, among others. He is the author of The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, published in September 2016 by Milkweed Editions. Click here to order a copy from Milkweed, or ask for it at your neighborhood bookstore.