A century of birds at UC Berkeley

By Ilana DeBare

As both a birder and a Cal alum, I perked up when this press release from U.C. Berkeley came across my desk:

A graduate student recently completed a six-month count of birds on the Cal campus — and found that the number of species today is actually higher than a century ago.

Allison Shultz identified 48 species in an 84-acre portion of the 178-acre central campus. That’s more than the 44 species recorded with similar methodology in 1913-18, and more than the 46 recorded in 1938-39 by none other than a young, not-yet-famous Charles Sibley.

“The presumption going in was that we would see a steady decline in the number of species because the campus, like any urban environment, has been heavily modified, with more buildings and 15 times more students,” said Rauri Bowie, a Cal biology professor who co-authored the study with Shultz. “But despite everything that has happened on campus in the past century, we find absolutely no evidence for that.”

Still, though the total number of species stayed steady, the kinds of birds changed dramatically with changes in the campus landscape.

In 1913, the oak woodlands and shrubby chaparral of Cal were filled with Song Sparrows, White-Crowned Sparrows and Golden-Crowned Sparrows. Wrentits lived in the brush and Western Meadowlarks in the grasslands.

Today, some oaks remain but the tall grasses and chaparral have given way to lawns and ornamental shrubs. And common species include Lesser Goldfinch, Nutall’s Woodpecker, and the Chestnut-Backed Chickadee.

Shultz noted an increase in species that typically do well in human habitats: crows, ravens, hawks, Ring-Billed Gulls and Mourning Doves.

“We found evidence that if you still have a lot of open space, as in the suburbs or on campus, you tend to get community turnover,” Bowie said. “Very sensitive species disappear, but other species come in to fill similar functional roles. You get different seed eaters and different fruit eaters, for example, with no decrease in net diversity.”

Shultz and Bowie published their study in The Condor journal, the same place that Sibley published the survey he did as a Cal grad student in 1938-39.

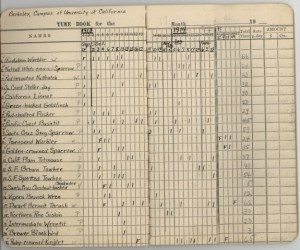

Their work was unusual in that few researchers from a century ago left notes detailed enough to allow today’s scientists to replicate their work and make comparisons. The 1913 survey was influenced by zoologist Joseph Grinnell, whose method of precise observation and annotation became the basis of much of today’s field biology.

Shultz spent three hours per day for 60 days surveying campus birds on the same routes used 100 years ago. You can read more details about her survey in the press release.

Of course, even with all Shultz’s work, she neglected to answer one question that cried out to the Cal alum part of me.

I guess we’ll have to leave that to the next generation of ornithology students:

Does Cal have more bird species than Stanford?