A century since the last Passenger Pigeon

By Ilana DeBare

This Monday September 1st will mark the 100th anniversary of the death in captivity of the last Passenger Pigeon.

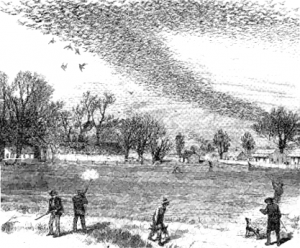

Several months ago, I read Richard Rhodes’ fascinating biography of John James Audubon and was struck by Audubon’s description of the arrival and slaughter of a massive Passenger Pigeon flock in the midwest around 1816:

“The noise which they made, though yet distant, reminded me of a hard gale at sea…. As the birds arrived and passed over me, I felt a current of air that surprised me. Thousands were soon knocked down by the pole-men. The birds continued to pour in…. The Pigeons, arriving by thousands, alighted everywhere, one above another, until solid masses as large as hogsheads were formed on the branches all around. Here and there the perches gave way under the weight with a crash, and, falling to the ground, destroyed hundreds of the birds beneath, forcing down the dense groups with which every stick was loaded. It was a scene of uproar and confusion. I found it quite useless to speak, or even to shout to those persons who were nearest to me. Even the reports of the guns were seldom heard, and I was made aware of the firing only by seeing the shooters reloading….

The Pigeons were constantly coming, and it was past midnight before I perceived a decrease in the number of those that arrived. The uproar continued the whole night…. Towards the approach of the day, the noise in some measure [having] subsided, long before objects were distinguishable, the Pigeons began to move off… and at sunrise all that were able to fly had disappeared. The howlings of the wolves now reached our ears, and the foxes, lynxes, cougars, bears..

It was then that the authors of all this devastation began their entry amongst the dead, the dying and the mangled. The pigeons were picked up and piled in heaps, until each had as many as he could possibly dispose of, when the hogs were let loose to feed on the remainder.”

Such massive flocks were not unusual: The largest known nesting site was documented in 1871 in Wisconsin with 136 million birds covering 850 square miles.

Their large flocks and communal behavior made the pigeons easy prey for hunters. Faced with massive commercial hunting and loss of habitat, their numbers dwindled. Then, a century ago, they were gone.

The Passenger Pigeon’s story is particularly cautionary for us these days because, with climate change, we may be on the verge of witnessing a tidal wave of similar extinctions.

In September — by coincidence about a week after the sad anniversary of the Passenger Pigeon’s loss — National Audubon will release a very comprehensive scientific report on North American birds and climate change that has been years in preparation.

Which species will face significant habitat loss? Which ones are likely to adapt and survive? Which are at risk of extinction?

We’ll share the news here with you as soon as we get it, along with steps we can take to protect the Northern California species most at risk due to climate change.

Meanwhile, please consider doing one small thing on Monday to mark the death of Martha, that last lone pigeon in the Cincinnati Zoo.

Talk to one non-birder friend about why you care about preserving species…

Write a letter to one elected official in Washington…

Take a young person out to a park and help them spot an egret in the marsh…

Post a Passenger Pigeon image on your Facebook page, and ask your friends to share it…

Replace the energy-hogging incandescent bulbs in your house with LEDs or compact fluorescents, and think of Martha while you do it….

In 2114, will our grandchildren or great-grandchildren be writing blog posts commemorating the anniversary of the death of the last Tricolored Blackbird? Ashy Storm-Petrel? Yellow-billed Cuckoo? Burrowing Owl? Snowy Plover?

Or might there be so many losses that they won’t even know where to start?