Birding the Bay Islands: Mare Island Shoreline & Beyond

By Helen J. Doyle and Evan Weissman

Maybe the birds knew Valentine’s Day was just two days away. Love was in the air, literally. Soon after we left the Mare Island San Pablo Bay Trail parking lot, we were stopped in our tracks by two pairs of Northern Harriers in full airborne courtship display, swooping around each other, showing off their legs and feet, and vocalizing back and forth.

Northern Harriers were also using the sky for stunning displays of romance. Both species are year-round Bay Area residents, feeding on small mammals and birds that also thrive in this marshy, grassland habitat. A thrilling start to birding on Mare Island.

First though, is Mare Island really an island? Its Spanish names suggest it was at one time – Isla de la Plana (Flat Island) around 1775 and later, around 1834, Isla de la Yegua (Mare Island), renamed by Mariano Guadeloupe Vallejo in honor of his white mare who safely swam ashore here after a boat capsized in the Bay in 1835. Soon after that, in 1854, the US Navy opened its first west coast shipyard here. The Navy and shipbuilding dominated Mare Island for almost 150 years, until 1996, changing its landscape to better suit these industrial purposes. Now Mare Island is a peninsula, bordered by the Napa River and the San Pablo Bay, but it’s easy to imagine that the Napa River once flowed more freely into the Bay, creating wetlands dotted with islands like Mare Island. Today those wetlands make up the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Mare Island is not technically part of this refuge, but its wetlands are also being restored as the decades-long decommissioning of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard continues.

To get here, we ferried from San Francisco to Vallejo with our bikes and rode over to Mare Island via the scrappy but solid Mare Island Causeway Bridge, built in 1934. We sited a few morning birds along the Vallejo marina and shoreline park before meeting fellow-birders Jon Altemus and Marilyn Nasatir at the San Pablo Bay Trail parking lot. Despite a reputation for single-mindedness, birders are generous about sharing knowledge and teaching others. We laughed about Marilyn’s story of becoming hooked by birds over three decades ago. After a bird walk in Golden Gate Park, for which she had opera glasses but no binoculars, she thought she’d seen just three types of birds. Her more experienced friend confirmed they’d seen 43 species, and Marilyn was hooked (and soon invested in binoculars!).

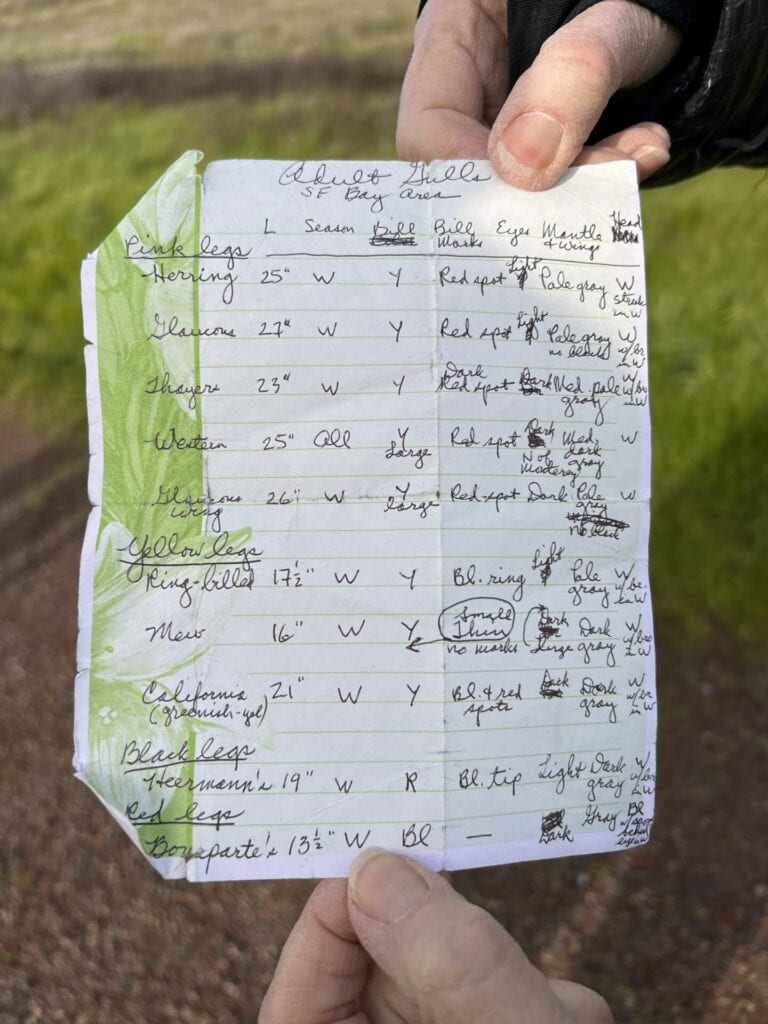

She now carries a carefully folded, handwritten gull “cheat sheet” charting distinct features of 10 gull species. Gull identification is notoriously tough, so Evan and I eagerly took pictures of her key.

The grassland and shrubland habitat bordering the trail was likely drained and filled in by the military and is now transitioning back to a more natural state. We saw a handful of sparrows and a few finches, phoebes and meadowlarks, but this area was quieter than we’d expected. We wondered about the barbed wire fence separating the trail from hazardous areas, another legacy of the island’s military presence. Still, given the paucity of trees, we were pleased that the fence provided perches for flocks of Red-Winged Blackbirds and Western Meadowlarks, along with a few White-Tailed Kites resting from their aerial show.

Closer to the shoreline, the habitat was more tidally influenced, dominated by native pickleweed. Flocks of Marbled Godwits, Long-billed Curlews, and Willets swooped down in their choreographed dance of murmuration. A hundred or so Canvasbacks and Northern Pintails drifted just past the shoreline along the edge of the bay. Part of the Pacific Flyway, Mare Island and nearby wetlands provide food and shelter for these shorebirds, ducks, and other migrants to overwinter. An osprey perched on a snag, slowly eating its prey. A raft of White Pelicans floated out on the Bay.

Given the distance and poor visibility, we each did several doubletakes to be sure they were not simply a discarded raft. Small inland ponds, likely created by our wet winter, supported a diversity of waterbirds: Buffleheads, Ruddy Ducks, American Coots, Mallards, and others. In the final pond we passed, there were seven huge Mute Swans, an introduced species that is somehow both graceful and grotesque.

We identified 45 species on our leisurely two-mile loop along the San Pablo Bay Trail. As we circled back to the parking lot, a kettle of Common Ravens, Red-tailed Hawks, and Turkey Vultures spiraled in an updraft above us. We’d come mainly to explore the shoreline, yet the start and end of this walk reminded us that the sky is often the most exciting habitat to watch.

“The vision of the Harriers and Kites displaying and vocalizing will stay with me for a long time,” Jon Altemus said after our trip together.

Leaving the shoreline, and Marlyn and Jon, behind, we biked toward the tip of the island and then up the Mare Island Shoreline Heritage Preserve hill to the Spirit Ship sculpture, near the island’s highest point. From this view we could fully appreciate the extent of the shoreline habitat we’d just visited. Seeing the full extent of the San Pablo Bay, we could imagine the wetlands at the mouth of the Napa River that once separated Mare Island from the mainland.

The woodland and chaparral habitat on the hill hosts a very different population of birds than we’d seen on the shoreline. We covered 1.5 miles and identified 26 bird species, well over half of which we hadn’t come across on the San Pablo Bay Trail.

We couldn’t know what this habitat was like when it was solely inhabited by people of the Patwin tribe. Now we saw a mix of California native and introduced plants–Coast Live Oak, Monterey Pine, Toyon, Eucalyptus, Acacia, and Palms from who knows where. In a stand of several impressively large eucalyptus trees, we heard a wild chorus of American Robins (the quintessential sound of spring for many people) and caught glimpses of Yellow-Rumped Warblers. We began to leave but stopped when we spotted a flock of Cedar Waxwings, their striking yellow and peach-tan bodies, black eye masks, and red and yellow feather tips somehow blending in perfect camouflage with the Eucalyptus leaves and bark. Although primarily fruit eaters, this flock was feeding on insects. Watching these beautiful birds flick out to catch a bug and land safely back on their branch, we lost track of time and had to ride full speed back to Vallejo to catch our ferry home.

As the ferry left Vallejo, we saw at least a half dozen Great Blue Heron nests in trees along the Mare Island shoreline, even a double decker one on an old industrial pole! Most other remnant metal poles had the makings of Osprey nests, some occupied. Further out, a flock of hundreds of Surf Scoters, another winter visitor to the Bay, floated calmly on the water. We braved the chill wind as long as we could before retreating inside, marveling over the variety of birds we had seen and the marked differences between the different habitats, even on this one small island.

Helen J. Doyle is a California Naturalist and educator dedicated to the environment, public education, and equity and justice. A biologist by training, she shares her love of nature as a docent and writer. She volunteers with several Bay Area organizations, such as Año Nuevo State Park, the Gardens of Golden Gate Park, and the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, and serves on the advisory council of Nature in the City, a San Francisco nonprofit that connects people to nature. (Helen on LinkedIn)

Evan Weissman is an interpreter of natural and cultural history, and of the connections between the two. He currently works at Angel Island State Park in the San Francisco Bay, and volunteers with Año Nuevo State Park, Golden Gate Bird Alliance, the Marin County Breeding Bird Atlas, and the Morro Bay Bird Festival. Evan is a certified California Naturalist and Climate Steward. (Evan on LinkedIn)