A field guide to my first field guide

By Allen Fish

Chandler Robbins died last month. He would have been 100 years old this July 17th. Never as famous as Roger Tory Peterson or David Sibley, Chandler Robbins made some of the most important contributions to bird research and conservation in the 20th century.

He conducted some of the earliest research on DDT, contributing to Rachel Carson’s crusade; he pioneered the U.S. Breeding Bird Survey, a system of point counts designed to capture data on bird population changes across the continent; and he banded what is believed to be the world’s oldest, still-living bird, an individual Laysan Albatross on Midway Island in 1956. These are just a few stepping stones across the arc of Robbins’ amazing career.

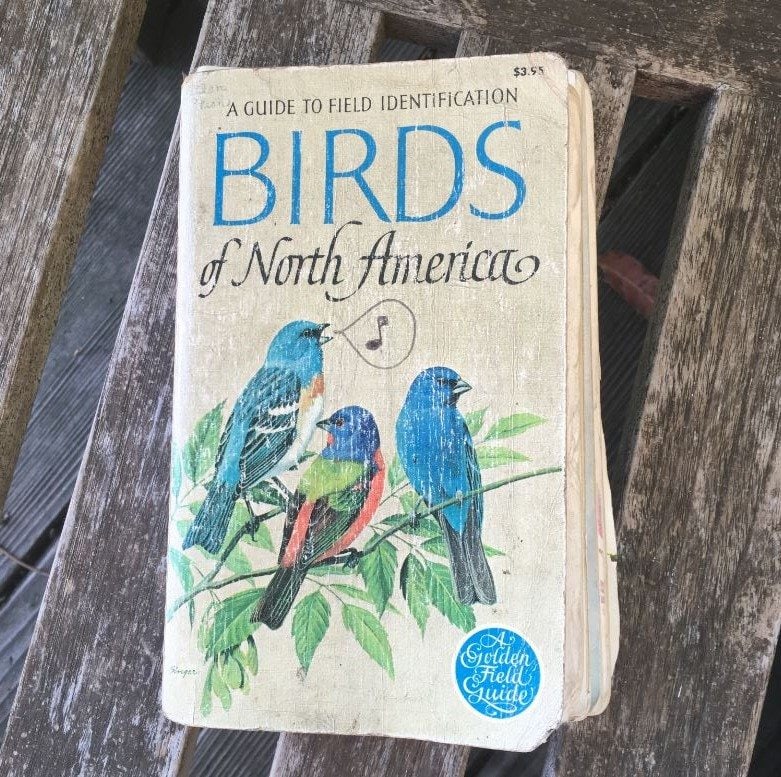

Robbins was also the author of the Golden Guide to North American Birds. First published in 1966, just a few years on the heels of Peterson’s Western Guide, the Robbins Guide corrected a few of the Peterson mistakes. Robbins put bird pictures, descriptions, and maps all on one open double-page. No flipping to the back to see what the range was. And for many passerines, there were sonograms right there as well. And everything in color.

I got my Robbins Guide not long after, a Christmas present from a grandparent I think, as instructed by my parents with a shrug. “He likes birds.” It was 1968. I was seven years old. The political world was swirling in change but I didn’t know anything about that. I liked birds.

Fifty years later, I pull Robbins from my book case and put it next to my laptop. It falls open flat into three separate pieces. This is in spite of at least two patch jobs I did back in the 1970s. One I did with black electrical tape from dad’s electrical fix-it box. The other was with clear contact paper from mom’s craft drawer. Fortunately today, the heavy vinyl-ish soft-cover is still mostly intact and so holds the sections a bit like an ancient manila folder.

On the cover, with its three species of male buntings, faint in the upper left corner is my name in a rolling cursive pen typical of a fifth grader. It’s likely the first book I wrote my name in. In a moment of pre-teen comic brilliance, after learning the basics of reading music (learned many times, never took), I made a talking balloon from the Lazuli Bunting’s open beak and put a quarter note in it. Tweet. Little did I know, twenty years on, I would lie back on a grassy hill in the Marin Headlands and listen to two male Lazulis hurl songs at one another. Tweet indeed.

On the inside back cover, I wrote a curt instruction: “Return to,” with my childhood address next to it – “575 Sequoia Ave./Redwood City, Calif./94061.” This insurance policy was never required; I lost many wallets, keys, etc., over the years, but never my Robbins. On the outside back cover, left unmarked by the publisher, I later penned my college contact info — “1311 L Street/Davis, CA/916-756-9601” — which means that as late as 1980 I was still using Robbins as my go-to field guide. Also on the back was the faintest attempt at writing the names of several avian families. (Weird logic: if I write them on my field guide, I will memorize them.)

Hilariously, the only legible family name today was Ploceidae, one of the few non-native families I had to learn (European House Sparrow). I made this effort when I took my first Ornithology course at U.C. Davis as a sophomore in 1982. Professor Robert L. Rudd, also a pal of Rachel Carson, forced us to memorize all the orders and families of California’s birds. A quarter century later, I imposed this so-satisfying torture on my undergrads when I taught Raptor Biology at UCD. Obscurity begets obscurity.

I don’t shrink from writing in books today, considering it my responsibility to improve on them and to remember favorite parts, and Robbins was no exception when I was still pretty young. I discovered one day while poring through its paintings that the index did double-duty as a check-list of bird species. All the proper names had little boxes adjacent so that one could check the birds one had seen. What a great idea — keeping a score card of all the birds you’ve seen! I got started right away.

There were some easy ones, S.F. Bay neighborhood birds like House Finch, Mourning Dove, Scrub Jay, Plain Titmouse, Red-tailed Hawk, Great Blue Heron, California Towhee – check, check, check, check, checkity, check. But for some species, I realized that I wasn’t sure if I had seen them. But hey, I was nine years old; I had seen a lot of birds. I just hadn’t kept track. So, I made a kind of on-the-spot, logical deduction: if the species name was preceded with the word “common,” then I no doubt had seen it in my near-decade on the planet, and I could safely check that species off. Good call, Allen. Off I went.

Common Eider? Check. Common Merganser? Check. Common Loon? Check. This was so easy. I cruised through the index. Common Tern? No doubt. Common Bushtit? Yep. Common Egret? Hundreds. Common Raven, Common Gallinule (what even was a gallinule?), Common Murre, and — how could I even imagine? — Common Teal. I wasn’t even on the correct continent.

But I lived in this blissful state of hyper-confident bird-listing for at least a few years. I am not sure what happened next, but I imagine I had some kind of epiphany. I would have been around twelve or thirteen. Perhaps I glanced at my dad’s San Francisco Chronicle, and saw a headline. “Liar Lying-pants Boy-birdwatcher Sentenced to 40 Years Hard Labor After Misrepresenting Life-List.” Perhaps it was after learning that the President himself had lied, and now he was resigning. For sure, I would be punished for this. Anyway, something clicked, and shame set in, big-time.

I realized I had only one course of action. I found my Robbins and I ripped out each of the index pages, one by one. Pages 327 to 340 — gone. All those boxes colored in, checked off — gone. Fortunately I got to my book before any member of the public saw it. It would have been my word against theirs. But now my scam was over, my secret was safe.

I never did keep a life-list after that. Like an addicted smoker, I couldn’t risk lighting a match without feeling the urge to inhale. Robbins and I didn’t spend much time together after college. National Geographic published the first of its North American guides in 1983, which added many species and corrected many worn-out names from the Golden Guide, while retaining its strengths. David Sibley eclipsed everyone in 2000 with a heftier but more comprehensive North American bird guide. Indeed, there were strengths to each of the new guides, and I acquired them all, but it was Robbins who was there for the launch of my bird-watching career. Robbins was the book I paged through for hours, remembering Latin names, the arrangements of taxonomic families, and forging a fake life-list of bird names, species seen and unseen.

Sometime in the mid 1980’s, I found a copy of Rich Stallcup’s Birds for Real, a thin but powerful booklet that catalogued the mistakes he found in Robbins. Some were mistakes to be sure. Others were simply western corrections based on Rich’s years of West Coast birding. I readily wrote Rich’s corrections into my copy.

Then not long after, I took the single best birding class ever offered, Joe Morlan’s “Birds of California” at City College of San Francisco. Joe did a page-by-page walk-through of Robbins, giving suggestions, tweaks, compliments – all of which I wrote directly into my increasingly scrappy guide. Of course it was my destiny, some years later, to marry a librarian who reserved a place in hell for people who wrote in books, right next to spider-squishers and wildflower-pickers. I have done my best to keep Robbins (and my many other margin-inked bird guides) out of her way.

Thank you, Chandler Robbins.

Allen Fish is a biologist, naturalist, volunteer coordinator, teacher, reader, writer, father, son, husband, brother, and student of all things feathered. He directs the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory. This post is reprinted with permission from his blog, Inner Nature Outer Nature.