Who named this bird and why?

By Steve and Carol Lombardi

So there I was, standing in a marsh staring at a bird that my Sibley’s field guide identified as N. nycticorax or Black-crowned Night-Heron. As I leafed through my field guide I found myself wondering where the scientific and English names came from, who decided on the spelling, why the scattered capitals, and really—who jammed those hyphens into the common name?

Of course, we all learned in high school how Carl Linnaeus invented binomial nomenclature in the 1700s, giving a Latinized Genus species name to every organism. Since 1895, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) has been the primary body for assigning scientific names to animals. (As you would guess, there’s an organization that names plants, too: the ICN.[1]) Thus, the history of the name N. nycticorax is well documented, and there is little argument about the bird’s scientific name, spelling, or capitalization.

However, it gets a little trickier when we start talking about common names. People have complained for hundreds of years about the lack of uniformity in common names of all living things. Yet there are only a handful of organisms whose names have been standardized by some organizing body.[2] Birds are one of these few.

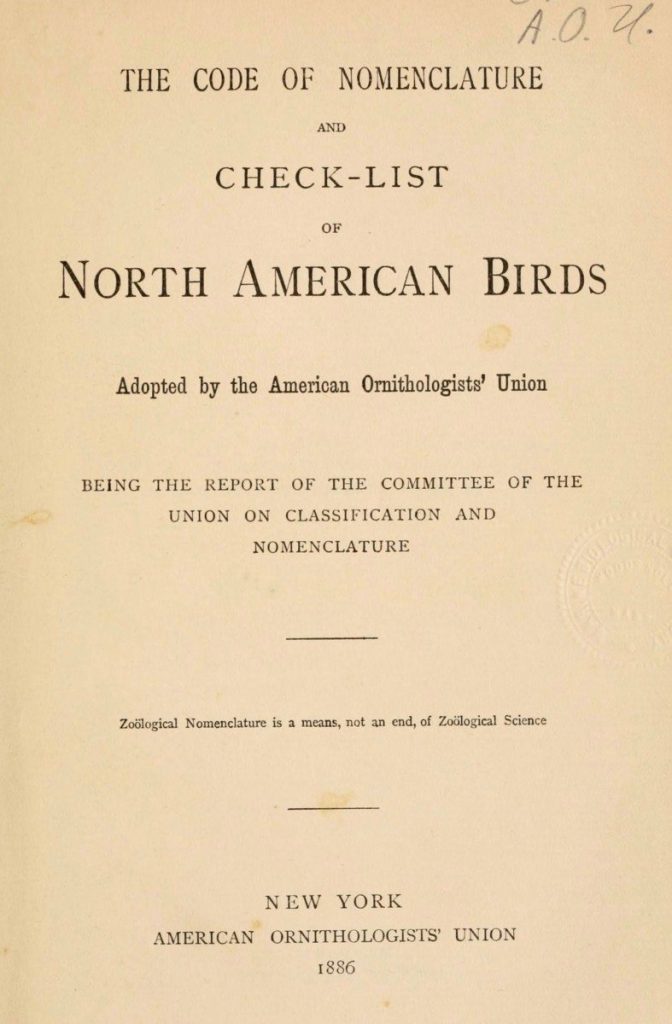

In the United States, the American Ornithological Society (formerly the American Ornithological Union and still usually referred to as the AOU) maintains—and occasionally rearranges—the taxonomy of bird species in North America. Reputable American field guides and online sources like the Cornell allaboutbirds website use the AOU taxonomy. The AOU Checklists link each scientific name with one standardized English-language common name.

The AOU uses a detailed protocol to determine the naming, spelling, capitalization, and hyphenation of both formal and common names. Hence, the bird staring at me with its unsettling red eyes is listed in the seventh edition of the AOU Checklist as Nycticorax nycticorax with the standardized common name “Black-crowned Night-Heron.” Note the hyphenated “Night-Heron.” The first AOU Checklist in 1886, wherein they made the case for standardizing common names and spellings, lists the bird as “Black-crowned Night Heron” (no hyphen).[3]

Capitalization, then hyphenation.

The practice of capitalizing common names goes back hundreds of years in the scientific community. The AOU capitalized common bird names even before their first edition of the Checklist, yet newspapers and most other general interest publications insist on using lowercase for common names. The National Audubon Society was schizophrenic in this regard: Their scientific papers used caps; the Audubon magazine used lowercase until 2014—when they finally switched to caps after a lot of inner turmoil and some spirited discussion.[4]

So that leaves us to wrestle with the hyphens. “Black-crowned” makes sense since the word “black” specifies the color of the crown, not the whole bird. But why “Night-Heron?” For over a hundred years, the name “Night Heron” was good enough—until 1983, when the sixth edition of the AOU Checklist switched to “Night-Heron.”

Whose idea was that?

It turns out that in 1978 Kenneth Parkes (the Parkes of the Humphrey-Parkes molt theory) wrote an article suggesting some changes to the spelling of common names[5]. One of his recommendations was to hyphenate the “group names” of birds to help identify a portion of a taxa as a separate group. For example, presumably “Night-Herons” and “Pygmy-Owls” differ enough from other herons and owls to be considered a separate group. Parkes (and the AOU, since they adopted Parkes’ system) believed that denoting these groups through the use of a hyphen would convey some additional (presumably phylogenetic) information that was missing from “Night Heron” and “Pygmy Owl.”

The deployment of these additional hyphens was descried by many scientists immediately and continuously. For example, when the International Ornithologists Union (usually referred to as IOC) began to standardize common names for all bird species in the 1990s, they were blunt in condemning the use of hyphens to distinguish group names.[6]

But so far, the AOU has not budged—leaving our field guides littered with extra hyphens and confounding our bird ID apps. So there I was, standing in a marsh staring at a bird and scratching my head over the puzzling punctuation of its name. The bird calmly stared back and seemed not to care about my confusion.

“What’s your name,” Coraline asked the cat. “Look, I’m Coraline. Okay?”

“Cats don’t have names,” it said.

“No?” said Coraline.

“No,” said the cat. “Now you people have names. That’s because you don’t know who you are. We know who we are, so we don’t need names.”

―Neil Gaiman, Coraline

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_nomenclature

[2] A bunch of Australians got together to standardize the common names of several thousand fish and other hydraulic organisms. Naturally, there’s an on-line database. http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/content/148

[3] Pages 68–69 of the first AOU “Check-List,” published in 1886: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/16484#page/7/mode/1up

[4] For a wonderfully entertaining account of this style change, read http://www.audubon.org/news/case-history

5] https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v095n02/p0324-p0326.pdf

[6] http://www.worldbirdnames.org/english-names/spelling-rules/hyphens/

Steve Lombardi is a long-time birder who gained most of his birding knowledge from taking GGBA bird classes. He has been GGBA’s volunteer Field Trip Coordinator for several years. Carol Lombardi is a birder and professional copy editor who keeps Steve’s sentences out of trouble.