Pterosaurs – older and bigger than birds

By Jack Dumbacher

Powered flight is perhaps the most iconic ability of birds. Their feathers and wings have set them apart from other vertebrates, and they have amazing adaptations that have allowed them to master flight, including special lungs and airsacs to capture oxygen incredibly efficiently, and hollow or reduced bones and no teeth to cut down weight.

There are many ways to get into the skies, and birds are not the only vertebrates that have evolved flight. Within the mammals, there are bats. The oldest known bat fossil dates to about 52 million years ago from the Green River formations in Colorado and Wyoming. Although bats are less efficient flyers than birds, bats are more maneuverable. Their wings consist of a thin membrane of skin called the patagium, stretched between their four finger bones and the side of their body. Because their fingers are so long and spread through the patagium, they have superb control of the shape and size of their wings, making them incredibly agile fliers.

But birds have been flying for nearly three times as long as bats. The oldest bird fossils are from Archaeopteryx, found in the Solnhofen limestone quarries of Bavaria, Germany, and these fossils were dated to about 150 million years ago. These fossil bones mark the beginning of birds in the fossil record.

Most of the close dinosaur relatives of Archaeopteryx were covered in feathers and some even had wings. We call this group of dinosaurs “Paraves,” and they include some four-winged dinosaurs (like Microraptor, having feathered forelimbs as well as hindlimbs) and many others that were fierce terrestrial carnivores, like the Velociraptor made famous by Jurassic Park. (The film incorrectly shows Velociraptor with scaly skin instead of feathers!)

Representatives of the most bizarre and largest flying vertebrates were also around at the time of Archaeopteryx. In fact, the first fossil of this group to be described was collected from the same Solnhofen limestone formation of Bavaria that produced the famed Archaeopteryx specimens. That fossil was described in 1784, and is now known as Pterodactylus antiquus, which derives from Latin for “ancient wing finger.”

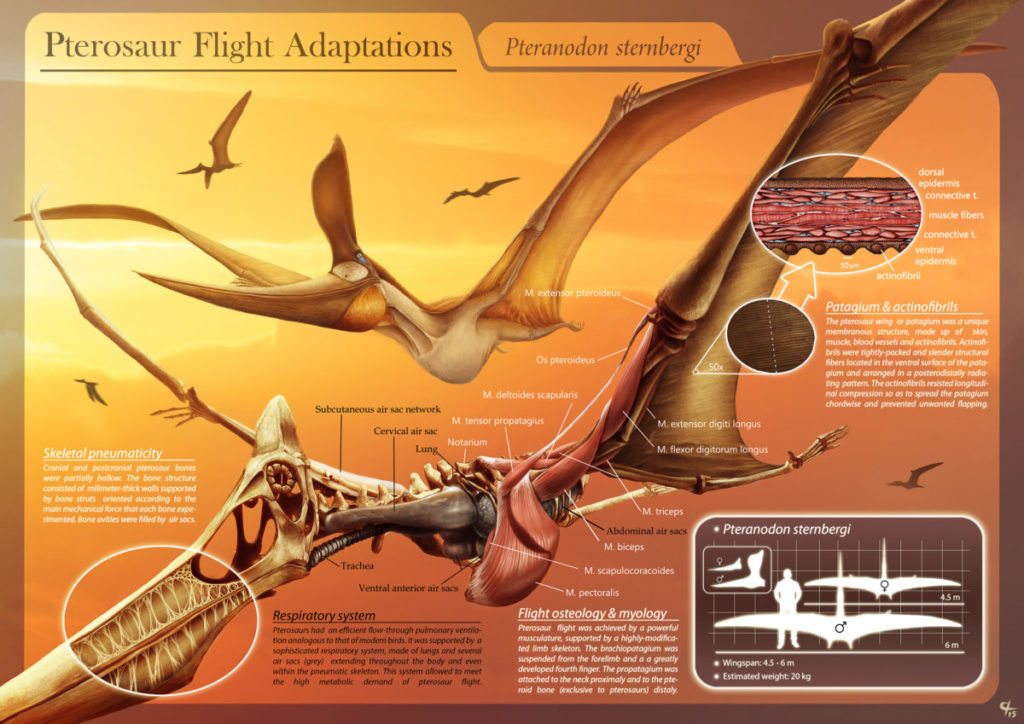

The pterodactyl is just one of a huge group of flying reptiles called the Pterosaurs. Pterosaurs were capable of powered flight, and species from this group of reptiles lived from 228 to 66 million years ago, dying out along with the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous. In many ways, their evolution is mirrored by that of birds. For example, pterosaurs started out with mouths full of teeth, but over time evolved a lighter, toothless, beak-like mouth. They also evolved a lung-airsac system similar to but predating that of birds by some 70 million years, that allowed efficient oxygen exchange for powered flight. Evidence from their lifestyle and body covering suggests that they were warm blooded as well.

They are also different from birds in many respects. First and foremost, the pterosaurs were not part of the tree of life called Dinosaurimorpha (which gave rise to the dinosaurs), and so the pterosaurs were NOT dinosaurs. They had no feathers, although at least some did have hair-like filaments that scientists call pycnofibers. And their flight is poorly understood.

As in bats, a membrane extends from the forewing and finger bones to provide shape and structure to the open wing, but the pterosaurs use only a single finger at the front of the wing to support the wing. The patagium, or wing membrane, of the pterosaurs was thicker, stronger, and more complex than that of bats. The pterosaur patagium included layers of muscle fibers as well as connective tissue called “actinofibers” that may have provided strength and support, and helped shape the wing like the battens on a sail. Many of the pterosaurs also evolved strange crests and head shapes, whose purpose is not understood.

Pterosaurs were the largest animals ever known to fly. Although many pterosaurs were small and in the range of modern bird sizes, several had wingspans that exceeded five meters (16 feet). In contrast, the largest flying bird was the extinct Argentavis magnificens, or the Giant Teratorn, which had a wingspan of 5-6 meters (17-20 feet) and stood about 1.5-2 meter (5-6 feet) tall. Although this is extremely large for a bird, the are dwarfed by the larger pterosaurs.

The largest of the pterosaurs was Quetzalcoatlus northropi, which had a wingspan of 10-11 meters (up to 36 feet!) and stood 4-5 meters tall (16 ft). With such large bodies and wings, they are believed to have flown at fast speeds (up to 75 miles per hour) and could cover large distances. Based upon fossil footprints from pterosaurs, they were believed to walk on four legs, with the wings folded back along the arm, and the other fingers opened out to form a hand or paw. This would have been useful for supporting their large bodies while on the ground.

Right now, the California Academy of Sciences has a traveling exhibit featuring pterosaurs, so you can see some real pterosaur fossils, life-sized models of pterosaurs, and learn about their biology. The exhibit was produced by the American Museum of Natural History and will remain on site through January 7, 2018.

Combine a visit to Cal Academy to see the pterosaur exhibit with a nearby Golden Gate Bird Alliance activity! We hold monthly habitat restoration sessions in Golden Gate Park – at the Bison Paddock on the third Saturday of each month, including October 21, and at North Lake on the fourth Saturday of each month, including October 28. We also host a bird walk in the San Francisco Botanical Garden in Golden Gate Park on the first Sunday of each month. See goldengatebirdalliance.org/volunteer for details on the habitat restoration events and goldengatebirdalliance.org/fieldtrips for details on the bird walk.

Jack Dumbacher — curator of ornithology and mammalogy at the California Academy of Sciences — serves on the Golden Gate Bird Alliance board and chairs our San Francisco Conservation Committee.