Bird Tongues

By Nancy Johnston

Birders quickly learn to use bird bills to help identify species. Bird tongues, if we could easily see them, would also be helpful in identifying species. This blog is to whet your tongue about bird tongues and highlight the diversity that evolution has brought to avian tongues.

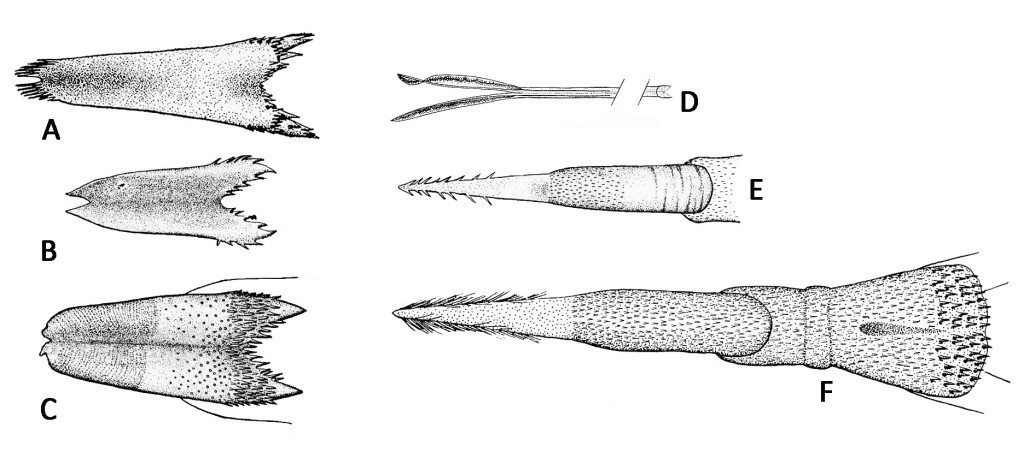

First, most birds have pretty prosaic tongues. They look somewhat similar to ours but can have some interesting extra features. As shown in Figure 1, the tips can be fringed or split and the root of the tongue may have backward-facing barbs. It is not clear if the fraying or splitting helps in acquiring and eating food, but the backward-facing barbs are useful for moving food to the gullet. This is needed because birds don’t swallow the way we do. These tongues vary quite a bit in width, thickness, amount of fraying, barbs and their placement, etc. (Note: Drawings are not to scale.)

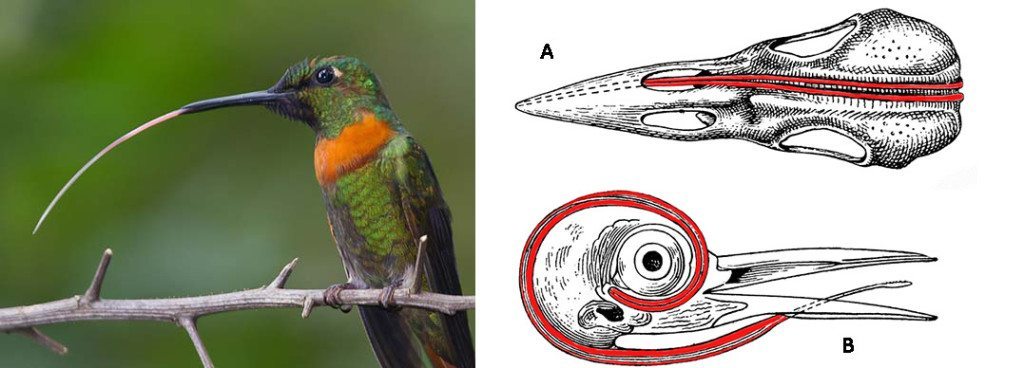

Species such as woodpeckers and hummingbirds have more interesting tongues. Most of these birds have tongues that can extend far outside their bill (Figure 2). For these birds, the boney/cartilaginous apparatus that supports the tongue wraps around the skull under the skin, usually terminating in the right nostril (Figure 3). Extending their tongues lets hummingbirds reach into flowers for nectar or lets woodpeckers get insects from crevices in trees.

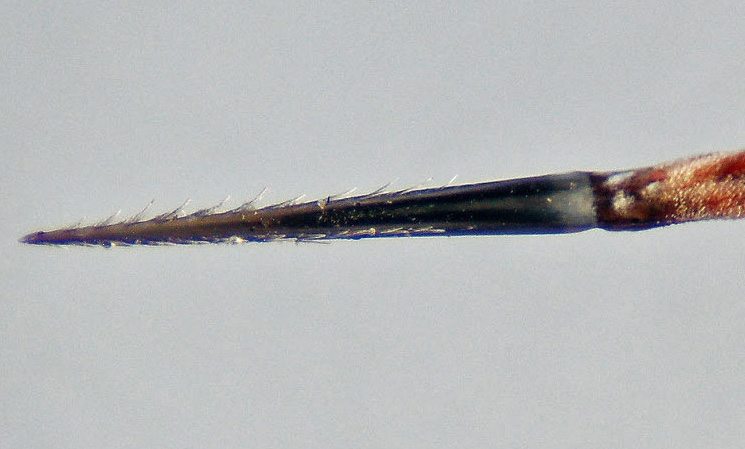

In the case of woodpeckers (Figure 4), the tip of their tongue can also be barbed or covered in sticky fluid that helps them capture insects. Sapsuckers have shorter tongues with hair-like structures for gathering sap from trees.

Figure 3: Pictures of the tongue and the supporting apparatus (red). A: shows how the horns go around the skull and terminate in the right nostril, e.g., Northern Flicker. B: shows how the horns can go around the eye, e.g., picus. Modification of a picture from etc.usf.edu/clipart/

Birds that filter out food particles from mud and water have the most complicated-looking tongues. Their tongues have papillae (barb-like or hair-like structures) of various sizes and shapes that help strain out food particles. Two good examples of this behavior are the flamingos and various ducks. We know how flamingos, with their head upside down, sweep their bills back and forth through mud and water, straining out food particles. Ducks such as the Cinnamon Teal (Figure 5), Mallard, and the Northern Shoveler will sometimes filter feed and use their tongue like a pump. When they depress their tongue, it allows water and mud to fill the mouth. Then they press their tongue against the palate and the water/mud is ejected sideways between the papillae, capturing the solid food particles. Geese do some filter feeding too, but they also use their muscular tongue and bill to clip vegetation close to the ground by gripping and tearing off plant stems.

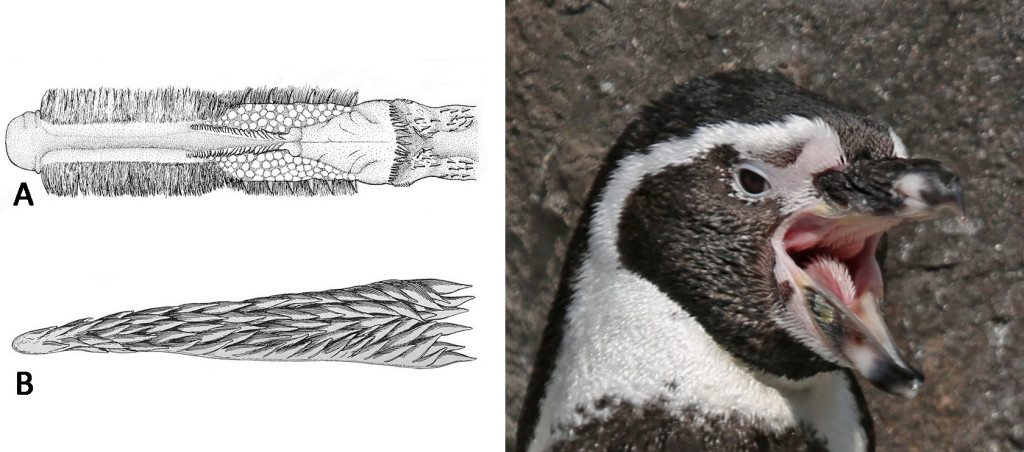

Some birds have tongues with spines covering much of the tongue and sometimes the roof of their mouths. Their bill also has spiny ridges. These spines and ridges allow these birds to catch and hold on to fish. Prime examples are penguins (Figure 6) and the Red-breasted Merganser. Not all fish eaters have tongues with spines, though. Some just use their strong bills to catch and hold on to their prey.

Lories and some parrots have a tongue tip that is very bushy. This type of tongue is very good at brushing up pollen and nectar from flowers. When the tongue is not extended, the papillae lie flat.

The previous examples demonstrate how the tongue helps a bird acquire and eat various foods. Some birds, though, have small or rudimentary tongues that are not thought to play much of a role in catching or manipulating food. Small tongues may permit a bird to swallow large food items such as fish. Examples of birds with rudimentary tongues are pelicans, cormorants (Figure 7), emus, and ostriches.

Other interesting things about birds’ tongues include how some nestlings such as mannikins, parrotfinches, and silverbills have tongues with black spots and/or a band. Like the nestlings’ gape, these markings may aid the parents in directing food to their mouth.

While the tongue is critical to our speech, it is believed that birds’ tongues do not play a major role in modifying sounds, except possibly for parrots. Some recent research has shown that parrots’ tongue placement can cause significant frequency changes.

In the 1800s, when taste buds were initially discovered, they were not thought to exist in birds. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that birds’ taste buds were discovered. Humans have over 10,000 taste buds that are primarily found on our tongue. Birds have significantly fewer.

For example, chickens have around 24 taste buds, pigeons 27 to 59, and parrots 300 to 400. The placement of birds’ taste buds is also different than ours. In birds, they are primarily found at the base of the tongue and on the roof or floor of the mouth. It is believed that they are not found on the anterior (front) part of the tongue because it is frequently hard and horny. It is believed that birds can taste sweet, salt, brine, bitter, lipids (fats), and sugar concentrations. Dunlins and Sanderlings use their taste buds to recognize where worms have been crawling in the sand.

While there is quite a bit of research available on the tongues of birds, there are still many species where little is known about the role that the tongue, or even the beak, plays in the acquisition and consummation of food. Part of the problem is the difficulty is studying the tongue in live birds. New methods such as high-speed photography are helping to solve some of these questions, but many challenges remain.

For example, Rico-Guevera and Rubega published a paper in 2011 that used high-speed photography to understand how hummingbirds acquire nectar. The two researchers disproved a theory first proposed in 1833 that suggested hummingbirds used capillary action; instead, it turns out they trap nectar using the split tip of their tongue and the fringe-like lamellae.

Even with this discovery, though, the researchers acknowledged that they don’t yet understand how hummingbirds swallow the nectar once they have trapped it.

———————————–

Nancy Johnston is a retired computer scientist who got interested in birding and photography eight years ago when she saw her first Burrowing Owl at Cesar Chavez Park in Berkeley. Nancy researched bird tongues as a participant in the 2014 Master Birder class co-sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance and the California Academy of Sciences. You can read the full paper she wrote on the topic (including more illustrations!) at Avian Tongues. Our next Master Birder class will start in February 2015. For information on the class and how to register, see the Classes page of our web site.