Birding by Ear with help from AI

By Margot Bezrutczyk

I’ll probably never know what it was: the bird that sang such complex, liquid song in the thicket of bay laurel that morning on Bolinas Ridge. I tried and failed to come up with a mnemonic, resorting to simile: “It sounds like an Ewok and a robot fighting. It sounds like a computer drowning.” I climbed up some fallen branches hanging off the trail in an attempt to see the bird, but several crows and a wren joined the chorus and began scolding me. I was brand-new to bird identification, armed only with my field guide and binoculars, birding alone during the pandemic, and eventually I simply had to walk away. I found birding in the woods both exhilarating and frustrating, because it was so difficult for a beginner to even know what to listen for.

Then I discovered BirdNET.

BirdNET is a sound ID app developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in partnership with Chemnitz University of Technology in Germany. I’ve been a bit of an evangelist for BirdNET since I started using it, and I was happy to see that similar artificial-intelligence (AI) technology has recently been integrated into the Merlin app as a “Sound ID” feature.

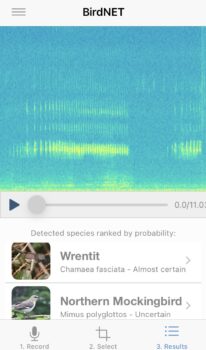

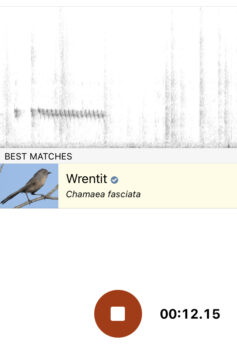

Both apps are free, and both work by recording spectrograms of the sounds detected by your phone. The spectrogram—a visual representation of audio frequency and signal strength or “loudness”—is processed through a neural network that returns one or more predictions based on both the spectrogram and your location. A sound may represent multiple bird species, which the app can identify simultaneously.

You have the option to share your recordings with Cornell’s Macaulay Library, where they’ll be used to improve the quality of IDs in the future. I usually don’t do this because because many of my recordings end with something like, “…it’s just a f*∆king squirrel, again.”

Shortly after downloading BirdNET, I held up my phone towards the cacophony of an oak woodland one April morning, and finally begin to distinguish signal from noise. The first test: I was able to determine that a certain call I’d been hearing for weeks was the song of a Wrentit, an untrustworthy-looking little grey bird I’d seen in my Sibley book and longed to lay eyes on: It was right here all along!

With an idea of what to look for, it wasn’t long before I was able to spot the Wrentit and learn its song by heart. Being able to view the spectrogram in real time makes memorizing vocalizations that much easier.

I have found Merlin’s Sound ID to be remarkably accurate as long as the signal is clear. Predictably enough, the algorithm doesn’t do well in areas with a lot of human activity, and if the sound is faint or background noise high, some spurious results may be returned.

Which brings us to the controversy: Will birders suddenly start adding all kinds of wild sightings on eBird based on predictions from the app? Some have suggested that eBirders should write “sound ID by Merlin” or “ID assisted by Merlin” in a note if they opt to add it to the eBird database. Personally, if I am unsure about the call and rely on Merlin or BirdNET, I don’t include that sighting on an eBird list. I’d use that information to try to actually spot the bird and attune my ear more closely in the future.

There are a few meaningful differences between the two Cornell Lab of Ornithology sound ID apps. BirdNET has a few advantages: Currently it features 984 species of North American and European birds, while Merlin supports about 450 and works in North America only, though this may change in the future.

With BirdNET, you can select the region of the spectrogram that best represents the sound you’re trying to identify, and importantly, it returns a quality score for its prediction that will help birders decide how much to trust the ID. On the other hand, Merlin’s Sound ID makes it easy to submit audio files you have previously recorded on your phone with any other sound recording app, and unlike BirdNET, works offline—though offline ID seems to be significantly slower.

Holger Klinck, one of the researchers working on BirdNET, says, “Fundamentally, both apps are using similar deep neural network approaches. One difference is that the Merlin’s [Sound ID] algorithm is exclusively trained with data hosted by the Macaulay Library. BirdNET uses additional (non-Cornell) data sources.”

Klinck adds, “We are working on a paper that looks at the spatial distribution of a variety of songbird dialects. This research couldn’t be done without all of your [birders’] great contributions.”

Though I have not personally performed a side-by-side comparison with other bird vocalization ID apps, others have, with the results resoundingly in favor of BirdNET. (However, Merlin’s Sound ID feature was not available at the time and not included in those comparisons.)

I expect experienced birders may find the Merlin and BirdNET sound ID apps amusing, or use them for an occasional second opinion about a distantly-heard call. But for those of us who are new to learning birdsong, they are an indispensable tool. I may never know who was singing on Bolinas Ridge that morning, but next time I’m bewildered by a song, I’ll be ready.

Margot Bezrutczyk is a plant biologist at Lawrence Berkeley National lab, where she studies root-microbe interactions. She is also interested in biodiversity of California native plants and birds, and loves sharing her passion for the natural world with others.