Birding Hotspot: Lake Merritt

This is the second in an occasional series of reviews of Bay Area birding locations. Do you have a favorite site you’d like to share? Email idebare@goldengatebirdalliance.org.

By Marissa Ortega-Welch

The average jogger running around Lake Merritt or average family picnicking on its shores doesn’t realize that Lake Merritt isn’t actually a lake. Most Bay Area birders, however, know that this gem of a birding spot smack dab in the middle of Oakland is actually a tidal lagoon, connected to the greater San Francisco Bay.

Local birders who want to view wintering waterfowl without driving all the way to the South Bay or the Sacramento Valley are rewarded with our annual vagrant Tufted Duck, Ring-necked Ducks, the occasional Redhead, and the rare Barrows Goldeneyes if we can pick them out from the Scaups, Canvasbacks, and over ten other species of waterfowl that raft on the lake’s waters.

Lake Merritt is an arm of the greater Bay estuary and the mouth of many creeks draining the surrounding Oakland hills, most notably Glen Echo and Indian Gulch Creek. Before Oakland grew up around it, the lagoon was a wetlands ecosystem like much of the Bay, with large fauna such as deer and elk grazing nearby, abundant fish, and thousands of waterfowl calling the place home for the winter.

After Spanish colonization and the Gold Rush, Oakland developed as a city and so did the shoreline of what was then called “Laguna Peralta.” The homes along the lagoon dumped their sewage directly into its waters, which seemed convenient until the tide went out and residents were left with the nasty sights and smells of their own domestic discharge. The mayor of Oakland, Samuel Merritt, was one of these homeowners and had a grand plan to remedy this unsightly problem. He petitioned the City Council for help, and used both tax dollars and his own money to build a dam on the outlet of the lagoon, along today’s 12th Street, limiting the tidal changes so that the sewage would remain submerged and out of sight.

But another problem remained for homeowners like Merritt – hunters who were attracted to the lagoon’s waterfowl. The story goes that Merritt got tired of poachers on his land and bullets zinging through his property. The last straw was when a stray bullet hit his neighbor’s cow and another went through his own home window, all in one week. To get rid of the hunters once and for all, he appealed all the way to the state level, petitioning that the lake be turned into a protected refuge where no waterfowl or any animal could be hunted. The year was 1870. No such protection had been created yet in this country for wildlife. Yellowstone, the country’s first national park, would not be established until two years later.

What many birders may not realize is how enthusaistically the city took to providing for the birds on its municipal refuge. In 1915 a Bay oil spill entered the lake, soaking the ducks. Volunteers cleaned up the waterfowl and the City Council voted to pay for feed for the recuperating birds. This sparked the beginning of a feeding program that continued for decades and became a spectator event for lake visitors. The ducks were called to the shoreline with a bell every day at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Paul Covel, the City Naturalist from the 1950s to the ‘70s said at the time that “The daily afternoon feeding at the fresh-water pool has become the city’s biggest free attraction.”

Another bird-related spectator sport was added to the lake in the 1920s. With supervision from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a duck-hunting businessman from Piedmont launched a bird-banding project. “Sprigs and Baldpates” — 1920s-speak for Pintails and American Wigeons — were lured with grain feed into a caged area on the bird sanctuary beach near the Rotary Nature Center. Then the cage doors were flung shut and volunteer banders spent the rest of the day banding the trapped birds, on average about two thousand birds a day! Pigeons and domestic ducks species that were inadvertently caught were given away to volunteers, institutional mess halls, or passersby. As Covel explained in his 1978 book People are for the Birds, those were different times, and everyone and their mother knew how to butcher and prepare such a bird for dinner.

The ‘60s saw a decline in Pintail and Wigeon populations, due to the increasing development of their estuary feeding grounds in the San Francisco Bay. The banders needed to switch to a different species. Scaups and Canvasbacks were still plentiful on the lake but they were shyer and couldn’t be lured to land like the other birds. Instead the banders got creative and devised deep water traps for the middle of the lake. It wasn’t easy work, as they were often knee deep in the not-so-pristine waters. But they were successful. The banding station on Lake Merritt was, according to Covel, “one of the principal early diving duck banding operations on the Pacific Flyway.”

Another industrious Oakland mayor, John L. Davie, made a series of improvements to the lake in the 1920s that his opponents referred to as “Davie’s Follies.” This included declaring the northeast arm of the lake a waterfowl refuge, blocked off with log booms in the winter to keep boaters away from rafting birds.

Mayor Davie also had the lake dredged, and used the material to build the first of five bird islands that provide a safe haven from dogs and humans. The rest of the islands were completed in the ‘50s. In the summer, these islands are now home to nesting Double-crested Cormorants, which GGBA’ volunteer docents introduce to lake visitors every year through scopes.

Today, winter visitors to Lake Merritt are rewarded with over one hundred and forty species of birds — both the diving and dabbling ducks, grebes, coots, cormorants and pelicans on the water as well as the passerines, woodpeckers and hawks hiding in the oaks on the lakeshore.

The most common route for birding the lake is to begin at the Rotary Nature Center in front of the bird islands and then walk east along the lake shore toward what is referred to as the Embarcadero, with the series of pillars and fountain. The duck diversity is highest nearest the bird islands; further east there are large rafts of Scaups intermingled with Ruddy Ducks and Grebes. The Tufted Duck often likes to hang out nonchalantly near the fountain at the Embarcadero.

To make a loop of the route, you can circle back through the trees and look for songbirds in the Cork Oaks. If you want a longer walk, you can keep heading along the lake shore to the estuary outlet near 12th Street. If haven’t found the Barrows Goldeneye yet, you might find them there. (You can walk all the way around Lake Merritt, following detour signs on the western end where there is currently construction.)

To examine the history of bird populations on the lake over time is in some ways to see a sad story of decline in bird diversity overall throughout the Bay Area. On the other hand, we’re still lucky to have such a wide array of species right in the middle of an urban area.

It’s an especially exciting time for the lake right now, because the Measure DD bonds passed in 2002 have funded a massive restoration project, including a re-opening of the channel that connects the lake to the rest of the bay. While Merritt’s dam never completely blocked the bay waters, it did block larger marine organisms such as leopard sharks and other big fish from entering the lake. It also limited the tidal influence on the lake. An increase in this tidal influence and in the marine organisms bodes well for the birds of Lake Merritt. And that in turn bodes well for birders like us visiting our local wildlife refuge.

————————

About Lake Merritt

Location: Downtown Oakland, CA.

Habitat: Estuary, Oak Woodlands, Urban

Key Birds: Resident – Black-crowned Night Heron, Oak Titmouse, Nuttall’s Woodpecker. Summer – Forster’s Tern, Allen’s Hummingbird, White Pelican. Winter – Horned Grebe, Canvasback, Redhead, Ring-Necked Duck, Tufted Duck, Greater and Lesser Scaups, Bufflehead, Common and Barrow’s Goldeneyes.

Ease of Access: Paved walking trail from Rotary Nature Center heading east and then south around the lake all the way to dead end at 12th Street. Trail is wheelchair accessible.

Getting There: Parking is available on Bellevue Avenue. With an entrance on Grand Avenue, it takes you into Lakeside Park and alongside the Rotary Nature Center. Fee is is $2.00 for two hours (or $10 for all day parking) during weekdays and $5 all day parking on the weekend and holidays. For public transit, the Rotary Nature Center and adjacent birding area is an easy 15- or 20-minute walk from the 19th Street Oakland BART station. AC Transit also runs bus lines near the lake.

Nearby services:

Restrooms are behind the Rotary Nature Center, behind the Boat House, and next to the Lakeshore Library across the street from the Embarcadero columns. There are many picnic tables and benches along the lake shore, and a drinking fountain near the Rotary Nature Center. There’s a children’s playground just east of the Nature Center.

Nearby cafes/ restaurants:

Lakeshore and Grand Avenue near the northeast side of the lake offer a long string of eateriess, from trendy upscale restaurants to inexpensive burger and Asian places . Here are some highlights:

- Coffee with a Beat – 458 Perkins Street. Locally owned coffee shop, closest coffee shop to the Rotary Nature Center

- Room 389 – 389 Grand Avenue, between Ellita and Staten Ave. Locally owned, serves locally roasted coffee and pastries.

- Grandlake Farmers Market – Grand Ave. and Lake Park Ave. Saturdays 9am – 2pm. Coffee, prepared hot foods, local produce and crafts.

Guided Walks:

Golden Gate Bird Alliance offers a free monthly bird walk at Lake Merritt, led by Hilary Powers and Ruth Tobey. Visit the Field Trips section of the GGBA website for details.

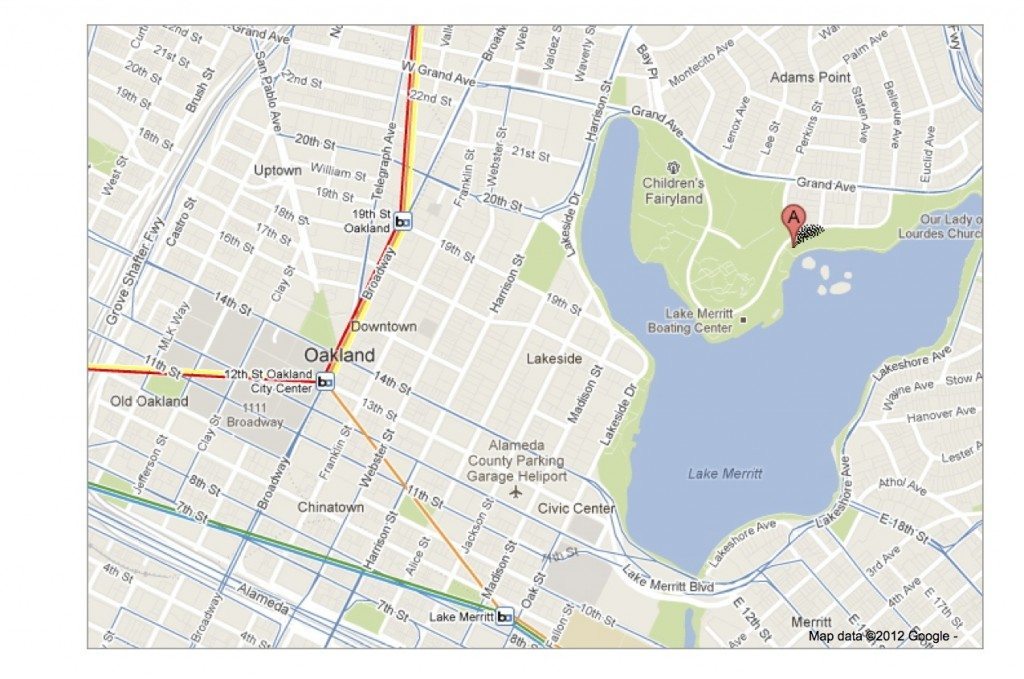

For More Information: The City of Oakland provides information on Lakeside Park, which borders the northern side of Lake Merritt. The map below shows the Rotary Nature Center (A) and the nearby bird islands.