eBird Streaking Leads to Better Birding

By Marjorie Powell

I followed the lockdown rules carefully; I went out once a week for groceries; I went birding, alone, once or twice a week. I read book after book—history, biography, fiction, emptying the shelves of books collected over the years. Then Golden Gate Bird Alliance member and birding instructor Dawn Lemoine asked me to meet her, masked, at the Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary platform in Alameda. This evolved into birding twice a week with Dawn and two other friends. Occasionally we included other birders, especially when we traveled a distance seeking special birds, such as to Staten Island for the Sandhill Cranes.

Dawn encouraged me to keep an eBird list and tutored me on the mobile app. She taught me to use the four-digit “Quick Codes,” a slight variation from breeding codes, to bring up the bird’s name quickly on the eBird list. Because eBird uses them, I learned birds’ official names: A white pelican is an American White Pelican or AWPE; a raven is a Common Raven or CORA. Perhaps the most esoteric eBird skill is speaking Quick Codes: For example, “SNEG or GREG?” is a request to determine if the white bird you spotted is a Snowy or a Great Egret.

Knowing that eBird data might be used by researchers, I felt pressure when birding alone to list all the birds correctly. I began to study each bird a little more carefully than I had when my “list” was notes on a scrap of paper stuck in a bird book. More and more birds became instantly identifiable by size, shape, face pattern, location, and even sound. That large white bird must be a Great Egret… the v-shaped tail of a flying black bird makes it a Common Raven… a wren with a white eyebrow is a Bewick’s Wren.

More eBird skills followed—selecting an existing eBird hotspot rather than creating my own, estimating numbers of birds, learning about the half circle (which means “uncommon at this location and time of year”) and full circle (meaning “rare and must be described before eBird will let you submit the list”) after a bird’s name on the eBird list. I learned about justifying a “rare” bird or an unusually large number of birds, and signing up for a county alert, a “needs list” (birds seen in the past 24 hours that you’ve not listed this year) or rare bird list. And I survived my first two questions about an entry from the “eBird police.” (In my experience, they are always polite and diplomatic).

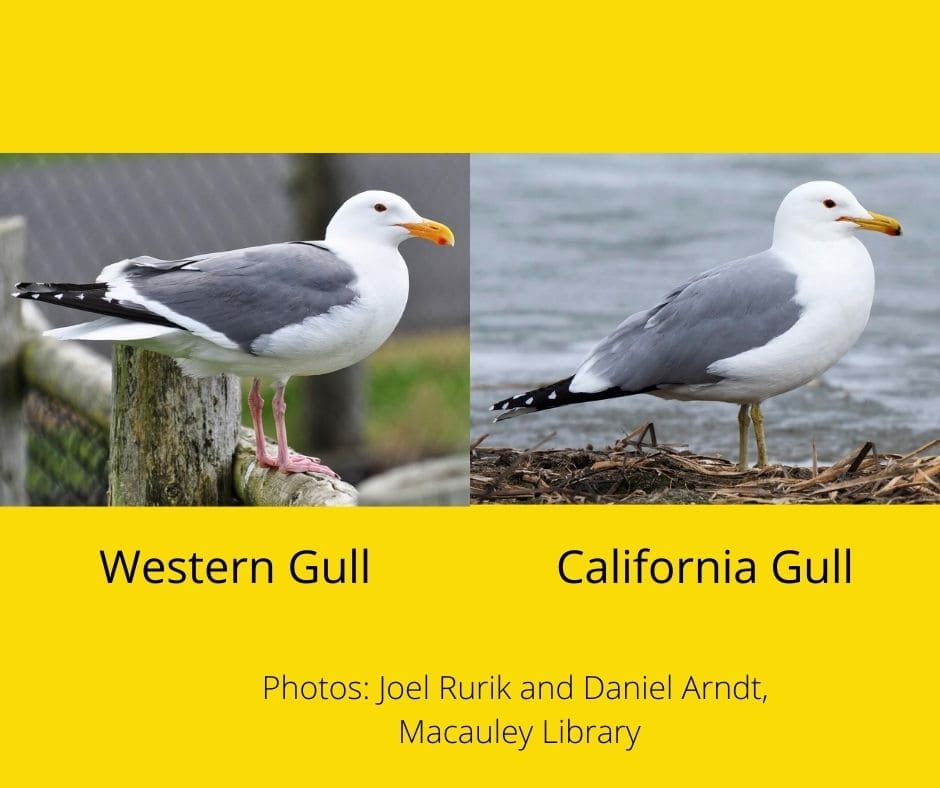

My developing eBird skills were matched by new search techniques: I learned to check towers for raptors and snags for woodpeckers, and look in a group of circling Turkey Vultures for a hiding hawk. As our birding foursome struggled to identify an unknown bird, I practiced more identification techniques. Is the bill long or short, fat or thin? Does the bird have a supercilium (eyebrow)? Is the gull’s tail white, indicating an adult, so leg color might provide a clue to its species? Is the bird in basic or alternate plumage, or in the middle of a molt? Is it a juvenile?

Smartphone apps downloaded at Dawn’s suggestion helped with some identifications. As we worked through identification after identification, I learned to look more carefully at various parts of the bird—bill shape, size, and color; eye color of gulls; wing length and color pattern; head size and face pattern. Identifications became simpler, and my county list expanded.

Other members of my foursome pointed out distinct bird calls and I braved Denise Wight’s birding-by-ear class. I remember my excitement when I first recognized the call of a California Quail and found it, and then a second and third quail. I learned that West Coast Red-Wing Blackbirds have a slightly different accent from those I knew on the Chesapeake Bay. The pitch of Elegant Terns’ incessant calls now lets me identify them before I see them foraging at Elsie Roemer.

Our group developed eBird goals: maintain a birding “streak” (number of consecutive days submitting or being named on someone else’s eBird list), seeing 100 birds in each of the nine Bay Area counties or, less ambitiously, my goal to see the most species in a particular hotspot than any other eBirder in 2020. Because I was going there often for another reason, I chose Seaplane Lagoon on Alameda’s old naval airbase. First I discovered that I’d submitted the most checklists for that site during 2020. Then I realized that I’d listed the most species there for 2020, as well as for all eBird time. (I do know at least one person who has seen more birds there but doesn’t use eBird).

Birding daily, nearby locations eventually became too familiar. So occasionally I ventured to new locations, perhaps because someone had reported a bird on my “year needs list.” That led me to some of the locations where people see species that are uncommon in Alameda County: the winery visited by Mountain Bluebirds in winter, or Mines Road for the Phainopepla that some birders have seen. (Not me, yet). First with birding friends and eventually on my own, I went looking for birds reported on the Alameda County rare bird list.

Patient, careful, and methodical looking can be helpful. My first lesson in studying a flock was Dawn’s assignment to find a Eurasian Wigeon in a mass of American Wigeons. I honed my observation skills each time we searched for rare birds, studying each Western and Least Sandpiper feeding along yards of mud at the water’s edge to find the Red-Necked Stint, and studying the peeps on the sandbars of Frank’s Dump looking for the Semipalmated Sandpiper.

In September, approaching 100 days of consecutive birding, I realized that I had unintentionally started my own “streak.”

It was then that I admitted that I wanted a good, lightweight spotting scope. I carried others’ scopes on several walks, thought about the money I’d saved from Covid-canceled trips, reviewed Dawn’s research on magnification, weight, and prices, and called Out of This World Optics, the wonderful Mendocino optics store. Once I made my purchase, I had to master my new equipment—attaching the scope to the tripod, keeping knobs at the right tension, putting the lens cap in a secure location. Next came learning to find the bird, zoom, and focus. And still more identification skills: What color is the gull’s eye? Can I see the color of the diving tern’s bill? Does the light orange color on the dowitcher’s breast go all the way to its tail? Do the bird’s primary feathers extend beyond the tail?

Many of these identification skills, I realize, were taught by GGBA instructors in pre-pandemic classes. While GGBA Zoom classes have been helpful, I’ve missed the field trips. It’s easier to apply what I’m learning when the instructor is pointing to a bird and talking about specific features than when I’m looking by myself.

But my streak keeps growing. Some days, I’m anxious to go birding; other days I ponder where to go. Occasionally birding is squeezed among appointments. Then, in 2021, I braved a birding trip to Hawaii and had to fit birding into the travel days—15 minutes just after dawn at Elsie Roemer before my ride to the airport, then birding outside the Big Island airport coming home.

While Dawn’s eBird streak will always be longer than mine, my streak is now over 400 days. I’ve seen 226 birds in Alameda County so far in 2021. And while there are many birds that still elude me, I’m clearly a better birder, thanks to a scope, better binoculars, several GGBA classes, and 400-plus days of practice.

A casual birder for many years, Marjorie joined Golden Gate Bird Alliance when she retired and moved here from the Chesapeake Bay. She started to become a more serious birder, taking classes and going on field trips, including Birdathon trips. A member of Friends of the Alameda Wildlife Reserve (GGBA’s Alameda conservation committee), Marjorie coordinates a continuing series of articles about birds seen within city of Alameda that is published monthly in the Alameda Sun.