Field Guide: An Artist’s Approach to Avian Taxonomy

By Christopher Reiger

In March 2020, I was excited. After 15 years of full and part-time jobs in administration and communications, I was finally in my studio five days a week and our two young boys were both in daycare programs. Creatively, I was cranking. In addition to a number of in-progress illustration and design jobs, I’d just completed studies for eight new works on paper. On social media, I shared a photo of my studio wall covered with freshly-pressed sheets of watercolor paper; the caption read, “Those blank sheets? They won’t be blank for long.”

Overnight, though, the pandemic made me a stay-at-home dad. Because the boys were so young (4 and 2 at the pandemic’s start), it was challenging, but, like parents everywhere, I made do. Yard exploration and reading were our go-to sanity-saving activities. Outside, we flipped fieldstones in search of ring-necked snakes and arboreal or California slender salamanders, and we watched California scrub-jays, bushtits, oak titmice, acorn woodpeckers, and many other local bird species work through the valley and coast live oaks. Inside, we embraced twice-daily epic story blocks, reading The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings, the Narnia Chronicles, the Harry Potter series, Wind In The Willows, The Jungle Books, and more. By the time the boys were asleep at day’s end, I was beat; my only working window was 8 p.m. to midnight, but “dadding” exhaustion made it difficult for me to take on many illustration/design gigs, and my art practice was completely fallow.

Still, bleary though it was, my mind needed a creative outlet. In the days’ interstitial spaces, I started turning over an unrealized idea I’d jotted down in a sketchbook years ago – “create bird species paint chips.” There was a germ of something exciting there, but what?

Then came the summer of 2020. As our society wrestled with racial injustice, past and present, I found myself thinking a lot about how we humans classify and catalog life. The social implications of our evolved human impulse to categorize are generally grim (see: human history), but that same proclivity allows us to better appreciate evolution and the relationship between species, subspecies, and ecotypes. As a natural history nerd, I value taxonomy’s utility, but I’m also enamored of its flux and ever-provisional nature. I decided that the “paint chip” idea must be realized as a project that playfully celebrates and critiques the necessarily imperfect science of taxonomy. To work, it would need to be equal parts design, data visualization, conceptual art, and bird lover’s flight of fancy.

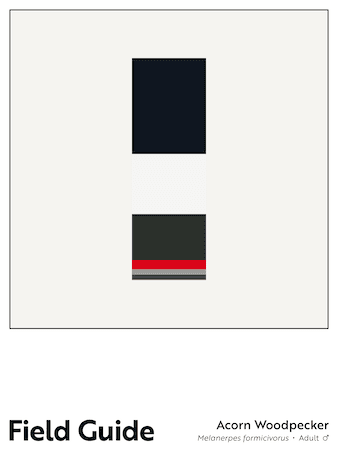

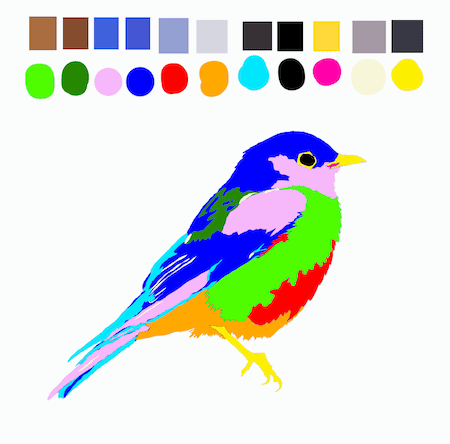

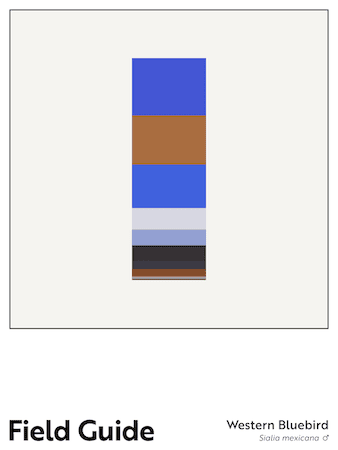

Over 16 months at home with the boys (until they started in-person First Grade and preschool), I devoted a little time each week to advancing the project. After conceptualizing and sketching, I began digital experimentation. I decided to consider each bird species in profile, with its legs and feet visible (even for divers like loons, which we usually see on the water or in flight). The bird’s colors (plumage, legs, beaks/bills, and eyes) would then be isolated and the percentage of each calculated. The colors in each column would be stacked according to those percentages, with the largest share at the column’s top and the smallest share at the column’s base. There were some technical hiccups and frustrations as I worked out the kinks, but by early 2021, I’d landed on a process I was pleased with.

I begin each poster by sourcing between 15 and 30 high-resolution photos of the featured bird. The photos are taken in different lighting situations (e.g., a sunny day versus a cloudy day). Next, I isolate each of the bird’s colors, carefully comparing them in the different light. For example, the “whites” on a California scrub jay (Aphelocoma californica) will appear considerably “warmer” in sunlight and much “cooler” in shade, so I have to study the many photos to find the most accurate “neutral” color and value. After each of the bird’s “true” colors is determined, I create the bird’s “palette,” and then a “map” of the species viewed in profile, carefully assigning color territories. I don’t use the bird’s actual colors for this map; instead, I key the bird’s palette to bold neons and saturated primary colors which stand in marked contrast to one another. The high-contrast nature of the map makes it easier to define the color percentages using histogram tools, which provide numerical data on color distribution. Those data then allow me to calculate the exact percentage of each color. I then review the spreadsheet data and determine the height of each color band on the bird’s color column. Finally, I create the column and finalize the poster file. The bird’s English common name and its scientific binomial are noted on the poster’s base, along with information on the bird’s sex, and, if relevant, plumage variation.

One of the project’s principal pleasures, for me, is the regular surprises. I’m learning new things about bird species I felt I knew very well. Take the turkey vulture (Cathartes aura). When I think of them, the reds and pinks of their mostly featherless heads spring to mind and how those colors contrast with the raptor’s black plumage. I also think of their white and black underwings, plainly visible as the large birds trace their trademark tilting circles in the sky. Studying the bird in profile, however, a few things are immediately obvious. First, that famous turkey vulture “black” isn’t very black; much of the raptor’s dark plumage is actually brown – chocolate and coffee – with areas of smokey indigo. Second, the white underwings that serve as clear identifiers in flight are not visible in profile; the only whitish color seen is the pale ivory of the bird’s beak. Third, the vibrant reds and muted violets of the bird’s famous bald pate may draw our eye, but they account for a relatively small percentage of the bird’s color. Having created the turkey vulture poster, I will forever “see” vultures in a new way. In fact, the Field Guide project has me seeing all birds differently, or at least thinking about how I see them differently! I think (and read) a lot about the evolution of plumage coloration in particular species as well as how that color is produced – a ballet of melanins, carotenoids, and feather structure – and how what we see when we admire, say, a robin, is quite distinct from what another robin sees….or what a fiery skipper butterfly sees.

I also get to dive deeper into taxonomic conversations and debates. One of the recent poster releases featured the Audubon’s subspecies of the yellow-rumped warbler, one “version” of a species that’s caused a lot of taxonomic hand-wringing over the last fifty years. First, it was considered multiple species. Then, those different species were reclassified as just one, comprising two to four subspecies. Next came a genus reassignment. Things still aren’t settled; ornithologists continue to argue about the yellow-rumped warbler’s classification. I’m more of a lumper than a splitter, so I’m happy with the current consensus: one species, the yellow-rumped warbler (Setophaga coronata), with two to four subspecies, most notably the Audubon’s warbler (Setophaga coronata auduboni) in western North America and the Myrtle warbler (Setophaga coronata coronata) in the east. No matter how we lump or split the species, though, English-speaking birders call them “butter butts” and often note their presence with ennui (“Oh, just some butter butts.”). That muted response is due to the warbler’s prevalence, but – wow! – the breeding male Audubon’s warbler cuts a rakish profile! Look at those bands of warm charcoal, cool slate and alabaster, and brilliant yellow. I can’t bring myself to call such a sharp-dressed guy a “butter butt,” so I’ll use the direct translation of the bird’s scientific binomial instead, “crowned moth eater.”

At last, in July 2021, after I’d created the first 17 posters, I officially announced Field Guide. As I put it at the time, the poster project had been gestating for years, hatched during the first year of the pandemic, and finally fledged. The resulting posters are visually compelling tributes to each featured species. Exhibited together, the posters can also be organized into a loose color taxonomy, providing an alternative, aestheticized approach to classifying or grouping these species. I hope that the Field Guide posters will be appreciated by bird nerds, designers, and lovers of artists like Josef Albers. In the four months since the project’s launch, I’ve received a lot of positive feedback. A number of artists and designers have responded to Field Guide with some variation of “I wish I’d thought of that”; that’s the highest praise you can receive from your creative peers. A few of my scrupulous scientist friends inquired about the process, wishing to “see my work”; I was both gratified and relieved when one described it as “maximally meticulous.” As of late November, I’ve learned of a number of bird and birder oriented publications (other than Golden Gate Bird Alliance) that wish to cover the series, as well.

At the time of writing, the Field Guide series now includes thirty-two birds, and I release another each week. If you have a special request, let me know and I’ll see what I can do! Per my charitable sales model, whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges.

Christopher Reiger’s childhood love of the outdoors evolved into a fascination with natural history, conservation, and ecology. His visual art, illustration, design, and writing projects wrestle with contemporary constructions of nature, and the human relationship to nonhuman animal species. Christopher lives in Santa Rosa with his wife and two young sons.

To check out and support Reiger’s Field Guide project and other work please visit his website here.