New SF program to prevent residential bird collisions

By Ilana DeBare

San Francisco already has one of the country’s first laws aimed at preventing bird-window collisions in new commercial buildings.

Now — with support from Golden Gate Bird Alliance — the city is taking aim at the problem of bird-window collisions in private residences too.

The City Planning Department is sponsoring a new, voluntary Bird-Friendly Monitoring and Certification Program that will:

- Recruit city residents to monitor the incidence of bird-window collisions around their home.

- Help residents with large or hazardous windows to take steps to reduce the risk of collisions.

“We are especially interested in residential properties because this is generally the land use that is found near our parks and open spaces, and where we expect more birds,” said Andrew Perry of the City Planning Department.

“So far, there hasn’t been enough scientific data gathered on bird-window collisions in urban residential settings,” said Cindy Margulis, Executive Director of Golden Gate Bird Alliance. “San Francisco’s new program will allow people to contribute to our understanding of an important conservation issue by doing very simple things right in their own backyard.”

Black-and-White Warbler at a window / Photo by allaboutbirds.org

Black-and-White Warbler at a window / Photo by allaboutbirds.org

San Francisco’s new monitoring program is seeking participants — especially people living near parks or open spaces — who will check the exterior of their home for dead or injured birds at least once a week. Participants will input their findings on a city web site, allowing city planners to develop data on the location and frequency of bird-window collisions.

In return, participants will receive a decal certifying them as a “Bird-friendly Resident.” They will be eligible for raffle prizes. More significantly, they can also seek city advice and subsidies in choosing a window treatment to decrease the risk of collisions.

Treatments to prevent collisions range from simple measures such as installing insect screens or hanging strings in front of large picture windows, to more sophisticated measures such as applying textured film over windows or completely replacing windows with fritted glass. The city will offer a limited number of subsidies to residents with hazardous windows larger than 24 square feet.

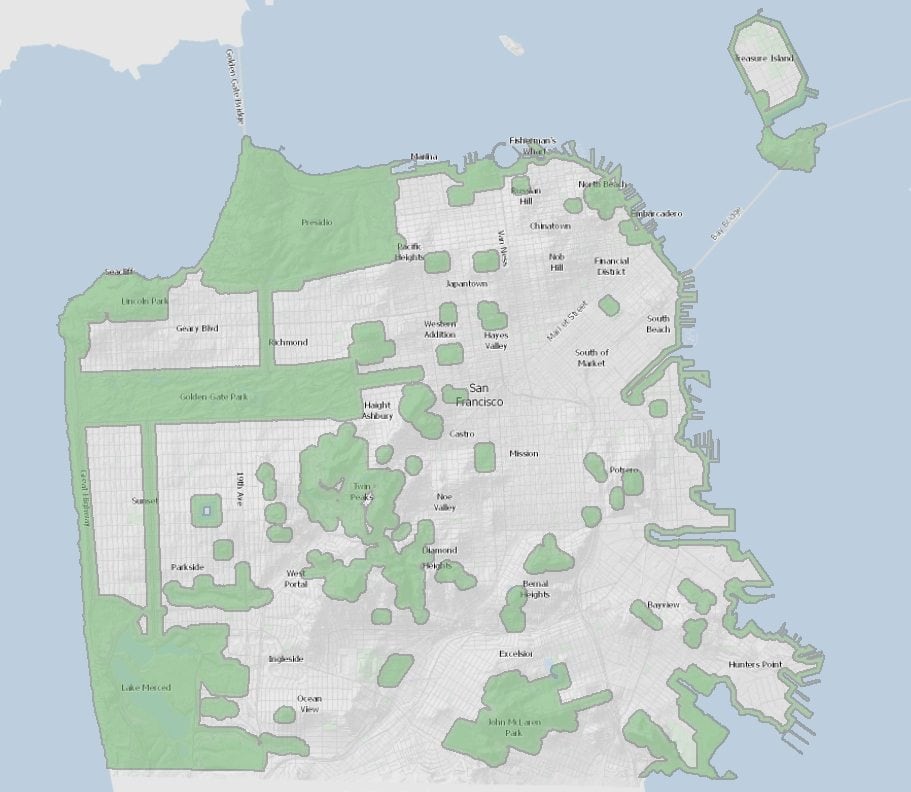

The SF monitoring program is open to all residents, but the city especially wants participants from the green areas on this map.

The SF monitoring program is open to all residents, but the city especially wants participants from the green areas on this map.

“We’ll work with homeowners on a case by case basis,” Perry said. “Because we’re focused on the design and feel of buildings, we don’t want to impose one treatment type for all buildings.…