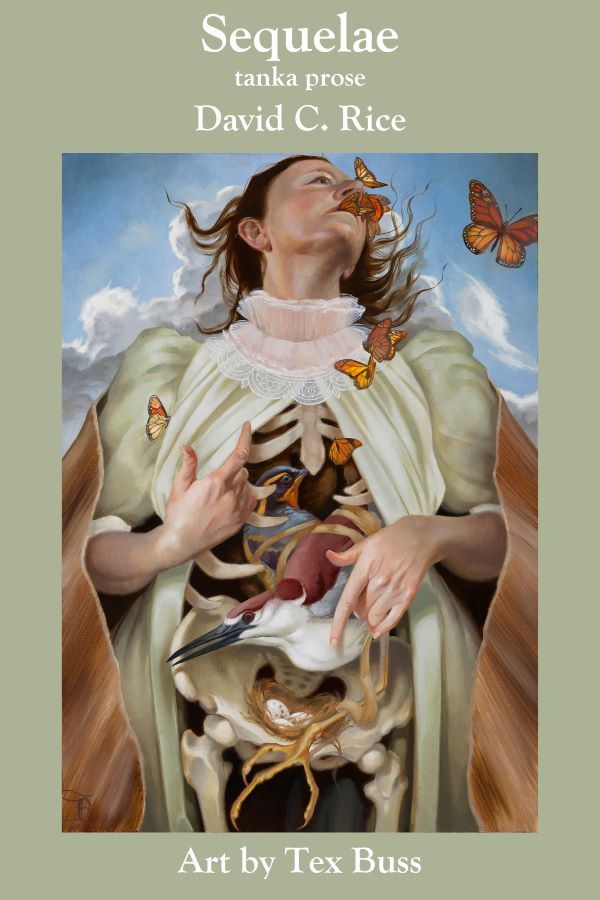

Sequela: Nature Poems in Response to Climate Crisis

by David Rice

Art by Tex Buss

Tanka is a lyrical poetic form written in Japan for the past twelve-hundred-plus years and by English-language poets for about a hundred years. It aims to crystallize emotional responses to specific perceptions and often includes a link-and-shift somewhere in its five lines.

dawn

three coyotes watch me

and a thrush sings

could be the last century

— we can’t go back

Adding prose allows the poet to expand the context of the short poem. I have written a tanka prose book, “Sequelae”, that looks at our responses to the climate crisis. Tex Buss’s painting is on the cover, and the book also includes nine of her bird paintings.

Room For Improvement

If we were to change our climate course, who would steer? The wealthiest five-percent, who use thirty-five percent of the carbon, are on cruise control. Those who lack resources are just trying to stay on the road. Can those of us in the middle grab the wheel and turn us off the super-sized highway?

a woodpecker hammers but

that telephone pole

is no longer a tree

how do we drill

beneath our daily routines?

Lost Bird: Reward

Mid-1950s, snow on the ground, and one morning a flock of Evening Grosbeaks in our backyard. The bird book promised warblers in spring. Back then, climate change was for geologists, extinction for dinosaurs.

the global thermometercardinal red

we’re goldfinch

so pleased with our song

we can’t stop

Money, fittest of all survivors, always flies. The oil barons could leave some in the ground, but depending on alpha predators to nurture their prey for the common good is a bad bet. Still, I’ve got to put my chips down . . . on green.

old jigsaw puzzle

a robin hidden

in a leafed-out oak

I must keep looking

for the lost piece

The book also contains four prose birding pieces.

I can close my eyes and see the Short-eared Owl perched on the standing four-foot, broken-off tree trunk in the middle of the meadow as twilight fades to night. Then it’s another year, and I see the full-moon-lit meadow, where magic is afoot and anything is possible.I’ve spent six months here, over a forty-year period, backpack camping at Snag Lake. These trips were Golden Gate Audubon Society birding trips I co-led with Robin Pulich. The tiny lodgepole pines have advanced on the meadow from the forest, and then have died when a heavy snow-melt year submerged the meadow in two feet of water.…

Shorebirds at Elsie Roemer – Rick Lewis

Shorebirds at Elsie Roemer – Rick Lewis Reusable Sandwich Bags

Reusable Sandwich Bags

Credit: Rulenumberone

Credit: Rulenumberone

Birding at a natural area near our home in Fort Collins, Colorado

Birding at a natural area near our home in Fort Collins, Colorado View from Golden Gate Overlook during a recent visit to San Francisco

View from Golden Gate Overlook during a recent visit to San Francisco