Viewing birds through their nests

San Francisco photographer Sharon Beals will be a guest exhibitor at our Birdathon Awards Dinner on Sunday May 19th. Sharon is the author of Nests: Fifty Nests and the Birds that Built Them, published by Chronicle Books. For the nests in her book, she turned to the collections of the California Academy of Sciences, the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, and the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. Join us at the Birdathon dinner to meet Sharon and see some more of her work! (Note: Registration deadline for the dinner is Tuesday May 7th.)

The following is an excerpt of an interview with Sharon Beals by Chuck Hagner, from BirdWatchingDaily.com.

——————————————

BirdWatching: Where did the idea for the book come from?

Beals: The idea evolved over a 10-year trajectory that began after reading Scott Weidensaul’s amazing book Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds. Besides explaining how birds manage to find their way — navigating by stars, magnetic fields, polarized light, or even what might be some inherited instinct — he also talks about what they encounter along the way, and at either end of these journeys.

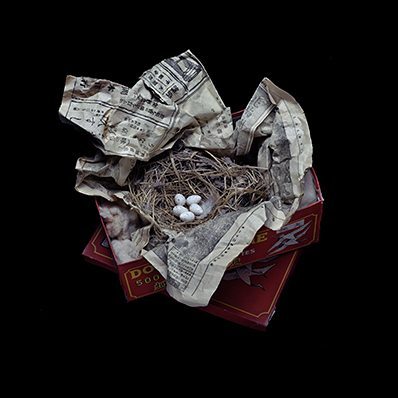

Pine Siskin nest / Photo by Sharon Beals

Pine Siskin nest / Photo by Sharon Beals

And as most of your readers may already know, migratory hazards and habitat loss are affecting so many birds around the world. I had already been interested in native plants and habitat restoration, but this book was the inspiration to learn as much as I could about what birds need to survive and about what I do in my own life that affects the welfare of birds, even at a distance.

BirdWatching: What made you ask, in 2007, to see the collection of nests and eggs at the California Academy of Sciences?

Beals: I wanted to share what I was learning, and to reach a larger audience than the already-converted choir of birders and native-plant aficionados. How to do that with my skill and artistry eluded me. It was only after photo-ing some of a friend’s innocently but, as it turned out, illegally collected nests (now either returned to the wild or donated to the Academy for use in nature education) that I felt that I had found a subject matter that would engage a wider public and, hopefully, engender their interest in birds.

California Towhee nest / Photo by Sharon Beals

California Towhee nest / Photo by Sharon Beals

BirdWatching: Are nests more of scientific or artistic interest to you?…