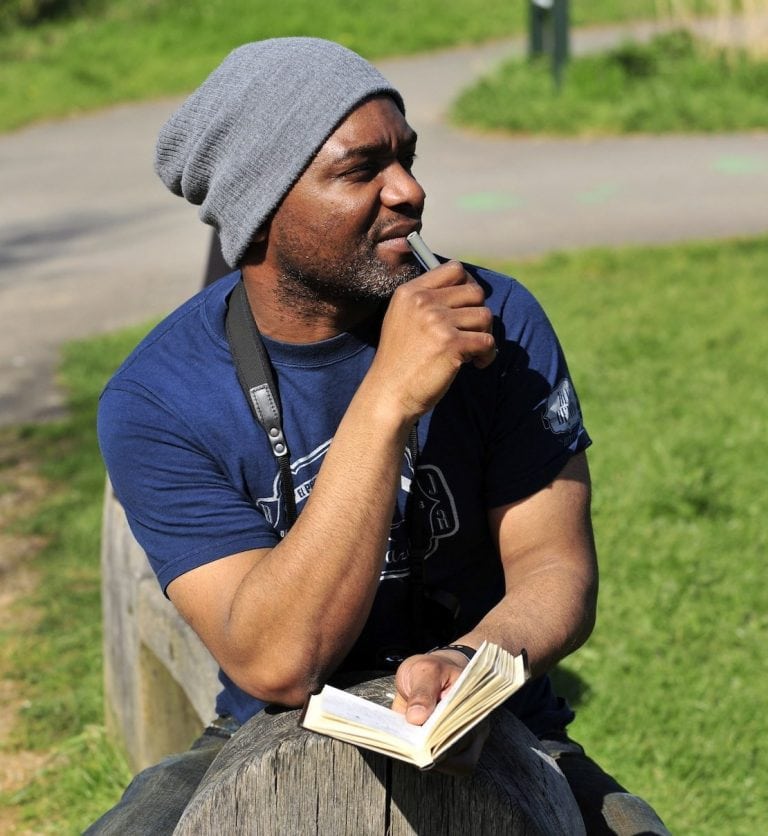

David Lindo, Urban Birder

By Ilana DeBare

As residents of San Francisco and the East Bay, we in Golden Gate Bird Alliance are all pretty much urban birders.

But David Lindo is The Urban Birder.

A native of London, Lindo has built a career around extolling the wonder of birding in cities. He’s done books, TV shows, tours and writes a blog called (of course) The Urban Birder.

“I’m all about trying to engage people who haven’t declared an interest in birds,” he said during his first visit to the Bay Area last week. “I see myself as a conduit, a gateway, a bridge. It’s all about looking up and realizing nature is all around us, not just on the TV or off in the countryside.”

When we learned that Lindo was visiting California, we got together with our partners at Outdoor Afro and hosted a small reception for him. We hope to sponsor him at a large public speaking event the next time he visits here.

David Lindo and Eagle Owl / Photo by Darren Crain

David Lindo and Eagle Owl / Photo by Darren Crain

Lindo, 49, walked an unlikely path to birding. He grew up in a working-class black and Irish neighborhood in North London where he knew no one with any interest in birds. But he was fascinated by wildlife from early childhood – a “twitcher in the womb,” as he puts it, using the British word for a highly competitive birder.

“I’d look around and decide that sparrows were ‘baby birds’ and starlings were ‘mommy birds.’ It wasn’t until I was around seven and went to the library that I knew what they were called. I read things voraciously. By the age of eight, I was a walking encyclopedia on the birds of Britain.”

Lindo’s first adult birding mentor was a foreman from his father’s factory who was an “egger” – a devotee of a British pastime, popular in Victorian times but now vilified by conservationists, of collecting eggs out of nests.

“Luckily I wsn’t contaminated with the egg collecting gene,” he joked.

Lindo uses his race, enthusiasm and humor to break down British stereotypes of birders. “In Britain a lot of people have the impression that birders are male, big-bellied and white – dull people,” he said. “I break that stereotype in many ways. People think that birds are geeky or for nerds, but then they hang out with me and realize it is quite fun and contemporary.”…