Audubon birders in Nome, Alaska

By Carol and Steve Lombardi

If you’ve only seen Nome as the snow-covered finish line for the Iditarod, well — as Madeline Kahn sang, “You’d be surprised…”

At about 9 p.m. on a June evening, we stepped down from our third aircraft of the day into the pleasantly brisk Nome twilight. Green grass bordered the airfield, interrupted by small patches of snow. A short drive around the city and harbor started our trip list with Red-Throated Loon, Red-Necked Grebe, Long-Tailed Jaeger, Slaty-Backed Gull, Common Redpoll, Red-Necked Phalarope, and — in someone’s backyard — a few musk oxen. Our modest motel was located at the Iditarod finish line on the shore of the Norton Sound, which was smooth as glass.

We were in Nome on a birding trip sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance. Our guide, Rich Cimino of Yellowbilled Tours, uses the extended daylight of “the land of the midnight sun” to provide an intense three-day birding experience. The birds are active both day and “night,” and so were we. We saw about 90 species and got 15 life birds.

Willow Ptarmigan / Photo by Rich Cimino

Willow Ptarmigan / Photo by Rich Cimino

For a couple of Bay Area birders like ourselves who are used to seeing shorebirds on the shore, it seemed odd to see shorebirds nesting well inland in shrubs (Western Sandpiper) or on an airstrip (Ruddy Turnstone).

Nome is a frontier town built to survive the winter: It’s a mere 100 miles south of the Arctic Circle. Structures have few windows — they’re inefficient in the cold — and the tallest building is the new four-story hospital.

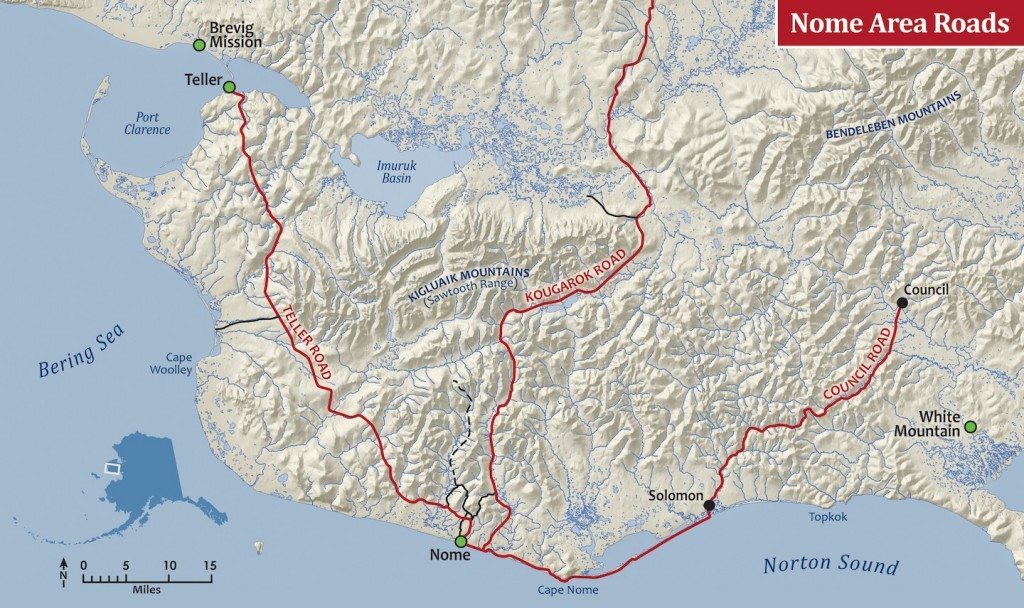

Because you must fly or barge everything in or out of Nome (there are no roads connecting to the outside world), the environmentalist comment that you never really throw anything away is vividly illustrated here. Industrial trash — trucks, buildings, machinery — stays where it stopped. And with a year-round population of only 3,700, it’s not hard to get out into nature. The “suburbs” are a 15-minute drive from the main street of the town.

View of Nome, the Norton Sound and musk oxen in the foreground / Photo by Steve Lombardi

View of Nome, the Norton Sound and musk oxen in the foreground / Photo by Steve Lombardi

Nome and area / Courtesy of Alaska Dept. of Fish & Game

Nome and area / Courtesy of Alaska Dept. of Fish & Game

On Day 1 we drove southeast along Council Road in a warm, comfy pickup. The drive started along the beach and lagoons—finding Brant and Cackling Goose, Common Eider and Harlequin Duck, Lapland Longspur, Black-Legged Kittiwakes, Arctic Tern, Red-Throated Loon, and Yellow Wagtail.…