A 2014 resolution – buy shade-grown coffee

By Scott Weidensaul

Migratory birds—which must overcome so many natural challenges as they journey from one end of the globe to another—are having a much harder time overcoming the obstacles that humans have added to the mix: habitat loss, environmental contaminants, climate change, and a lot more.

But we humans can be helpful, too. I saw vivid proof of that last January in the highlands of northern Nicaragua, where declining migrants such as Wood Thrushes spend the nonbreeding season. For years, this area has been a stronghold for farmers growing quality shade coffee. Not coincidentally, it’s also known as a paradise for birds.

An island of fertile green

Everywhere we looked, we saw migrants: Philadelphia, Warbling, and Yellow-throated Vireos; Tennessee, Chestnut-sided, Wilson’s, and Yellow Warblers rolling through the understory in constant, flickering motion; Western Kingbirds and Western Wood-Pewees hawking insects in the treetops; Summer Tanagers and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks mixing with resident species like Black-headed Saltators and Clay-colored Robins. Flocks of Baltimore Orioles descended on blossoming trees and plucked the brilliant yellow flowers, dropping showers of blooms as they drank the rich pockets of nectar they’d revealed.

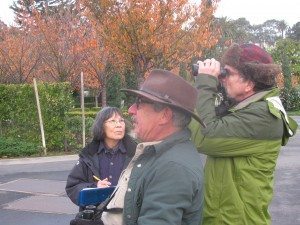

The highlands of northern Nicaragua, a productive shade coffee-growing region and refuge for migratory birds in winter. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

The highlands of northern Nicaragua, a productive shade coffee-growing region and refuge for migratory birds in winter. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

Rose-breasted Grosbeak / Photo by Bob Lewis

Rose-breasted Grosbeak / Photo by Bob Lewis

Later, in the village of San Juan del Río Coco, I met with members of a cooperative of more than 400 small coffee producers who raise more than 2.5 million pounds of shade coffee every year. These producers raise coffee the way it’s been farmed for centuries there, below the canopy of intact, functioning forests that provide critical habitat for scores of migratory bird species. When these shade coffee farmers prosper, the outlook for migratory birds gets brighter, too.

Seen from space, though, the hills around San Juan del Río Coco are an island of fertile green surrounded by hundreds of square kilometers of land already converted to sun coffee, pasture, and grain fields.

The fertile hills around Nicaragua’s San Juan del Río Coco are surrounded by denuded landscapes like this one—former forests converted to sun coffee, pasture, and grain fields. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

The fertile hills around Nicaragua’s San Juan del Río Coco are surrounded by denuded landscapes like this one—former forests converted to sun coffee, pasture, and grain fields. Photo by Scott Weidensaul.

Increasingly, small shade coffee farms have been destroyed to make way for sun-tolerant coffee—an industrialized, chemical-dependent system that renders what had been prime bird habitat into the ecological equivalent of a parking lot. By some estimates, more than 40 percent of the shade coffee farms in Latin America have already been lost to satiate the demand for cheap coffee.…