James Bond, birder

By Ilana DeBare

You’d never guess it from the box-office-blockbuster Skyfall, but…

James Bond was a birder.

No, not the Daniel Craig, Pierce Brosnan, Sean Connery secret agent Bond. But the James Bond who was an eminent American ornithologist, an expert in Caribbean birds who wrote the definitive Birds of the West Indies field guide.

In fact, Ian Fleming named his secret-agent-Bond after the birder.

Wikipedia writes:

Ian Fleming, who was a keen bird watcher living in Jamaica, was familiar with Bond’s book, and chose the name of its author for the hero of Casino Royale in 1953, apparently because he wanted a name that sounded ‘as ordinary as possible’. Fleming wrote to the real Bond’s wife, “It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born.”

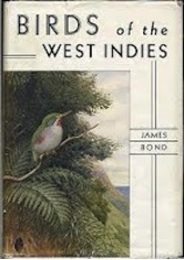

Birds of the West Indies by James Bond, 1936 edition

Birds of the West Indies by James Bond, 1936 edition

Fleming initially used Bond’s name without permission, according to a 2008 article by Katherine Tweed in Audubon magazine. Apparently Bond didn’t notice until several years had passed — at which point his wife wrote a furious letter to Fleming. The novelist apologized and said he viewed Bond’s field guide as “one of my bibles.” He later invited the Bonds to stay at his Jamaican estate.

The real Bond was born in Philadelphia in 1900. His interest in natural history grew out of a trip taken by his father to the Amazon in 1911. Later he studied at Cambridge University, worked briefly as a banker, and then joined the staff of Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, eventually becoming its curator of birds.

Since Bond first published his Birds of the West Indies in 1936, it has been reissued several times, including as a Peterson Guide. Bond died in Philadelphia in 1989.

Wikipedia notes that, “In his novel Dr. No, Fleming referenced Bond’s work by basing a large Ornithological Sanctuary on Dr. No’s island in the Bahamas.”

In the 2002 Bond film Die Another Day, the Pierce-Brosnan-Bond is seen examining Birds of the West Indies in an early scene that takes place in Cuba.

Later in that film, Brosnan introduces himself to the Halle Berry character as an ornithologist. It was, of course, a false identity.

But not quite as false as most movie viewers assumed.

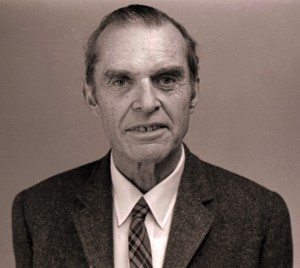

James Bond, birder, 1974 / Photo by Jerry Freilich from Wikimedia Commons…

James Bond, birder, 1974 / Photo by Jerry Freilich from Wikimedia Commons…