“Notable” nature discoveries at all ages

By Anthony DeCicco

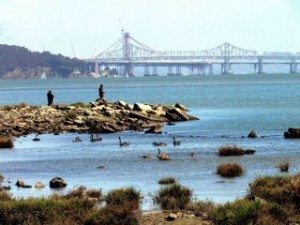

With the school year ending, it was time for me to write up the annual summary of Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s Eco-Education Program, in which we lead kids and families from twelve low-income elementary schools in discovering nature and wildlife.

The past year included 50 weekday field trips to local wetland and riparian habitats, over ten family trips to Muir Beach and Alcatraz, and 30 expeditions surveying living organisms in schoolyards. As I catalogued the outcomes, I found myself stumbling over the phrase “notable discoveries.”

“Notable to whom?” I wondered. To the eco-adults reading the report, or to our urban students out in the field for the first and perhaps only time all year?

If the latter, then “notable discoveries” would surely include the burnt-orange breast of an American Robin… the mohawk atop a Stellar’s Jay… a jackpot of scurrying shorecrabs as kids turned over a mudflat rock… a two-inch Jerusalem cricket (aka Niña de la Tierra) crawling across the path… or a newly hatched Western Gull.

Eco-Ed class viewing cormorants on Alcatraz / Photo by Anthony DeCicco

Eco-Ed class viewing cormorants on Alcatraz / Photo by Anthony DeCicco

And what about my own personal epiphanies for the year, the moments when I yelled in excitement either to the kids or to myself?

Those included:

- Seed shrimp swimming in the vernal pools near the abandoned parking lot of Merritt College in Oakland.

- Bright orange scuds (freshwater amphipods) at the headwaters of Islais Creek in Glen Canyon.

- 2×2 inch, paper-thin flatworms undulating along the underside of a rock along the Point Pinole Shoreline.

- A lone Wilson’s Phalarope that landed near me in the waters at Pier 94 and began to forage so elegantly. (YES!)

Other thrilling moments shared by both adults and students were when a burrowing owl and an American crow engaged in an aerial battle above Paul Revere Elementary in Bernal Heights… when a damselfly along Islais Creek emerged from its nymph-shaped exoskeleton… and when we collected a mystery species of gunnel fish from under a rock along the tides at Pier 94 and mistakenly screamed “eel!” as we watched its body wriggle in our container.

Then what about the time on an Alcatraz family trip when I was passionately proclaiming to a participating father the fascinating traits of a Brandt’s Cormorant – its streamlined swim-friendly body, its ability to dive 100 feet when fishing, its bright blue throat for courtship display?

Eco-Ed students with soaproot, a native plant used by Native Americans as a fish poison, an antiseptic and a glue / Photo by Anthony DeCicco

Eco-Ed students with soaproot, a native plant used by Native Americans as a fish poison, an antiseptic and a glue / Photo by Anthony DeCicco

No reaction.…