By Ryan Nakano and Jeni Schmedding

.kb-image66786_4d0d86-db .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}.kb-image66786_4d0d86-db img.kb-img, .kb-image66786_4d0d86-db .kb-img img{object-position:55.00000000000001% 13%;}

Ridgway’s Rail / Rachel Lawrence

As the sky awakens at Meeker Slough, a beautiful array of colors backdrop the channeled saltwater marsh. The morning calls and the elusive and endangered Ridgway’s Rail respond with a round of applause, “Kek kek kek kek” as if to acknowledge each new dawn as nothing short of a miracle.

And in many ways it is a miracle for these olive-brown and cinnamon-colored hen-sized birds, skulking and skittering about, probing the mudflats with their lean orange beaks.

“Right here, where the bay meets the land and these tidal wetlands occur, that’s where the Ridgway’s Rails live and thrive,” wildlife biologist and Ridgways Rail Monitoring Manager Jen McBroom said. “Unfortunately, we’ve lost 85% of our tidal wetlands in the bay since we started developing these shoreline habitats.”

.kb-image66786_cf317c-3f .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}

Ridgway’s Rail at Meeker Slough / Alan Krakauer

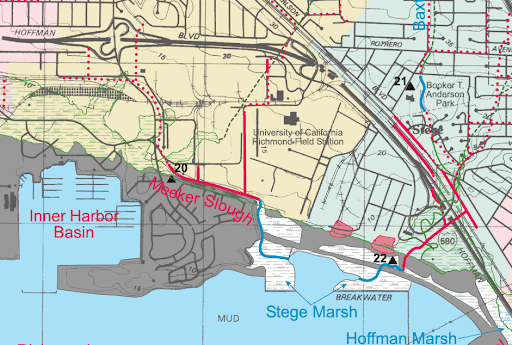

McBroom, who’s been officially monitoring the Ridgway’s Rail population with Olofson Environmental Inc. for the past decade, detected 17 rails in total with her team during this year’s most recent survey, making Meeker Slough and neighboring Stege Marsh, one of the densest Ridgways Rail habitat in the Bay Area.

.kb-image66786_c99150-35.kb-image-is-ratio-size, .kb-image66786_c99150-35 .kb-image-is-ratio-size{max-width:664px;width:100%;}.wp-block-kadence-column .kt-inside-inner-col .kb-image66786_c99150-35.kb-image-is-ratio-size, .wp-block-kadence-column .kt-inside-inner-col .kb-image66786_c99150-35 .kb-image-is-ratio-size{align-self:unset;}.kb-image66786_c99150-35{max-width:664px;}.image-is-svg.kb-image66786_c99150-35{-webkit-flex:0 1 100%;flex:0 1 100%;}.image-is-svg.kb-image66786_c99150-35 img{width:100%;}.kb-image66786_c99150-35 .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}

Map of Ridgway’s Rail observations in 2023 California Ridgway’s Rail Surveys for the San Francisco Estuary Invasive Spartina Project by Olofsen Environmental Inc.

.kb-image66786_a2f696-11.kb-image-is-ratio-size, .kb-image66786_a2f696-11 .kb-image-is-ratio-size{max-width:668px;width:100%;}.wp-block-kadence-column .kt-inside-inner-col .kb-image66786_a2f696-11.kb-image-is-ratio-size, .wp-block-kadence-column .kt-inside-inner-col .kb-image66786_a2f696-11 .kb-image-is-ratio-size{align-self:unset;}.kb-image66786_a2f696-11{max-width:668px;}.image-is-svg.kb-image66786_a2f696-11{-webkit-flex:0 1 100%;flex:0 1 100%;}.image-is-svg.kb-image66786_a2f696-11 img{width:100%;}.kb-image66786_a2f696-11 .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}

Map from UC Berkeley Richmond Field Station

For this reason, among many others, Meeker Slough on the southend of the Richmond shoreline, is a critically important place to protect, a place full of promise, full of hope, and unfortunately, full of trash.

.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-column-wrap{align-content:start;}:where(.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-column-wrap) .wp-block-kadence-column{justify-content:start;}.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-column-wrap{column-gap:var(--global-kb-gap-md, 2rem);row-gap:var(--global-kb-gap-md, 2rem);padding-top:var(--global-kb-spacing-sm, 1.5rem);padding-bottom:var(--global-kb-spacing-sm, 1.5rem);grid-template-columns:repeat(2, minmax(0, 1fr));}.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-layout-overlay{opacity:0.30;}@media all and (max-width: 1024px){.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-column-wrap{grid-template-columns:repeat(2, minmax(0, 1fr));}}@media all and (max-width: 767px){.kb-row-layout-id66786_71f4f9-81 .kt-row-column-wrap{grid-template-columns:minmax(0, 1fr);}}

.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col,.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col:before{border-top-left-radius:0px;border-top-right-radius:0px;border-bottom-right-radius:0px;border-bottom-left-radius:0px;}.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col{column-gap:var(--global-kb-gap-sm, 1rem);}.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;}.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col .aligncenter{width:100%;}.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col:before{opacity:0.3;}.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d{position:relative;}@media all and (max-width: 1024px){.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;justify-content:center;}}@media all and (max-width: 767px){.kadence-column66786_47cbbc-7d .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;justify-content:center;}}

.kb-image66786_fc7ef7-11 .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}

Ridgway’s Rail in tire at Meeker Slough / Rick Lewis

.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col,.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col:before{border-top-left-radius:0px;border-top-right-radius:0px;border-bottom-right-radius:0px;border-bottom-left-radius:0px;}.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col{column-gap:var(--global-kb-gap-sm, 1rem);}.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;}.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col .aligncenter{width:100%;}.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col:before{opacity:0.3;}.kadence-column66786_037cda-59{position:relative;}@media all and (max-width: 1024px){.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;justify-content:center;}}@media all and (max-width: 767px){.kadence-column66786_037cda-59 .kt-inside-inner-col{flex-direction:column;justify-content:center;}}

.kb-image66786_78eba4-93 .kb-image-has-overlay:after{opacity:0.3;}

Shopping carts and other debris in Meeker Slough / Jeni Schmedding

Among the rails, ducks, herons, and other wildlife, and below steady streams of cyclists, joggers, and dog walkers on the SF Bay trail, sit large truck tires, half-submerged shopping carts, and all matter of junk in the mudflats past the slough’s perimeter fence. …

Photo provided Audubon California

Photo provided Audubon California

Hairy Woodpecker by Whitney Grover

Hairy Woodpecker by Whitney Grover

Trip leaders Dan Scali (left) and Jeanette Pettibone (right) with new birders from LightHouse. Photo @ Helen Doyle

Trip leaders Dan Scali (left) and Jeanette Pettibone (right) with new birders from LightHouse. Photo @ Helen Doyle