Birdathon 2021: Soaring success

By Ilana DeBare

If Birdathon 2021 were a film, we’d say “it’s a wrap!”

Instead we’ll say, “it’s a rap-tor!”

Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s annual fundraiser came to a high-flying conclusion over the weekend, capping two months of innovative new events designed to carry on despite Covid.

Unable to hold our usual in-person Birdathon programs, our creative volunteers came up with three alternatives: a series of ten Virtual Field Trips via Zoom, a socially distanced Christmas-in-May Bird Count, and an online Birdathon Adventure Auction. They culminated with a Birdathon Virtual Celebration on Sunday night.

These new events were highly successful in all respects—number of participants, quality of the experiences, and funds raised. Here’s a flyover raptor’s-eye view of them all.

White-tailed Kite during the Oakland Christmas-in-May Bird Count, by Mark Rauzon

White-tailed Kite during the Oakland Christmas-in-May Bird Count, by Mark Rauzon

Virtual Field Trips

We sponsored ten Zoom “trips” that ranged from viewing Sage-Grouse in Lassen County to a pelagic journey to the Farallones. Over 400 people signed up and attended an average of two trips each. We raised $13,200, or more than $1,000 per trip.

Bonus: Video recordings of all the Virtual Field Trips are available, so you can watch any that you missed! View descriptions of the trips here. Then call our office at (510) 843-2222 to provide credit card payment of $15 per trip and get the link to the recording. The best time to call is on Mondays through Thursdays, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Christmas-in-May Bird Count

Over 140 people signed up for counts in Oakland and San Francisco that coincided with eBird’s Global Big Day on Saturday, May 8th. We managed to cover most of our regular Christmas Bird Count areas, and enjoyed sightings of breeding birds as well as balmy temperatures that aren’t available in December. Oakland count participants got to try out some new features—paperless reporting, using only eBird, plus new digital maps—that will prove useful in future Christmas Bird Counts.

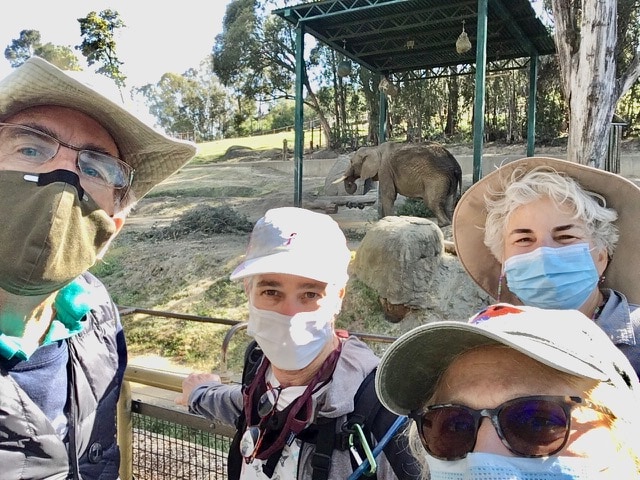

Christmas-in-May Count at the Oakland Zoo / Photo courtesy of Mark Rauzon

Christmas-in-May Count at the Oakland Zoo / Photo courtesy of Mark Rauzon

Barn Owl during Christmas-in-May Bird Count by David Assmann

Barn Owl during Christmas-in-May Bird Count by David Assmann

Registration fees generated a total of $3,260; one generous member covered fees for people who found them a challenge. Special thanks to count compilers Dawn Lemoine and Viviana Wolinsky (Oakland) and David Assmann and Siobhan Ruck (San Francisco) for creating this successful new event from scratch.

Birdathon Adventure Auction

The online auction, which closed Sunday night, brought in more than $15,000 for Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s conservation and education programs!…

View of Toms Point / Photo by Dan Gluesenkamp

View of Toms Point / Photo by Dan Gluesenkamp

Aerial view of Toms Point showing various habitats—dunes, marsh, grasslands / Courtesy of Dan Gluesenkamp

Aerial view of Toms Point showing various habitats—dunes, marsh, grasslands / Courtesy of Dan Gluesenkamp

Ephemeral dune wildflowers, including Cammasonia and rare Gilia

Ephemeral dune wildflowers, including Cammasonia and rare Gilia

Coastal scrub habitat at Tom’s Point / Photo by Dan Gluesenkamp

Coastal scrub habitat at Tom’s Point / Photo by Dan Gluesenkamp

1: A few felted friends. Photo by Hilary Powers

1: A few felted friends. Photo by Hilary Powers

An inviting trail in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve. But further along will it hold roadblocks for birders with mobility challenges? Photo by Emily Wheeler.

An inviting trail in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve. But further along will it hold roadblocks for birders with mobility challenges? Photo by Emily Wheeler.