Palm Springs and the Salton Sea: Reflections

By Marjorie Powell

If you’d like to begin planning your 2021 outings or want to jump-start next year’s eBird list, consider joining the GGBA birding trip to Palm Springs and the Salton Sea, by Nature Trip. This past January, eight birders (including me!) joined the two guides, Eddie Bartley and Noreen Weeden, to look for birds in this area east of Los Angeles. Eddie and Noreen planned 5 days of birding, including the afternoon of our arrival day and the morning of our departure day.

We visited varied habitats, upland forest, desert, shoreline, and saw many of the birds that nest there, or visit for all or part of the winter, as well as one rarity. Several of us saw life birds during the week.

California Gulls and Bonaparte’s Gulls on the waterway. Photo by Noreen Weeden

California Gulls and Bonaparte’s Gulls on the waterway. Photo by Noreen Weeden

The Salton Sea is California’s largest inland lake and one of the important saline lake ecosystems, supporting large portions of some bird species in the winter. Audubon California is heavily involved in efforts to restore habitat and improve the environment at and around the Salton Sea for birds and humans.

As the Sea gets less and less water from the Colorado River and agricultural run-off, the lake is drying up and getting saltier. It’s now too salty to support many fish, so fewer fish-eating birds like American White Pelicans winter there. Currently bird species that eat insects that can survive in saltier water, such as Bonaparte’s Gulls, are wintering at the Sea. As marshlands at the edge of the Sea are created or restored, they support increasing numbers of birds for all or a portion of the winter and in migration.

Bonaparte’s Gulls by Harley Mac

Bonaparte’s Gulls by Harley Mac

Eddie Bartley, of Nature Trip, described how they came to run this tour for GGBA: “We began visiting Palm Springs area in the late 80s when a friend moved there, then a couple of more friends moved to Joshua Tree in the late ‘90s. Soon we were going each winter for a week or two to visit and bird -especially the Sea. We did several birding tours for out of state and international Nature Trip guests and quite a few Bay Area friends asked about birding down there so, starting about 2014 we offered GGBA field trips in non-consecutive years. It was long way to go for folks for a few days though so we would share a list of favorite places and routes.…

Photo by Bridget Cogley

Photo by Bridget Cogley

American Crow by Lonnie P.

American Crow by Lonnie P.

Crow by Eric Anderson

Crow by Eric Anderson

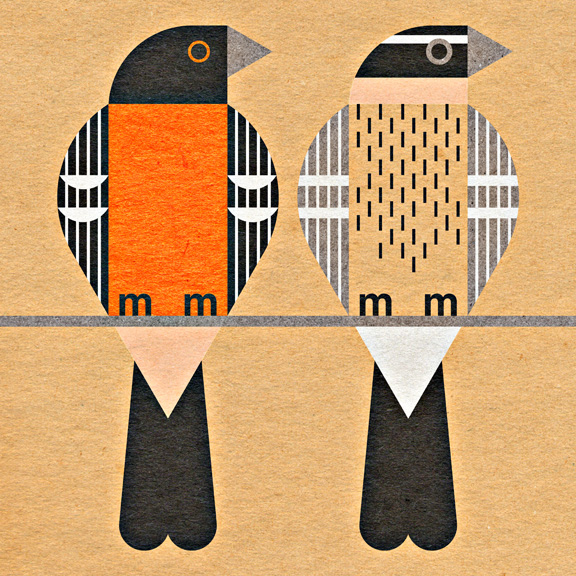

Black-headed Grosbeaks by Scott.

Black-headed Grosbeaks by Scott.

California Quail and Poppies by Molly

California Quail and Poppies by Molly