Bird Passports: A Collaboration

Text and photos by Alisa Golden

Editor’s Note: This blog originally posted at https://makinghandmadebooks.blogspot.com/2019/04/new-collaboration-letters-of-transit.html

I met Dianne Ayres through the Live Chat group that accompanies GGBA’s Osprey nest camera at sfbayospreys.org. Also known affectionately as the WWOC, it has been a community of people with a sense of humor who want to learn, and a place for kind people who care both about birds and about one another. Dianne and I met in person at a GGBA chalk art event where she was drawing a Red-tailed Hawk, and we got to talking. Our love for the Ospreys and

our mutual interest in textiles propelled us on to weekly walks by San Francisco Bay, where we scanned the sky, slough, and bay for birds to watch and photograph.

Richmond and Rosie, March 27, 2019

Richmond and Rosie, March 27, 2019

A book art call for entries that suggested both stitching and collaboration was the catalyst for long talks about how we might do a project together. Book art generally features a combination of art, text, and object, creating a tactile reading experience where all the parts communicate together. What could we make?

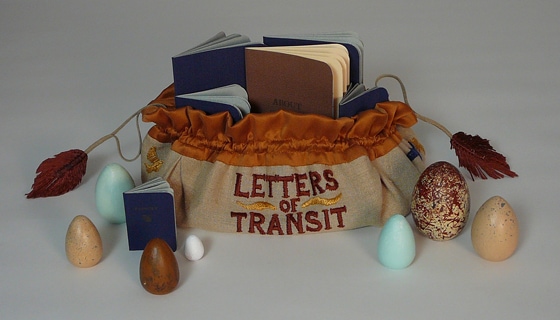

On our walks we began noticing migration patterns, how some birds were here for a specific period of time, how others were here year-round. We wondered where the birds came from and where they went. At the same time, U.S. borders were becoming tougher for human beings to cross, so migration was on our minds from all angles and emotions. Migration is a mixed bag as it is, carrying the risk of an arduous journey in the hopes of finding a home and freedom. Birds as a group have that freedom of crossing (unless humans mess it up). Bird passports evoke a record of their life paths. We researched some of the birds we had seen and designed visa stamps. How could we also portray their individual natures? Eggs could represent individual beings. Consulting the nest and egg books I got last year for my birthday: Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds and A Field Guide to Western Birds’ Nests, I painted wooden eggs.

Top (L to R): Osprey, Black Oystercatcher, Mallard Bottom (L to R): Green Heron, White-tailed Kite, Anna’s Hummingbird, American Coot

Top (L to R): Osprey, Black Oystercatcher, Mallard Bottom (L to R): Green Heron, White-tailed Kite, Anna’s Hummingbird, American Coot

We read that certain bird behaviors are embedded, but certain human actions can adversely impact the birds, confusing or changing the environment on which they rely: water, air, and earth.…

A beautiful day in Pinnacles National Park

A beautiful day in Pinnacles National Park

Bush poppies (Dendromecon rigida)

Bush poppies (Dendromecon rigida)

Streambank springbeauty (Claytonia parviflora)

Streambank springbeauty (Claytonia parviflora)