Celebrating our Centennial at Lindsay

By Ilana DeBare

Talk about grand finales! Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s traveling Centennial exhibit arrived at its final venue of 2017 this month – Lindsay Wildlife Experience in Walnut Creek – and looked like it had been designed to fit that exact space.

Over 150 GGBA members and friends gathered to launch the exhibit on Sunday, October 15, a beautiful afternoon that came after the week of terrible North Bay wildfires.

They were welcomed by Lindsay’s expert wildlife rehabilitation volunteers offering close-up views of some of their live, rescued birds, including a Northern Barred Owl and Great Grey Owl.

Attendees then browsed the colorful 14-panel exhibit on GGBA and its accomplishments, along with a display of striking taxidermied birds from the Lindsay collection. Kudos to GGBA staffmember Clay Anderson for hanging the taxidermied specimens so beautifully!

The Centennial exhibit fit beautifully in Lidnsay’s downstairs space. Photo by Ilana DeBare

The Centennial exhibit fit beautifully in Lidnsay’s downstairs space. Photo by Ilana DeBare

Belted Kingfisher from the Lindsay taxidermy collection / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Belted Kingfisher from the Lindsay taxidermy collection / Photo by Ilana DeBare

GGBA board member Jill Weader O’Brien and Lindsay Wildlife board member Elizabeth McWhorter welcomed the crowd, as did Ariana Rickard, representing Mount Diablo Audubon Society, which serves the Walnut Creek area. Then GGBA Executive Dirctor Cindy Margulis gave a passionate summary of the importance of GGBA’s work – made even more salient by events like the recent fires that put the people, landscapes, and wildlife of Northern California at risk.

Of course there was a 100th birthday cake, frosted with images of some of the species that GGBA has protected over the years: Western Snowy Plover, California Least Tern, Black Oystercatcher, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Burrowing Owl. (So some members went home able to make the unusual claim, “I ate a Burrowing Owl.”)

Happy 100th bird-day! Photo by Ilana DeBare

Happy 100th bird-day! Photo by Ilana DeBare

Some of the attendees at the Centennial launch reception at Lindsay Wildlife Experience. Photo by Ilana DeBare.

Some of the attendees at the Centennial launch reception at Lindsay Wildlife Experience. Photo by Ilana DeBare.

If you couldn’t attend the launch party, you can still enjoy and take part in the Centennial!

- An anonymous donor has offered $10,000 in matching funds for GGBA in honor of the Centennial. To help achieve this match, we need your tax-deductible donation by October 31st. Click here to give easily and securely online, or send a check to Golden Gate Bird Alliance, Attn: Centennial Match, 2530 San Pablo Avenue, Suite G, Berkeley CA 94702.

- Come visit the exhibit at Lindsay! It will be on display in two areas of the museum — upstairs in the Buckeye Room and also on the lower level– through February 2018.

This artist’s rendering of Archeopteryx shows how much it may have resembled our modern birds. / By Nobu Tamara via Wikipedia.

This artist’s rendering of Archeopteryx shows how much it may have resembled our modern birds. / By Nobu Tamara via Wikipedia.

The pier and the oystercatcher family / Photo by Tim Tindol

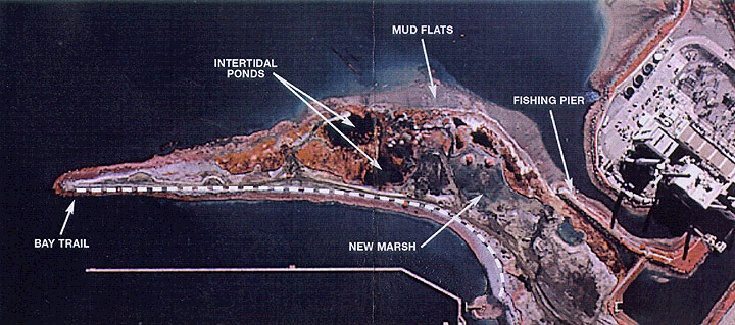

The pier and the oystercatcher family / Photo by Tim Tindol Heron’s Head Park viewed from the air, showing how it got its name. Lashlighter Basin is the water below (north of) the Bay Trail

Heron’s Head Park viewed from the air, showing how it got its name. Lashlighter Basin is the water below (north of) the Bay Trail

Views from the McCosker Loop Trail, which covers some of the Gateway Valley land that has been preserved from development. Photo by William Hudson

Views from the McCosker Loop Trail, which covers some of the Gateway Valley land that has been preserved from development. Photo by William Hudson

Ocean Beach in 2010, with virtually no beach left / Photo by Bill McLaughlin

Ocean Beach in 2010, with virtually no beach left / Photo by Bill McLaughlin Rock revetment covering Bank Swallow nesting sites at Ocean beach. Photo by Bill McLaughlin.

Rock revetment covering Bank Swallow nesting sites at Ocean beach. Photo by Bill McLaughlin.