From bird lover to bird lobbyist (for a day)

By Janet McGarry

Like most nature lovers, I am alarmed and outraged at Trump’s efforts to dismantle environmental regulations and policies. So when I read on Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s Facebook page about Audubon California’s Advocacy Day on June 8th, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to take action rather than despair and rage. Spending a day in Sacramento would be a small sacrifice in light of how much I love birdwatching and enjoy Audubon classes, walks, and lectures. I had traveled much further to attend the climate change conferences in Copenhagen and Cancun; a trip to Sacramento would be easy in comparison.

I was a bit nervous at the prospect of speaking to politicians, so was relieved when Audubon California invited me to participate in two conference calls to prepare for Advocacy Day. During the calls, Policy Director Mike Lynes provided background about the bills and advice about how to best communicate with legislators. Although they meet with many professional lobbyists, lawmakers are particularly interested in hearing about issues that impact their constituents. He encouraged us to speak about out personal experiences with birds in addition to the proposed legislation. He also reassured us that an Audubon employee knowledgeable about the bills would accompany each group of advocates.

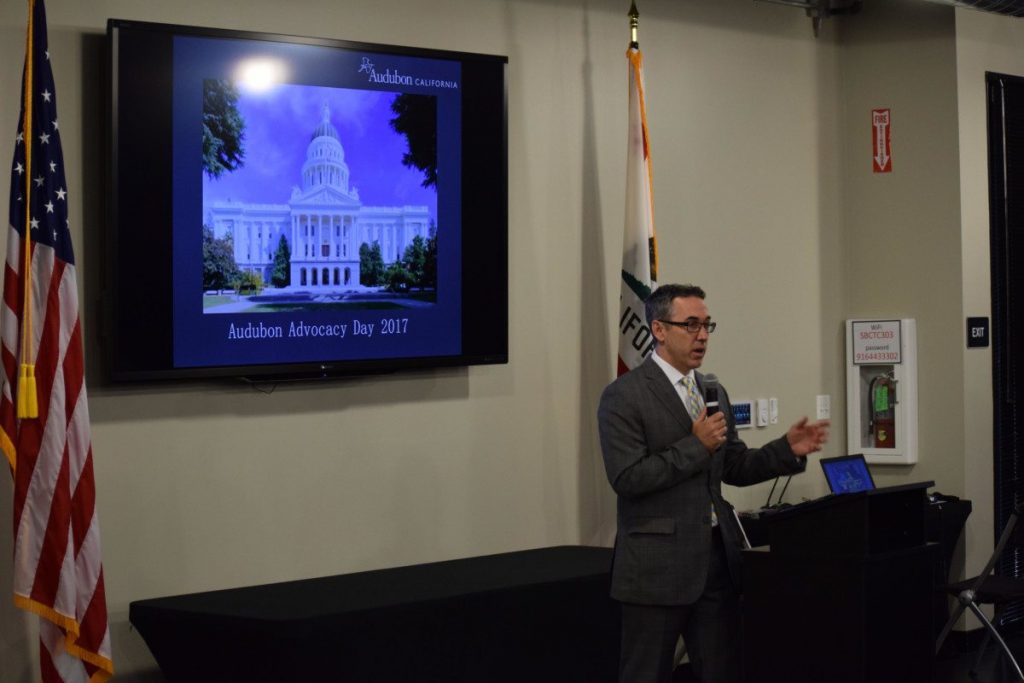

Mike Lynes orients the citizen-advocates at the start of the day. Photo by Chris Winn.

Mike Lynes orients the citizen-advocates at the start of the day. Photo by Chris Winn.

In addition to these training calls, Audubon staff scheduled meetings with legislators, helped coordinate carpooling, and provided links to web sites with information about legislators’ voting records. Some quick Internet research allayed any remaining anxiety: My representatives strongly supported environmental laws, so I anticipated “preaching to the choir” on Advocacy Day.

For our 2017 visits, Audubon focused on four areas that directly pertain to birds:

- Protecting California’s natural resources.

- Wildlife funding.

- Funding and support for the Salton Sea.

- Climate.

“Preserve California” Bills

Three of the bills we were supporting — Senate Bills (SB) 49, 50 and 51, collectively called the “Preserve California” package – will provide protection under California law if Trump’s administration weakens federal environmental laws and policies. SB 49 establishes baseline protection for water and air quality and endangered species so that California will continue to have environmental standards at least as strong as the federal laws that were in place on January 1, 2017.

SB 40 would give California the right of first refusal to purchase any federal land that the U.S. government tries to sell in the state.…

Bird Rescue staff JD Bergeron and Cheryl Reynolds bring one of three carrying cases with herons and egrets. / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Bird Rescue staff JD Bergeron and Cheryl Reynolds bring one of three carrying cases with herons and egrets. / Photo by Ilana DeBare Snowy Egrets ready for release / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Snowy Egrets ready for release / Photo by Ilana DeBare Heron rescue volunteers including Linda Vallee get the honor of releasing the birds / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Heron rescue volunteers including Linda Vallee get the honor of releasing the birds / Photo by Ilana DeBare Night-herons venture out of their carrying case. / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Night-herons venture out of their carrying case. / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Adult falcon flying from the Campanile on July 5. If you look closely, a juvenile is perched in the niche next to the righthand fleur de lis. Photo by Elizabeth Winstead.

Adult falcon flying from the Campanile on July 5. If you look closely, a juvenile is perched in the niche next to the righthand fleur de lis. Photo by Elizabeth Winstead. Adult falcon on Campanile. Photo by Elizabeth Winstead.

Adult falcon on Campanile. Photo by Elizabeth Winstead.

Young night-heron in tree slated for removal / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Young night-heron in tree slated for removal / Photo by Ilana DeBare

The nest on the trailer. Photo by Eric Schroeder

The nest on the trailer. Photo by Eric Schroeder Blackbird nest lining, including horse hair. Photo by Eric Schroeder

Blackbird nest lining, including horse hair. Photo by Eric Schroeder