First BioBlitz at Pier 94 finds 168 species

By Ilana DeBare

The Audubon Christmas Bird Count has been called the grandparent of all citizen science events. That might make a BioBlitz the newest grandchild – young, tech-savvy, and inviting all ages to play.

Like a CBC, a BioBlitz mobilizes regular citizens to document their nature sightings during a 24-hour period of time. But it includes not just birds but all kinds of living things, from grasses and lichens to insects, mammals, and mollusks. Participants don’t need to have any prior expertise, so it’s a great event for people new to nature or to the area, or for families with children. And it invites people to capture their sightings on their cellphones, so they can be easily ID’d with help from scientists and naturalists at the end of the blitz.

On April 1, 2017, we were delighted to co-sponsor the first BioBlitz at Pier 94, a Port of San Francisco property along the city’s San Francisco’s southeastern waterfront that we are working to restore as wildlife habitat.

SF Bay makes a stunning backdrop for counting shoreline species, Photo by Liam O’Brien

SF Bay makes a stunning backdrop for counting shoreline species, Photo by Liam O’Brien

American Avocets during the Pier 94 BioBlitz by Noreen Weeden

American Avocets during the Pier 94 BioBlitz by Noreen Weeden

Thirty-three participants of all ages fanned out across the five-acre site. They made 683 observations of 168 species, including 40 bird species.

The most common bird sightings were Red-winged Blackbirds and American Avocets in breeding plumage, showing how birds have made themselves at home in both the wetlands and uplands sections of the site. Large numbers of Clark’s and Western Grebes, American Wigeons, Mew Gulls, Western Gulls, California Gulls, and Canada Geese were also found.

All ages took part in the BioBlitz / Photo by Eleanor Briccetti

All ages took part in the BioBlitz / Photo by Eleanor Briccetti

Lincoln Sparrow during the Pier 94 BioBlitz by Liam O’Brien

Lincoln Sparrow during the Pier 94 BioBlitz by Liam O’Brien

Among the non-avian species were a harbor seal, common raccoon, black-tailed jackrabbit, Olympia oyster, and Western pygmy blue butterflies. Although the blitz took place in the morning, a few hardy souls returned that night to look for moths. Heavy winds meant that they missed all but one species of moth, the white-speck. But being there at night allowed them to hear the shorebirds chattering at dusk and to see one unidentified species of bat.

The Pier 94 BioBlitz was co-sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance, California Academy of Sciences, the Port of San Francisco, and the EcoCenter at Heron’s Head Park. Liam O’Brien, San Francisco’s resident butterfly expert, helped with the planning and the event itself.…

The large, iridescent blueback pipevine swallowtail butterfly lays eggs on Dutchman’s pipeline — the only host plant for the caterpillars of this native butterfly —in Glen Schneider’s Berkeley garden. Photo by Glen Schneider.

The large, iridescent blueback pipevine swallowtail butterfly lays eggs on Dutchman’s pipeline — the only host plant for the caterpillars of this native butterfly —in Glen Schneider’s Berkeley garden. Photo by Glen Schneider. Glen Schneider converted a former driveway to a berry and vegetable garden, providing food for his family. The local native plants have attracted forty-six species of birds, twelve species of butterflies, and more than two hundred types of insects and spiders. Photo by Kathy Kramer.

Glen Schneider converted a former driveway to a berry and vegetable garden, providing food for his family. The local native plants have attracted forty-six species of birds, twelve species of butterflies, and more than two hundred types of insects and spiders. Photo by Kathy Kramer. The blossoms of the checkerbloom attract painted lady butterflies and skippers to Merle Norman’s garden.…

The blossoms of the checkerbloom attract painted lady butterflies and skippers to Merle Norman’s garden.…

Young Black-crowned Night-Heron in care this month at Bird Rescue. Note the green and gold leg bandage. (Oakland A’s colors!) Photo by Isabel Luevano.

Young Black-crowned Night-Heron in care this month at Bird Rescue. Note the green and gold leg bandage. (Oakland A’s colors!) Photo by Isabel Luevano.

Young night-herons in care at Bird Rescue in 2015. Photo by Cheryl Reynolds.

Young night-herons in care at Bird Rescue in 2015. Photo by Cheryl Reynolds.

Chandler Robbins banding an albatross in 1966 / Photo by USFWS

Chandler Robbins banding an albatross in 1966 / Photo by USFWS

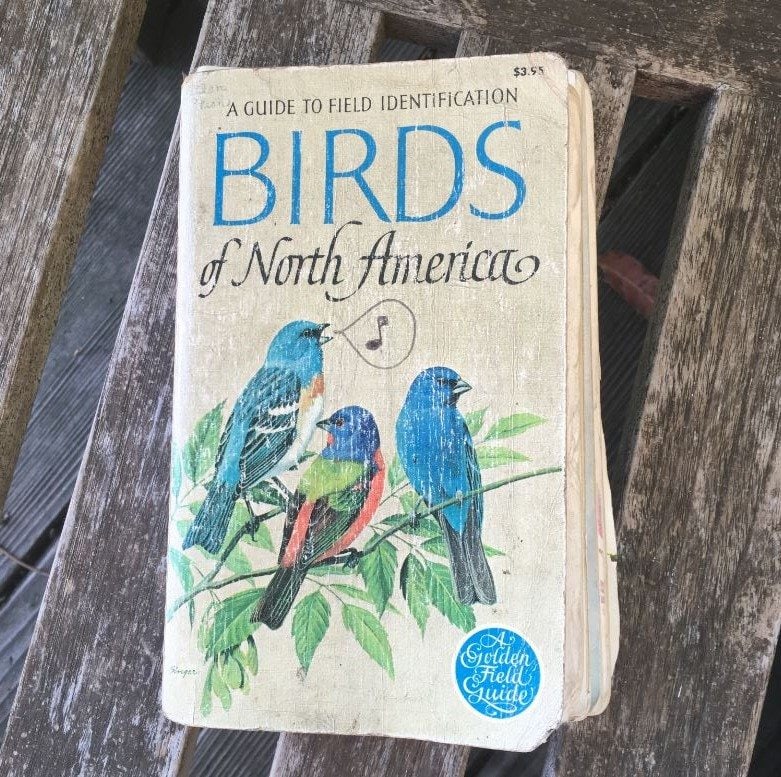

Allen Fish’s first field guide, with musical embellishment

Allen Fish’s first field guide, with musical embellishment

Common Yellowthroats in a plumeria by Rigel Stuhmiller

Common Yellowthroats in a plumeria by Rigel Stuhmiller

Indigo Buntings in dogwood by Rigel Stuhmiller

Indigo Buntings in dogwood by Rigel Stuhmiller