Monofilament recycling spreads to SF

In 2015, Golden Gate Bird Alliance started an initiative to save the lives of S.F. Bay water birds and marine mammals through the recycling of monofilament fishing line. Our volunteers built recycling containers out of PVC pipe, and we arranged for them to be placed at popular East Bay fishing spots. This week, the Port of San Francisco followed suit, thanks to the initiative of filmmaker Judy Irving. The following is a story that appeared on KTVU’s web site.

Receptacles for used recreational fishing line and hooks, which could cause the demise of pelicans, have been placed this week at nine popular fishing spots in San Francisco, port officials said today.

The receptacles were installed Monday and Tuesday at locations along San Francisco Bay, including Hyde Street Harbor, Fisherman’s Wharf, Pier 7, Pier 14, Rincon Park, Brannan Street Wharf Park, Aqua Vista Park, Bayview Gateway Park and Heron’s Head Park.

“Getting tangled up in fishhooks and fishing line are two of the most common problems that pelicans face in the wild,” documentary filmmaker Judy Irving said.

Pelican entangled in discarded fishing line

Pelican entangled in discarded fishing line

Irving produced and directed “Pelican Dreams,” a story about pelicans in the wild, as well as “The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill.”

The receptacles are made from 6-inch plumbing pipe, which was fastened to the pier at Pier 14. The pipe can be removed and the line and hooks collected for recycling.

“It will save pelicans’ lives,” Irving said.

A tenth receptacle will be installed at Pier30/32 and talks with federal officials are expected to begin soon about installing receptacles on federal lands around San Francisco such as in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, port officials said.

Installing recycling bins at MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline in 2015

Installing recycling bins at MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline in 2015

Port staff may install receptacles at other San Francisco locations too.

“We know that fishing line can really harm wildlife,” the port’s interim Executive Director Elaine Forbes said. She said the port takes environmental stewardship very seriously.

Irving said San Francisco officials acted quickly after she asked Supervisor Aaron Peskin whether anything could be done to stop the harm from fishing hooks and lines.

Peskin met with Forbes and struck the agreement. The receptacles cost $100 to make. The whole project cost $1,200, Forbes said.

“This is truly government at its best: responsive to residents’ ideas and pushing cost-effective solutions, all within a relatively short period of time,” Peskin said in a statement.…

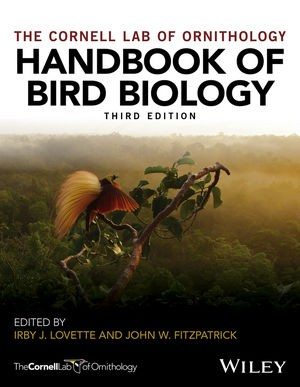

Third edition of the Handbook of Bird Biology

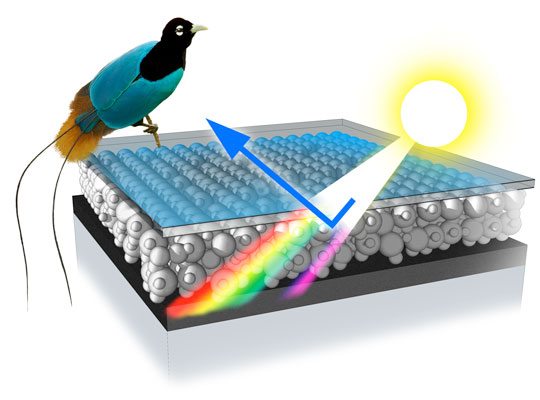

Third edition of the Handbook of Bird Biology Illustration of how blue feathers come from the structure of keratin proteins, rather than pigments. From the Handbook of Bird Biology by Andrew Leach.

Illustration of how blue feathers come from the structure of keratin proteins, rather than pigments. From the Handbook of Bird Biology by Andrew Leach. The Royal Flycatcher’s facial bristles help detect prey during aerial foraging, by Andrew Snyder.

The Royal Flycatcher’s facial bristles help detect prey during aerial foraging, by Andrew Snyder.

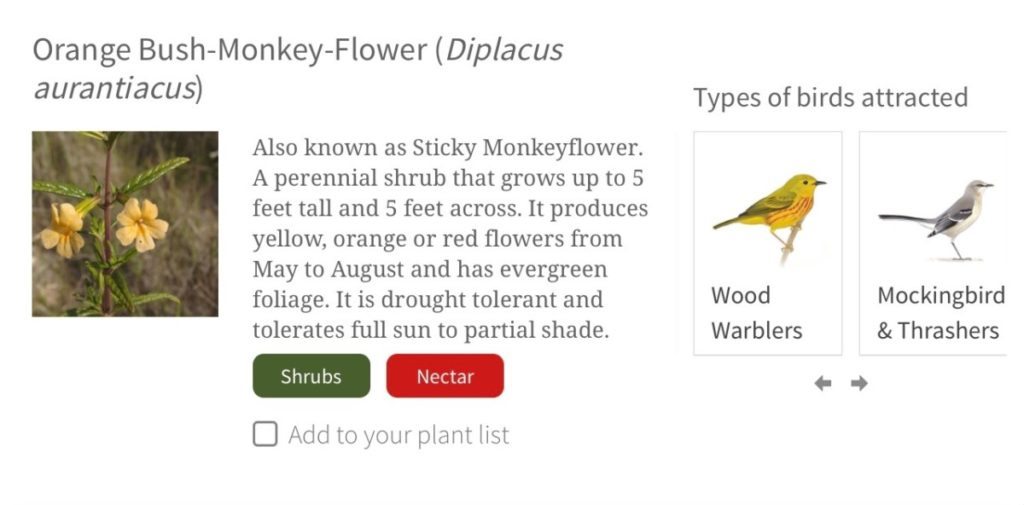

From NAS’s Plants for Birds web site

From NAS’s Plants for Birds web site Allen’s Hummingbird by Bob Gunderson

Allen’s Hummingbird by Bob Gunderson