Point Isabel: Birding Hotspot

By Jess Beebe

Most people think of Point Isabel primarily as a dog park, and indeed it features one of the largest and most scenic off-leash dog areas anywhere. But this park is also the gateway to a premier birding destination, offering access to a delightful stretch of the San Francisco Bay Trail that meanders through a restored salt marsh and slough and past expansive mudflats.

Tires, shopping carts, and chunks of concrete remind us that this place – like many shoreline parks – has a checkered history of human use. (It was acquired by the East Bay Regional Park District in 1975 to offset the construction of the neighboring Postal Service facility.) Here, as elsewhere, the Bay Trail runs parallel to a busy freeway. Yet the place has a wild beauty that transcends the heavy impact by people, both past and present, and makes it a worthwhile destination even for nature lovers who generally prefer more pristine places.

The mudflats and salt marsh provide outstanding habitat for shorebirds year-round and ducks in winter. Upland habitat hosts warblers and other songbirds. But without a doubt, the star resident is the Ridgway’s Rail. This species was known as the Clapper Rail until 2014, when the West Coast population was declared distinct from Gulf and Atlantic populations and given its own name. The interpretive displays along the Bay Trail still refer to the birds as Clapper Rails. Whatever you call this species, it is classified as endangered, both federally and in California, mainly due to habitat loss.

Tidal channel west of the Bay Trail near Point Isabel / Photo by Jess Beebe

Tidal channel west of the Bay Trail near Point Isabel / Photo by Jess Beebe

Ridgway’s Rail (formerly California Clapper Rail / Photo by Bob Lewis

Ridgway’s Rail (formerly California Clapper Rail / Photo by Bob Lewis

Rails are known for their secretive habits. They spend much of their time hidden deep in the salt marsh, venturing out onto the muddy banks of the channels only occasionally, and often for just moments at a time, before disappearing back into the marsh.

I saw my first Ridgway’s Rail on a trip to the Upper Coast of Texas. A fellow birder had told me that they could reliably be seen alongside a certain road on the Bolivar Peninsula. Determined to finally lay eyes on one of these elusive birds, I brought a sandwich and staked out the muddy marsh edge. About two hours later, a rail appeared. Having seen that rail – if only briefly – I felt more confident searching for them at Point Isabel, and later that season I spotted one there, too.…

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book

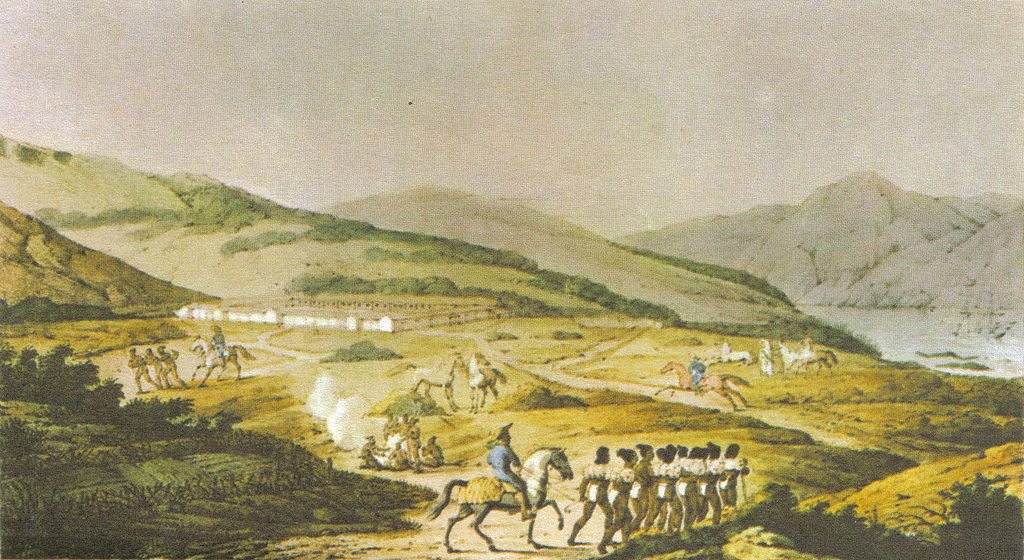

The Presidio in 1817 by Louis Choris

The Presidio in 1817 by Louis Choris Planes lined up at Crissy Field in the 1920s / Wikipedia

Planes lined up at Crissy Field in the 1920s / Wikipedia Crissy Lagoon today / Photo by David Assmann

Crissy Lagoon today / Photo by David Assmann

2016 Gwich’in Gathering in Arctic Village, Alaska / Photo by Susan Culliney

2016 Gwich’in Gathering in Arctic Village, Alaska / Photo by Susan Culliney Boats docked at Arctic Village, on the edge of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge / Photo by Susan Culliney

Boats docked at Arctic Village, on the edge of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge / Photo by Susan Culliney

Osprey pair with two chicks on June 8, 2016 by Richard Bangert

Osprey pair with two chicks on June 8, 2016 by Richard Bangert Two-month-old Osprey lands on fence that keeps people from approaching the nest site.

Two-month-old Osprey lands on fence that keeps people from approaching the nest site. Legs of the navigation light stand are rusted through. Light was erected in 1940.

Legs of the navigation light stand are rusted through. Light was erected in 1940.