The boldness of the Bewick’s Wren

By Eric Schroeder

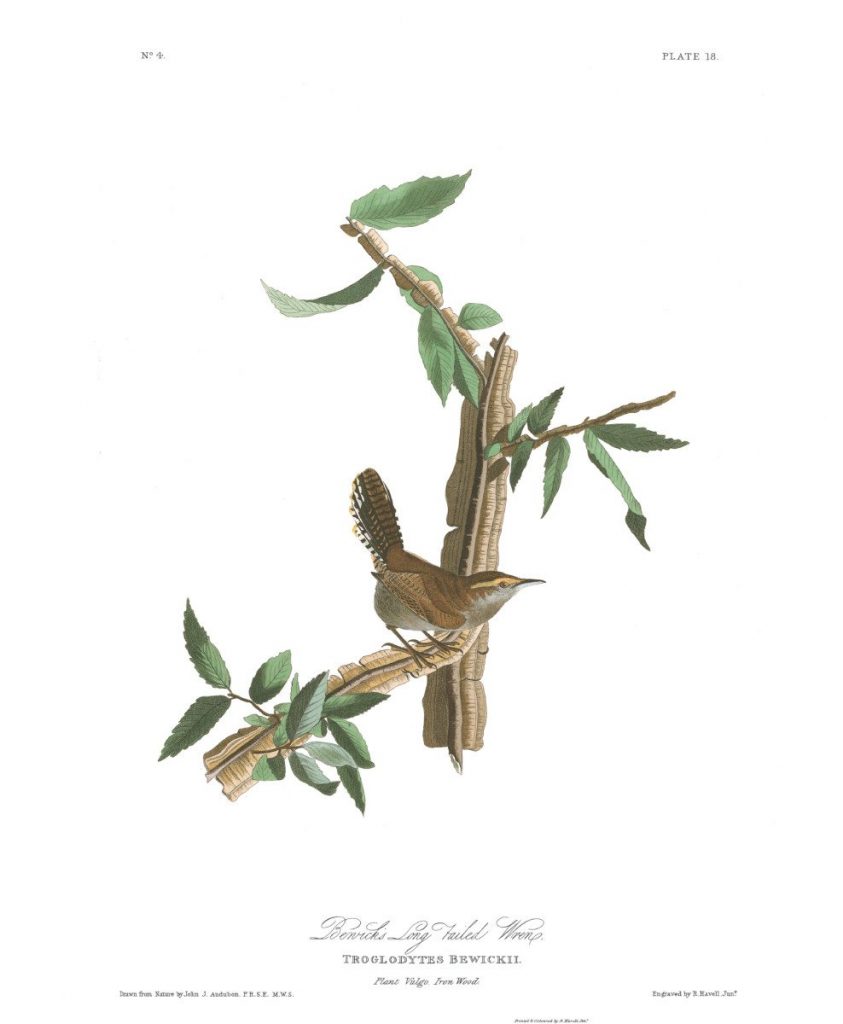

“Adorable” is how my wife Susan once described the Bewick’s Wren, and even non-birders would agree with the aptness of the description. These wrens are brown on their backs, wings, tails, and heads, and grey on their bellies. The bill is curved, the tail is long, and the outer tail feathers show white.

Most distinctive is the long, pronounced white eyebrow that helps to distinguish the Bewick’s from the House Wren that it most resembles in the west and southwest. This eyebrow gives it a cocky appearance—contributing to the “adorable” effect. Bewick’s are small, slender birds, averaging a bit over five inches in length and weighing only about a third of an ounce. But their size is belied by their bold character.

Their boldness is perhaps most evident in their song. For such a small bird, the Bewick’s Wren has tremendous vocal range and power. A male bird can have up to sixteen different songs. They can be tireless, too: In early spring, singing can take up to half of the male’s time. It’s no wonder that one of the names for a group of wrens is a “chime”—the others being a flock, a flight, and a herd! On a recent bird walk in the Oakland Hills, Golden Gate Bird Alliance birding instructor Bob Lewis said that when you hear a bird you can’t immediately identify by song, Bewick’s Wren is often the right guess. I’m becoming more familiar with my resident male’s repertoire, but he is still capable of fooling me on occasion.

Bewick’s Wren in the backyard by Eric Schroeder

Bewick’s Wren in the backyard by Eric Schroeder

Primarily a New World species (the only exception being the Eurasian Wren), the Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii, was first collected by John James Audubon in Louisiana in the winter of 1821. Audubon named it after the English naturalist Thomas Bewick, whom Audubon met during a visit to England in 1827. Bewick was by then 74 years old and famous for his book A History of British Birds, recognized as a forerunner of modern field guides.

Bewick’s Wren by John James Audubon, Plate 18 in his Birds of America

Bewick’s Wren by John James Audubon, Plate 18 in his Birds of America

The Bewick’s was formerly beloved as the “house wren” of the Appalachians and the Midwest, but the species today has almost disappeared east of the Mississippi. Ironically, competition from the actual, later-arriving House Wren has been partly responsible for its steep decline in the east and parts of its traditional range in the west.…

Female Wood Duck and ducklings at Niles Staging Area in Fremont / Photo by Roseanne Smith

Female Wood Duck and ducklings at Niles Staging Area in Fremont / Photo by Roseanne Smith Male Wood Duck at Stow Lake / Photo by Alan Hopkins

Male Wood Duck at Stow Lake / Photo by Alan Hopkins

Pilarcitos Reservoir in the Peninsula Watershed / Photo by Emma Leonard, Bay Nature

Pilarcitos Reservoir in the Peninsula Watershed / Photo by Emma Leonard, Bay Nature

Juvenile Snowy Egrets awaiting please / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Juvenile Snowy Egrets awaiting please / Photo by Ilana DeBare Snowy Egret ventures out of its carrier / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Snowy Egret ventures out of its carrier / Photo by Ilana DeBare Released Snowy Egret flies into the marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Released Snowy Egret flies into the marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare Released night-heron flies out into the marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Released night-heron flies out into the marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare GGBA leads a bird walk under one of the nest trees

GGBA leads a bird walk under one of the nest trees Adult night-heron in Oakland nest tree / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Adult night-heron in Oakland nest tree / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Black-capped Chickadee in Alaska with deformed bill / Photo by Martin Renner

Black-capped Chickadee in Alaska with deformed bill / Photo by Martin Renner

Red-breasted Nuthatch with elongated beak, by Diane Henderson (USGS)

Red-breasted Nuthatch with elongated beak, by Diane Henderson (USGS)