Alvaro Jaramillo on birding

Editor’s Note: Golden Gate Bird Alliance members may be familiar with Alvaro Jaramillo from the pelagic and international birding trips he leads through his business, Alvaro’s Adventures. But Alvaro, born in Chile, also writes the “Identify Yourself” feature for Bird Watcher’s Digest and authored the new American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of California. He will be featured in three events at the Monterey Bay Birding Festival in September. In preparation, Alvaro was interviewed by the festival’s Debbie Diersch. This interview is reprinted with permission from The Albatross, the newsletter of the Santa Cruz Bird Club.

Q: Alvaro, what do you want readers to know about you?

As far as birding goes, I’m different from some of the other people who are interested in bird ID and distribution because the main person I’m interested in reaching is the beginner or intermediate birder. It’s all about communicating this type of info to beginners/intermediate birders. I want them to know that it’s not all difficult or about trying to become skilled. When you put it in a way that makes it fun and simple, you don’t need to be a biologist to figure it out. I want to communicate to the every person.

As a young birder I was highly competitive. Let’s do a big day, keep a year list, but there came a time when it seemed empty. We have these wonderful birds, and it’s much richer than competition. Just enjoy the breeze, have a good dinner with friends, and make it the best it can be.

Alvaro Jaramillo on boat / Photo by Gail Stevens

Alvaro Jaramillo on boat / Photo by Gail Stevens

Q: What do you find most fascinating about birds and birding?

It’s the most versatile and unending kind of endeavor you can get into. You can do everything else while you bird. You can even play tennis and bird at the same time. It adds to almost anything else you can do. Birds take you to places that are amazing. We go out on the bay and see killer whales as well as birds. You might not have gotten there if you weren’t going for the birds in the first place. I can’t imagine any other pastime you can have that is more fluid, diverse, and rich, and that adds another element to of life in this way.

Q: Why did you decide to write the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of California and what makes it special?…

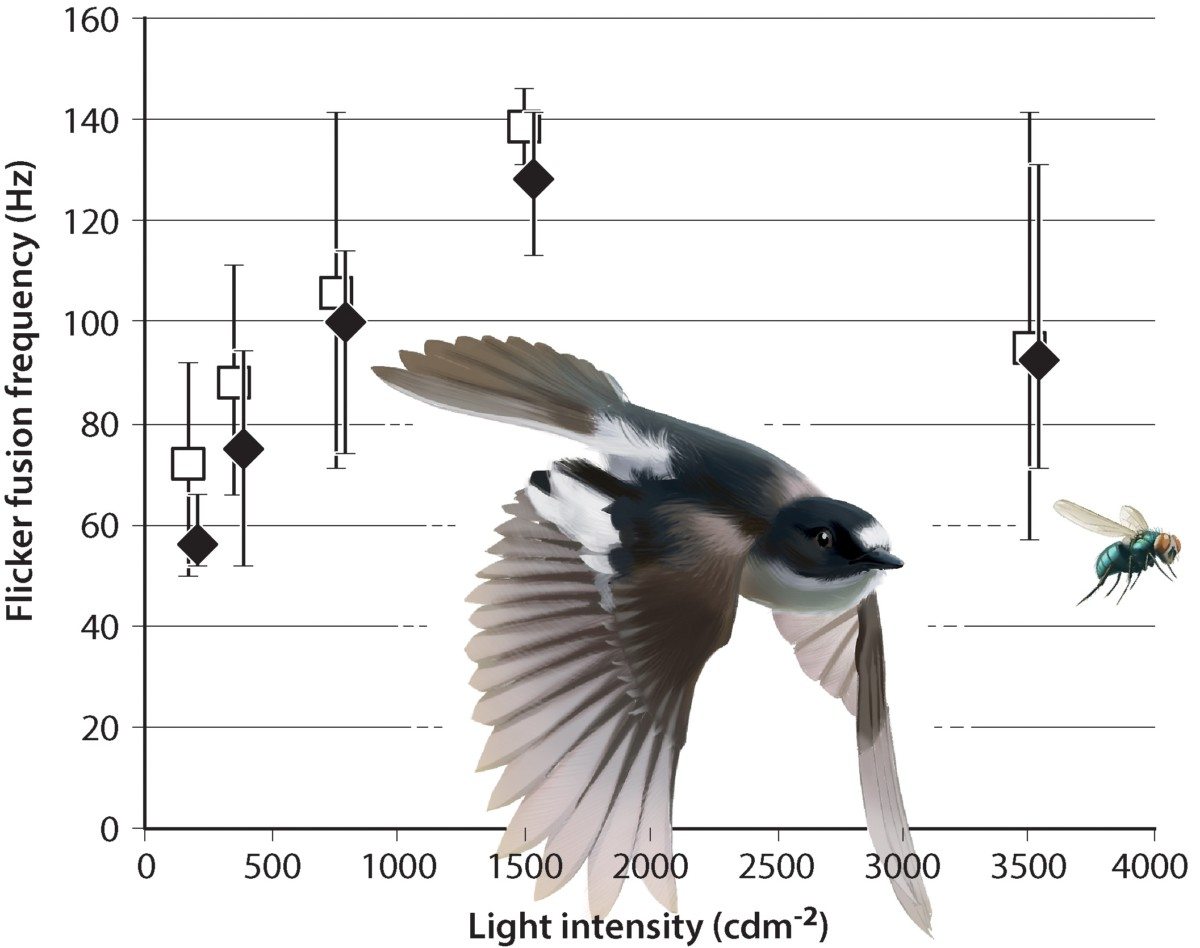

Flicker fusion frequencies for Collared (closed diamonds) and Pied Flycatchers (open squares). From PLoS One website. Averages are shown together with ranges for seven Collared and eight Pied Flycatchers tested repeatedly in different light intensities. Note that the speed of birds’ vision peaks in middle light intensities, when it is not too light and not too dark.

Flicker fusion frequencies for Collared (closed diamonds) and Pied Flycatchers (open squares). From PLoS One website. Averages are shown together with ranges for seven Collared and eight Pied Flycatchers tested repeatedly in different light intensities. Note that the speed of birds’ vision peaks in middle light intensities, when it is not too light and not too dark.

View of Mount Shasta by Harry Fuller

View of Mount Shasta by Harry Fuller

Lesser Prairie-Chicken by Tony Ilfland (USFWS)

Lesser Prairie-Chicken by Tony Ilfland (USFWS)

Marissa Ortega-Welch of GGBA and the Korematsu students. Photo by Sharon Beals

Marissa Ortega-Welch of GGBA and the Korematsu students. Photo by Sharon Beals