Imprisoned bird artist, now free as a bird

By Leslie Lakes

Nearly eleven years ago, a friend told me about a special art auction that was being held by the Fortune Society in New York. What made this auction unique was that all the works were by incarcerated individuals – men and women serving sentences in prisons throughout the United States. The artwork could be seen either on an online auction site, or at a live exhibition on the Upper East Side in Manhattan. Approximately 250 pieces of original artwork in various media and sizes were available for sale via a bidding process for a period of five days.

I was living in New Jersey at the time and, as an artist myself, was intrigued. As I found out, the Fortune Society began in 1967 when David Rothenberg produced a play — Fortune in Men’s Eyes, about the harsh realities of living in prison – that mesmerized the audience and generated public discussion. Rothenberg went on to found the Fortune Society to support successful reentry of prisoners into society and alternatives to incarceration.

I perused the artwork in the auction and was amazed at the depth of sensitivity, skill, creativity, and ingenuity. The artists often relied on such minimal “art supplies” as hand-made paintbrushes fashioned from human hair, pigments made from dyes in M&M and Skittle candies, “oil paints” made from mixing peanut butter with candy dyes, and “washes” made from coffee and tea.

American Goldfinch by Keith Harward

American Goldfinch by Keith Harward

I was so blown away that I asked the Fortune Society to provide me with the names and contact information of some of the incarcerated artists. That is what started, back in January 2006, my longtime and regular correspondence with artist Keith Harward. To date, I have over 250 letters from Keith, along with a slew of small (approximately 5×7 inch) charming drawings of… birds.

Birds galore. Birds of all kinds. What can I say? Keith loves birds!

Calliope Hummingbird by Keith Harward

Calliope Hummingbird by Keith Harward

Baltimore Oriole by Keith Harward

Baltimore Oriole by Keith Harward

Tufted Titmouse by Keith Harward

Tufted Titmouse by Keith Harward

Keith developed his connection to birds as a child in Greensboro, North Carolina, from backyard feeders and field guides. But before his incarceration, he’d never been an artist. As he phrases it, the only things he’d painted were “cars, houses and ‘the town.’ ”

Then in 1982, as a 27-year-old U.S. Navy sailor, he was charged with murdering a man and raping his wife. The killer was in fact another sailor on Keith’s ship.…

Harlequin Ducks at Wilson Creek, by Patricia Bacchetti

Harlequin Ducks at Wilson Creek, by Patricia Bacchetti

Common Murre by Patricia Bacchetti

Common Murre by Patricia Bacchetti

Rhinoceros Auklet by Patricia Bacchetti

Rhinoceros Auklet by Patricia Bacchetti

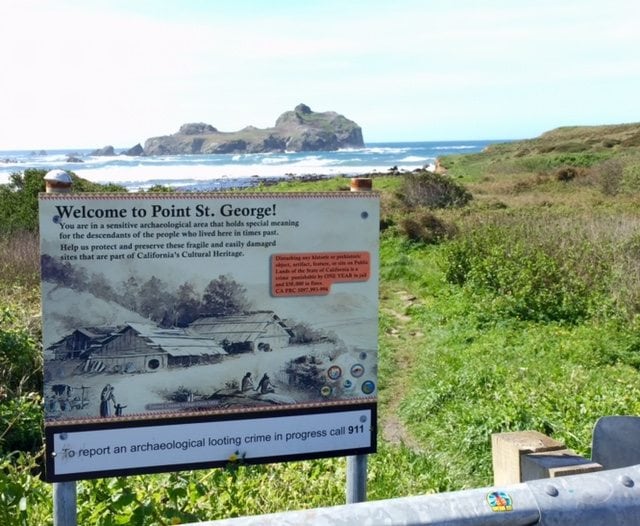

Castle Rock at Point St George / Photo by Patricia Bacchetti

Castle Rock at Point St George / Photo by Patricia Bacchetti

Off-leash dog at Ocean Beach / Photo by Jouko van der Kruijssen

Off-leash dog at Ocean Beach / Photo by Jouko van der Kruijssen

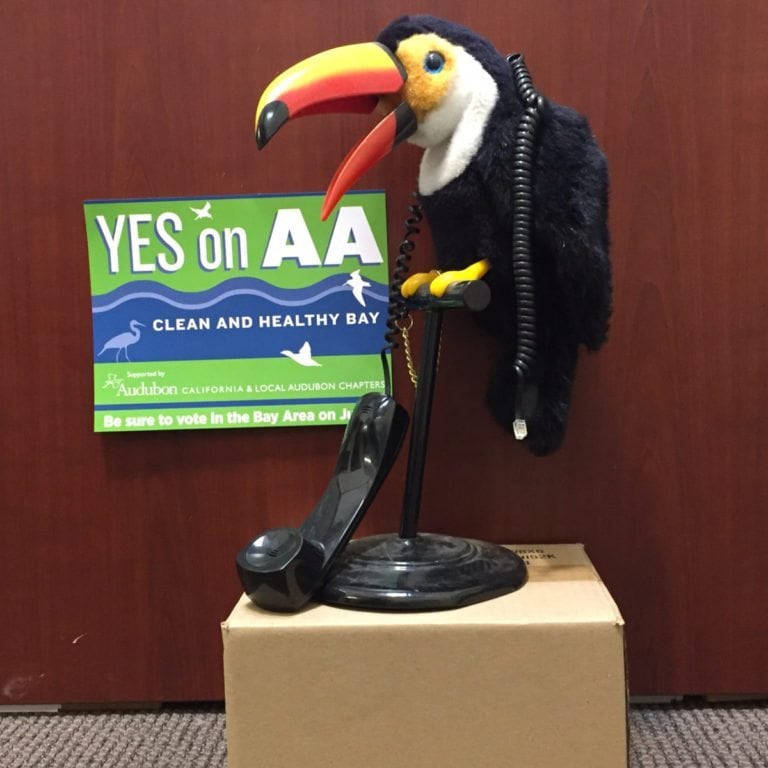

The birds can’t phone bank for Measure AA, but we can!

The birds can’t phone bank for Measure AA, but we can!

Bob Power and his Southern Alameda County team.

Bob Power and his Southern Alameda County team.

Board President Alan Harper presents Glen Tepke with his second place award for the Big Six Hours category.

Board President Alan Harper presents Glen Tepke with his second place award for the Big Six Hours category.

Laughing Gull on Hayward Shoreline Birdathon trip, by Chris Wills

Laughing Gull on Hayward Shoreline Birdathon trip, by Chris Wills

Bob Lewis with the Best Bird award for Laughing Gull at Hayward Shoreline.

Bob Lewis with the Best Bird award for Laughing Gull at Hayward Shoreline.

Lobos Creek dunes / Photo by Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

Lobos Creek dunes / Photo by Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

Bewick’s Wren by Bob Lewis

Bewick’s Wren by Bob Lewis