Record number of Snowy Plovers on Ocean Beach

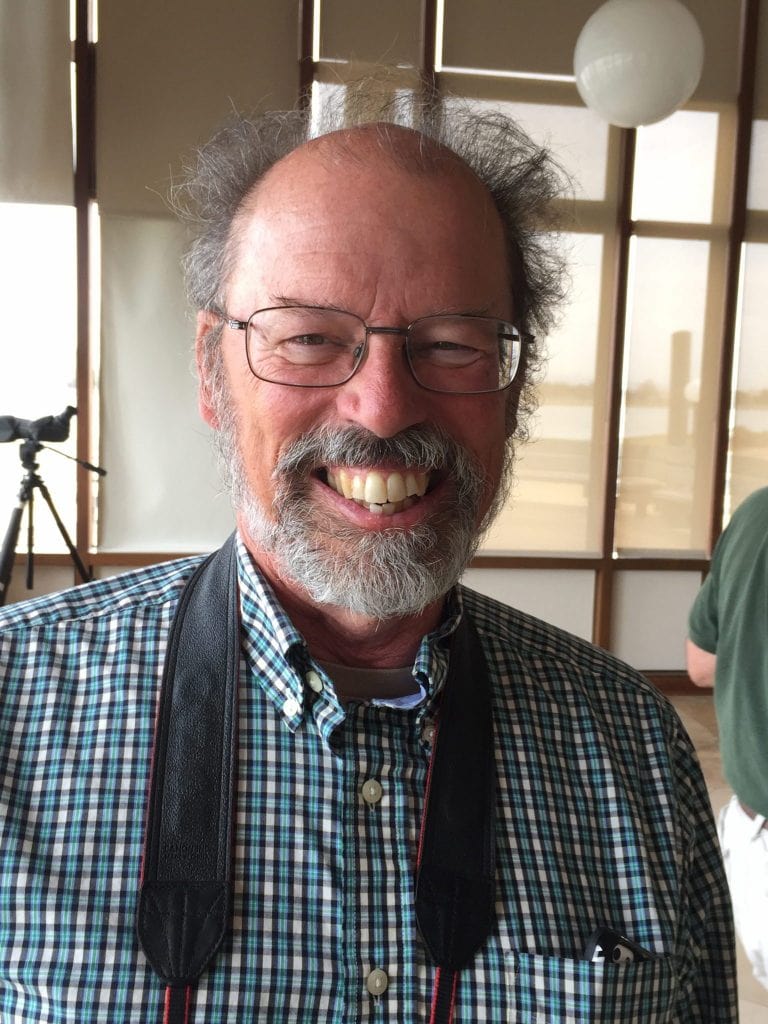

Editor’s Note: The San Francisco Chronicle ran an excellent story this weekend on San Francisco’s Snowy Plovers, which we are reprinting here in case you missed it. Our only quibble is with their description of longtime GGBA stalwart Dan Murphy as a… “hobby birder!” That’s kind of like describing Stephen Curry as an “adequate basketball player.” (Wink.) Click here to view the original story with the Chronicle’s plover photos.

By Lizzie Johnson

Tucked among the dunes of Ocean Beach, dozens of white-breasted shorebirds roost. And this year, their numbers have quadrupled.

The sandy shores of the Crissy Field Wildlife Protection Area and Ocean Beach are a stopping-point for the Western snowy plover, a 6-inch shorebird with dark patches on its back. The average count at the bird’s overwintering ground is usually in the mid-20s. But this January, National Park Service workers counted as many as 104 plovers in a single day.

That’s a record number since the Park Service began observing and monitoring the population in 1994, a year after the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the species as threatened. The snowy plover population on the West Coast — with 85 percent in California, and some in Oregon and Washington — has dwindled to 2,100 individuals, and they remain threatened by habitat loss, predation and human population growth.

Adult male Western Snowy Plover / Photo by Jerry Ting

Adult male Western Snowy Plover / Photo by Jerry Ting

Local number grows

“It’s really exciting that we have so many of these birds out there at the western edge of San Francisco,” said Bill Merkle, wildlife ecologist for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. “The last couple of years, the local population has been increasing, especially this year. It is likely because the birds had good breeding years.”

But local numbers aren’t indicative of an overall snowy plover growth trend. The population has remained steady, largely because of habitat protection and education, said Andrea Jones, director of bird conservation for Audubon California.

“The population hasn’t been increasing or decreasing as a general trend,” Jones said. “That is both good and bad. There is a ton that goes into protecting these birds in their nesting habitats. At the same time, the population isn’t getting to where it needs to be.”

It has been tough for the species to recover because the snowy plover breeds and overwinters in different places, said Cindy Margulis, executive director of the Golden Gate Bird Alliance. The birds breed in coastal dune habitats in areas like Monterey and the Point Reyes National Seashore, and then rest in San Francisco during July through April.…

Debris at Chabot Gun Club / Photo by gritphilm (Creative Commons)

Debris at Chabot Gun Club / Photo by gritphilm (Creative Commons) Male Bald Eagle at Lake Chabot / Photo by Mary Malec

Male Bald Eagle at Lake Chabot / Photo by Mary Malec

Black Phoebe landing on a rock by Bob Lewis

Black Phoebe landing on a rock by Bob Lewis Common Loon feeding young in British Columbia, by Bob Lewis

Common Loon feeding young in British Columbia, by Bob Lewis Bob (left) leads a class field trip to Coyote Hills in 2013, by Ilana DeBare

Bob (left) leads a class field trip to Coyote Hills in 2013, by Ilana DeBare

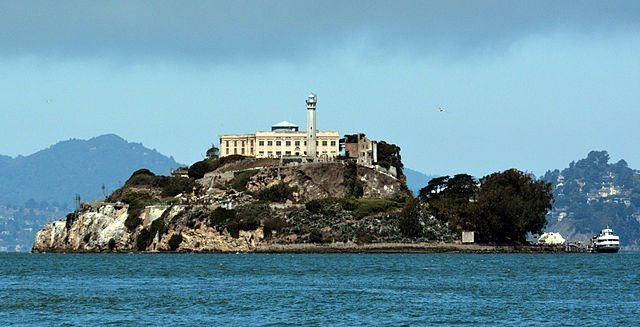

An almost National Geographic moment with Snowy Egrets on Alcatraz, by Bonnie Brown

An almost National Geographic moment with Snowy Egrets on Alcatraz, by Bonnie Brown

Fashionable docent attire!

Fashionable docent attire!