Birds of Northern California — new field guide

By Bob Lewis

This small field guide, published by R.W. Morse Co. of Olympia, Washington, slides easily into a back pocket. Small in size, but somehow able to cram 502 pages full of details on over 400 Northern California bird species, this photographic guide bucks the “bigger is better” trend of many popular guides.

The authors of Birds of Northern California are well known to many Bay Area birders. Dave Quady, the principal author, is known as the Grey Owl to many of us: Famous for teaching owling classes and leading field trips for Golden Gate Bird Alliance, Dave is President of Western Field Ornithologists. Jon Dunn’s name appears as principal author of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, and many of us have traveled with Jon to far-away places as he guides Wings field trips. His publication list is long, and his knowledge of local and world birds legendary. Kimball Garrett, as Ornithology Collections manager of the Natural History Museum of L.A. County, brings extensive knowledge of the status and distribution of California’s birds, and Brian Small’s photographs have appeared regularly on the covers of every bird publication there is. He’s co-author of three other photographic field guides.

Birds of Northern California

Birds of Northern California

This is a photographic guide. The pages are small, and often only a single species appears on a page. This contrasts to larger guides using artwork, where several species can be compared on a single page. Graphic Designer Christina Merwin has, however, done a good job of placing similar species on the same page where possible. Examples are Hooded and Bullock’s Orioles; Bell’s and Sagebrush Sparrows; Dusky and Gray Flycatchers; Peregrine and Prairie Falcon.

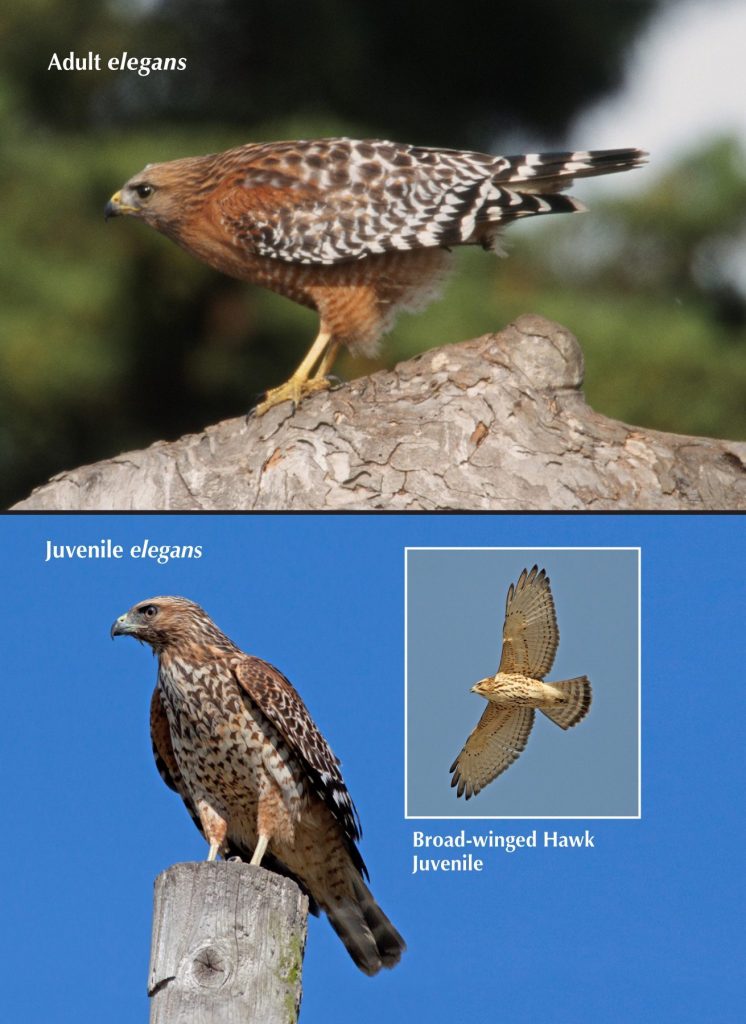

Red-shouldered Hawk photo page from Birds of Northern California

Red-shouldered Hawk photo page from Birds of Northern California

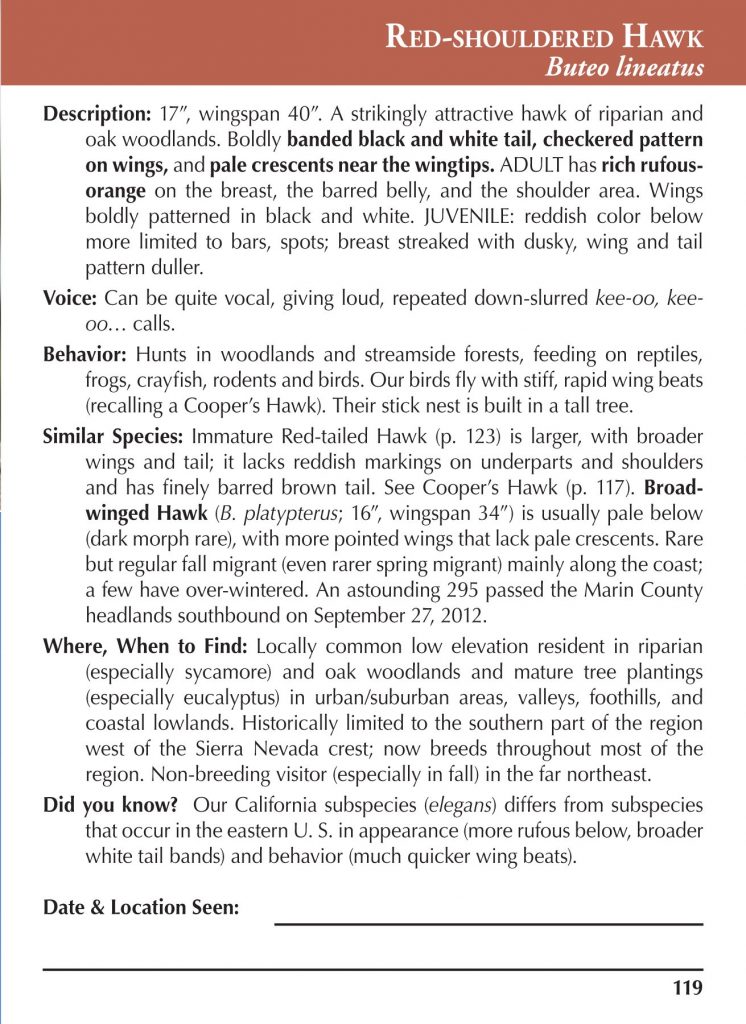

Red-shouldered Hawk text page, next to the photo page

Red-shouldered Hawk text page, next to the photo page

The photographs are sharp and generally posed in a slight angle toward the reader, ideal for showing off as many field marks as possible. Many species are illustrated in several plumages: male and female, basic and alternate. immature and adult. 468 of the 650 bird images are by Brian Small; some of the remainder are by Northern California photographers known to readers of The Gull, including Jerry Ting and Glen Tepke. (Editor’s note: Bob Lewis has a photo in the guide too!) There are two maps by our own Rusty Scalf, showing public lands and habitats in Northern California.

Habitat map by Rusty Scalf in Birds of Northern California

Habitat map by Rusty Scalf in Birds of Northern California

The book is organized taxonomically, covering the most common species found in the area.…