Master Birder class opens eyes, enhances skills

By Ilana DeBare

Most of the beachgoers hurried obliviously through the parking lot, intent on reaching the sand and the waves. But for one group of about 20 people, the parking lot was the main attraction.

There in the Monterey pine! Those little dark shapes that looked like pine cones! Through a scope, they were in fact Cedar Waxwings. And just a little further on, the willows were filled with Yellow-rumped Warblers, Townsend’s Warblers, Ruby-crowned Kinglets….

This was the next-to-last field trip of the year for the Master Birder class co-sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance and California Academy of Sciences – a mid-November trip to Stinson Beach, Bolinas Lagoon, and the amazing studio of bird artist Keith Hansen.

For the twenty Master Birder participants, the advanced year-long class involved much more than being able to spot warblers and waxwings. Over the course of 2014, they:

- Chose a local birding “patch,” visited it at least twice a month, and kept a field notebook of their findings.

- Examined and handled dozens of bird specimens from the Academy’s collections.

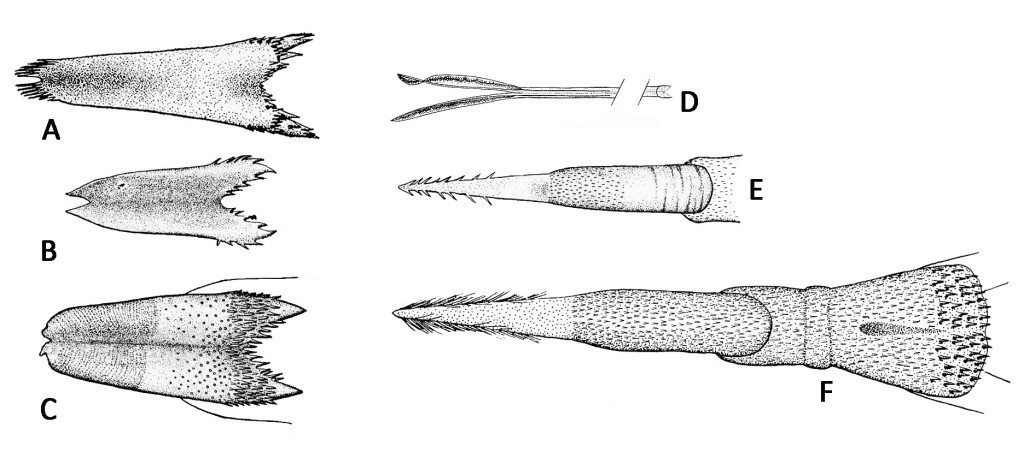

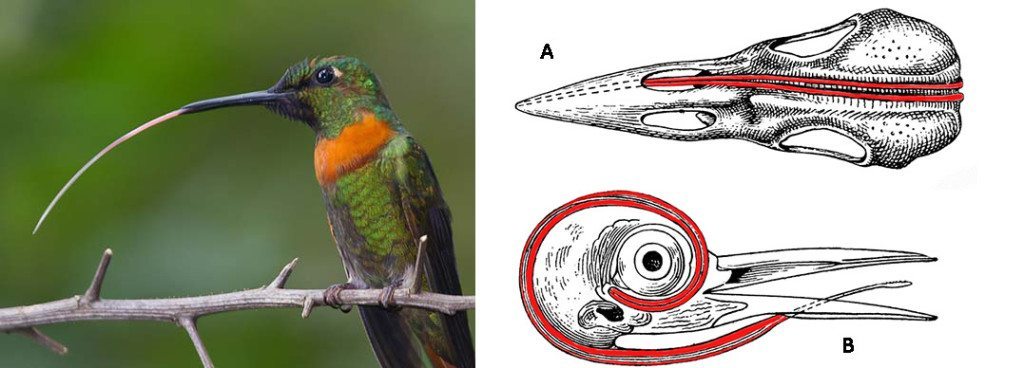

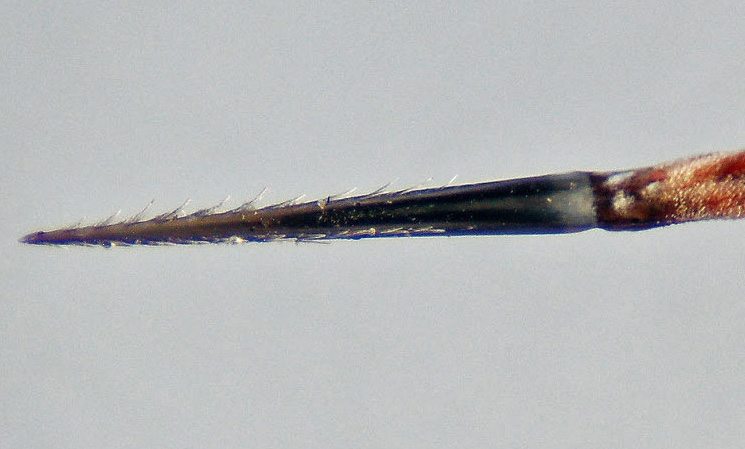

- Learned about bird anatomy, evolution, behavior, and calls, as well as habitats and plants associated with different birds.

- Wrote descriptions and personal observation of three different bird species.

- Delivered a ten-minute talk on an aspect of birds or ornithology.

- Took part in over 20 field trips

- Led a field trip themselves – often for the first time!

- Volunteered over 100 hours for a conservation organization.

It sounds daunting. But participants said the class was one of the high points of their lives as birders.

Master Birders at Bolinas Lagoon / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Master Birders at Bolinas Lagoon / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Yellow-rumped Warbler / Photo by Bob Lewis

Yellow-rumped Warbler / Photo by Bob Lewis

“I’ve taken a lot of Audubon classes, and in this one, the content is really broad and detailed,” said Rachel Davidson. “Having it spread out over the course of a year solidifies your understanding.”

“The lectures were amazing,” said Jane Hart. “Bob talked about what produces color on birds, Eddie talked about changes in the Bay Area landscape since early geological time, and Jack talked about migration. It just makes you want to learn.”

Hart was referring to the class’s three co-instructors – GGBA board member Bob Lewis, naturalist Eddie Bartley, and Cal Academy curator of birds and mammals Jack Dumbacher.

2014 was the second year that the three of them had taught the class. (NOTE: They will be teaching it again this year, starting in February.…