Sutro Forest – conservation gem or lost opportunity?

People who live outside of San Francisco are often unaware of the existence of this small open space preserve in the middle of San Francisco.

Mount Sutro is the northernmost forested peak of the San Francisco Central Highlands that continue south through Twin Peaks and Mount Davidson, all with summits in the 900-foot range. The south-east saddle between Mount Sutro and Twin Peaks sports the big red and white TV tower that is sometimes the only thing visible above the summer fog. The north slope of Mount Sutro is home to the Parnassus Campus of the UCSF Medical School–and 61 acres surrounding the summit contains Mount Sutro Open Space Preserve. Together with the contiguous San Francisco Interior Greenbelt, this parcel represents the largest remaining fragment of a massive forest planted beginning in 1886 by Adolf Sutro.

Today, blue gum eucalyptus trees of differing ages cover most of the preserve, along with scattered cypress and pine trees. Fog caught by the canopy drips into the forest, and in places sword ferns and moss line the trails, which remain muddy long after the last rain.

In several places, the middle canopy contains Blackwood Acacia and Red Elderberry. Some areas also contain flowering plums that produce ethereal blooms in the spring as the branches reach for light. Most of the understory is dense Himalayan Blackberry and Cape and English ivy that has climbed many of the trees.

The southern slope was heavily thinned in 1935 and the summit was clearcut in the 1950s to accommodate a NIKE radar site. The summit has now been restored to a native plant meadow created using volunteer labor and a grant from the Rotary Club. Sometimes walking on the adjacent Twin Peaks can be harsh, windy and cold, while walking on Mt. Sutro is sheltered and peaceful.

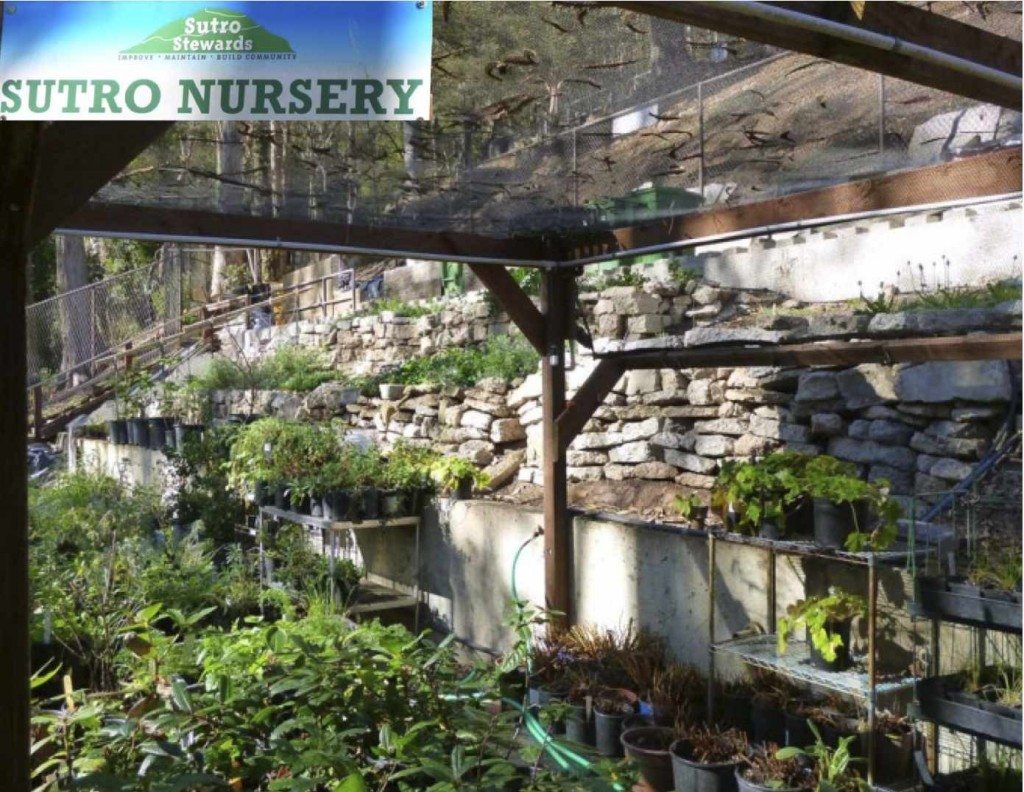

The forest has always had a few well-traveled trails, but recently a network of well-graded trails has been built or improved by the volunteer hard labor of the Sutro Stewards and community volunteers under the direction of Craig Dawson. One of the exciting surprises of trail building was that when a few trees were felled and the Himalayan Blackberry and Ivy were cleared for construction, beautiful, long-dormant native plants sprang to life along the trails in several places. In the last couple of years, the Stewards and their volunteers have put major work into developing a native plant nursery which now provides plants for maintaining the summit meadow and for diversifying trail-side plant communities wherever possible.

The forest fills the view out of my south windows, and I have walked through it since I moved here in 1976. I picked Sutro Forest last year as “my patch” for a Master Birder Class assignment. During 2013, I submitted 47 Mount Sutro eBird checklists reporting about 53 species (four additional checklists submitted during 2013 by other birders added a few more species). Pacific Wrens’ exuberant, extended song filled the forest from February ‘til late July, and they often perched just at eye level.

The other dominant bird of the aural landscape was, of course, the Song Sparrow. Wilson’s Warblers were like little balls of glowing bright golden-yellow as they hover-gleaned in the shady, often foggy, forest in the mid- and understory. I saw the Wilson’s fuzzy grey fledglings, and the slightly older adolescents who weren’t quite proficient yet at feeding on the wing. Swainson’s Thrush and Olive-sided Flycatcher each sang in Woodland Canyon for several weeks during the summer. Common Ravens are also a constant presence in the sky above, making sport around the TV tower and the tops of the trees, and sometimes lurking in the lower levels. During migration, the number of species on Mount Sutro swells.

I love hiking the Sutro Forest trails with my binoculars (See this map for access points.) But most San Francisco birders prefer nearby Mount Davidson Park. During 2013, three times as many eBird checklists were submitted for Mount Davidson Park, with over twice the number of species reported. More intense birding of Mount Davidson by more diverse and expert birders accounts for some of the difference, but habitat diversity may be the most important factor. Like Mount Sutro, Mount Davidson hosts a small fragment of the original Sutro Forest, but unlike Mount Sutro, the eastern third of the park was never planted with eucalyptus, and it remains coastal scrub/coastal prairie.

Over the years many factors — including too-densely-spaced trees, insect pests, and climbing ivy — have degraded the health of Mount Sutro Forest. In early 2013, it looked like UCSF was poised to begin a series of visionary management projects in the preserve. The aims included reduction of fire hazard, improvement of the health of the forest, and, importantly from a conservation point of view, diversification of habitat. The first long-range plan was published in 2001, and an updated version was finally presented in early 2013 in a Draft Environmental Impact Report.

The forest was to be thinned in four small plots totaling 7.5 acres, with the understory treated in different ways. A half-acre plot would provide a view corridor of the city. My favorite plot would be an attempt to restore Woodland Creek as a year-round riparian corridor. This restoration would entail removing water-hungry eucalyptus and opening up the canopy for conversion planting to native trees and shrubs. The outcomes in these initial small areas would guide future management of larger areas of the forest over several years. All that was needed for work to begin was acceptance of the EIR.

At a February 2013 community meeting presenting the draft EIR, 80 percent of the comments were from well-organized, unified opposition to any tree removal. The remaining 20 percent of the comments mostly advocated some form of management, but they were not unified behind a single goal. Most of the individuals who had participated in development of the management plan over 18 years remained silent since the plan contained their vision and the recommendations of consulting experts, and had been arrived at through broad consensus.

The management plan called for limited herbicide use in one small demonstration area, but the draft EIR was required to describe the impact if use was widely expanded. Opposition to herbicide use was close to 100 percent.

In the face of these comments, UCSF was silent for many months. Routine maintenance and fire mitigation that didn’t require an EIR were carried out. Then in November 2013, UCSF suddenly announced that the draft EIR had been withdrawn. All the years of planning — all of the years of community participation, the multiple hours of research and development of the draft EIR — all were aborted in favor of a new plan that scuttles everything but fire hazard reduction.

The reason cited by UCSF at a recent meeting was that community consensus was limited to forest safety and opposition to herbicide use. The revised plan describes cutting all trees less than 10 inches in diameter in 25 acres of forest, without regard to health or species. Yet in one particularly unhealthy area, there may be no live trees over 10 inches in diameter. The plan does not include any provision for regeneration of an understory with value to wildlife. It describes only biannual “mowing” of the understory, with the chipped materials to be spread on the site. This means there will be no habitat for birds and other wildlife in nearly half of the forest.

As of now, the November 2013 plan has been placed on hold by the University. They cite limited manpower to write the DEIR right now, but pressure from the UCSF Community Advisory Group and the wider community is certainly also a factor. The question now is whether UCSF can be convinced to reconsider the November plan and to return to the conservation vision that was part of earlier plans. If not, it looks like we will be moving towards the destruction of an urban oasis rather than the creation of a conservation gem on Mount Sutro.

What You Can Do

The big lesson here is that people who want to see positive changes in Sutro Forest should make their voices heard. Bad decisions in this case were made, in part, because conservation-minded people were not vocal or unified enough at the critical time.

Take a walk in Sutro Forest, check out the birds, and evaluate the health and diversity of the habitat for yourself. Pay particular attention to areas such as the Rotary Garden, the Interior Greenbelt, and the upper Historic Trail to see the fruits of previous attempts to diversify habitat and protect native species. Check out the Sutro Stewards website for excellent guided walks April 13 and 26 (donation suggested) and a Nursery Open house (free) on April 27.

If you get a chance, glance through the previous EIR and the November 2013 presentation. There may be another opportunity to weigh in officially in the future. In the meantime, please encourage UCSF to reject plans that eliminate conservation opportunities and to return to their previous plans that contained visionary opportunities for habitat diversification. You can send emails to Vice Chancellor Barbara French at bfrench@ucsf.edu and Associate Vice Chancellor for Campus Planning Lori Yamauchi at LYamauchi@planning.ucsf.edu; please cc us at ggas@goldengatebirdalliance.org.

———————————-

Patricia Greene has lived in San Francisco since 1972 and been birding for the past 17 years. She’s taken many Golden Gate Bird Alliance classes, including the inaugural Master Birder class in 2013, which inspired her to keep notes on her birding observations and to join GGBA’ San Francisco Conservation Committee. Together with Jeffrey Black, she leads Bike and Bird field trips for GGBA and Grizzly Peak Cyclists.