The Cost of our Choices: Calculating Your Carbon Footprint

By Bruce Mast

I checked my carbon footprint last night. Why, you might ask? Well, it was either that or step on the bathroom scale. Both have about the same effect—vaguely unpleasant but much-needed reminders about how my choices impact either my health or the planet’s health. The science around my personal choices still seems murky—count calories or just carbs? More exercise? More protein? Good cholesterol? My head spins. But despite what a few naysayers would have us think, the basic science underpinning climate change is straightforward. When we burn fossil fuels for energy, we add more and more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This buildup acts like a blanket that traps heat around the world, which disrupts the climate. Heat buildup drives ever more frequent and extreme weather events. The hots get hotter, the colds get colder, the wets get wetter, the drys get drier, and storms pack a more powerful punch.

Of course, climate change affects humans in numerous (mostly negative) ways, but birding has further attuned me to how it stresses my feathered friends. If it wasn’t already hard enough being a bird in the face of habitat loss, outdoor cats, light pollution, and on and on, now birds must cope with the increasing prevalence of extreme heat waves, drought, wildfires, and shifting seasons that disrupt essential food sources. I derive great joy from birds and nature, and I want my nieces, nephews, and their children to enjoy the same experiences. So it’s painful to watch bird numbers decline year after year, knowing that my carbon emissions contribute to the problem.

Compared to my personal health, my choices influencing my carbon footprint are more complicated because I reject the notion that I should make heroic sacrifices to save the planet. The problem is simply too big for a handful of altruists to solve on their own. The solution requires all of us and . Only when planet-saving choices align well with individual self-interests can we expect people to adopt those choices on a mass scale.

On the other hand, I can’t just point my finger at “those other people” who need to change their ways—Big oil! China! Big Coal!—again, the solution requires all of us. I can get on my soapbox about how “the government” should take action to bring climate-friendly choices within reach, but when our elected leaders take action to do so, then it’s up to us (and me!) to say yes.

So periodically, I take a look at my carbon footprint to remind myself where I should focus my attention. A carbon footprint is a simple estimation of how much heat-trapping carbon dioxide and related greenhouse gases my activities produce in a year. The numbers are inexact because I don’t want to spend the effort to rigorously measure all the inputs required for a true quantitative estimate. But that’s okay because what’s important in this context is the relative contribution from different choices. I don’t want to waste any mental energy worrying about tiny changes that don’t improve my carbon “bottom line.” I’m a big fan of the household calculator from UC Berkeley’s Cool Climate Network, but there are other legitimate calculators as well.

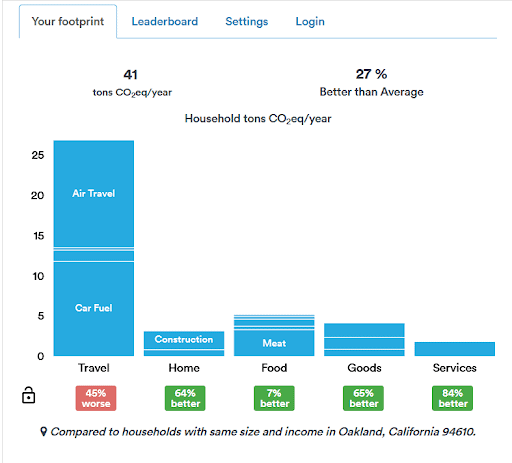

We’re a middle-aged, two-adult household in a 1920s-vintage Oakland bungalow. Here’s what our household footprint looks like.

You can see we do pretty well by most measures. We’re not avid consumers of goods and services, and we’ve made substantial home improvements to eliminate fossil gas appliances (heat pumps and induction stoves rock!), improve energy efficiency, and add rooftop solar. Our home improvement choices have been a financial stretch, but they have improved our home’s comfort and indoor air quality while shielding us from PG&E rate increases—that is, our planet-saving choices have also aligned well with our self-interests. We don’t eat much processed food, but we could do better in the food category if we were willing to give up meat. In this case, our planet-saving choices conflict with our self-interests, based on our understanding of our nutritional needs. (Yes, I’ve learned to live with the moral tension of being a meat-eating climate champion.)

And then there is travel, both car fuel and air travel. This category represents the moral tension I experience in spades. We could heroically swear off air travel, but it would mean not visiting aging parents and overseas friends. The overseas travel for birding trips is arguably more discretionary, but I have seen firsthand in multiple places how our ecotourism dollars are the only force holding the loggers at bay. While eliminating air travel would slash our carbon footprint, our lives would be greatly impoverished as a result. In lieu of personal sacrifices, we need societal solutions such as low-carbon jet fuels and fast and convenient rail transportation. These solutions require big policy and systems changes that dwarf my personal choices.

Car fuel for ground travel, on the other hand, is increasingly my personal responsibility. Back in the day, my wife bought a plug-in hybrid car, which momentarily made us climate heroes by powering our around-town miles with clean electricity. But it still burns gas, and I still roll around the state on birding adventures in a gas-guzzling Jeep. Meanwhile, both state and federal leaders have been proactive about bringing electric vehicles within reach—supporting research and development, bringing manufacturing onshore, offering tax credits and incentives, raising fuel efficiency standards, investing in charging infrastructure. EVs are coming out in more models, with longer ranges and more affordable price points. It’s now up to me to get rid of my gas-guzzling Jeep and go electric.

It’s not yet an easy step. Good electric alternatives to Jeep Wranglers are still a year or two away, unless I’m willing to sell a kidney to buy a Rivian. But my Jeep has 170,000 miles on it, and it’s getting expensive to keep it running. My self-interest tells me that the time to retire the Jeep and get an EV is right around the corner. When I do, my emissions from local travel will mostly get erased, and my overall carbon footprint will go way down. I knew that intuitively, but a periodic peek at my carbon footprint helps me keep my eye on the ball. I hope you’ll join me in reviewing your own carbon footprint and pursuing prudent choices to protect both our short-term and long-term interests, our treasured birds, and our friends and loved ones.

Bruce Mast is a nationally recognized thought leader on residential green building. He helped found the nonprofit Build It Green in 2004 and has served as its Deputy Executive Director since 2006, leading business development activities and translating Build It Green’s strategic priorities into practical program designs. He honed his birding and citizen science skills as a volunteer at Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge in Central Texas, where he mapped nesting territories of endangered Black-capped Vireos and Golden-cheeked Warblers. He also served as a City Council member for City of Albany, California, and a high school science teacher in the Peace Corps in Benin, West Africa. Bruce holds a BA in Physics from Rice University.