The Revive & Restore project to de-extinct birds

By Jack Dumbacher

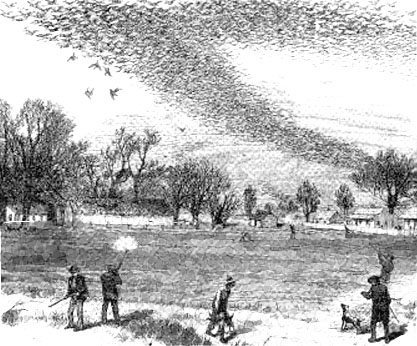

What iconic north American bird used to be the most abundant bird species on earth, but is definitely not on your life list? The Passenger Pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius. But if Bay Area innovators Stewart Brand and Ryan Phelan have their way, you may be able to see them again, live in feathered form.

Extinction – the end of a gene pool – is regarded as the final step from which there is no return. It is as final as final can be. Extinction is something to be feared and respected, and many conservation workers spend their lives trying to prevent their favorite species from slipping into this oblivion. But is it really final?

There is a growing team of people — led by Brand, whom you may remember as publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog from the 1960s through the ’90s — who are asking whether de-extinction is possible. They have gathered geneticists, ethicists, behaviorists, evolutionary biologists, all to turn their tools and creativity to de-extinct a single species.

The species they have chosen as their flagship goal is the Passenger Pigeon.

Apart from being the quintessential American extinction, it has a few things going for it. Just a couple years ago, genetic data suggested that its closest living relative is the Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata), and not the Mourning Dove as many had thought [1]. This suggests that the Band-tailed Pigeon may be able to act as a surrogate parent and sort of genome template.

New technology is available that is allowing Beth Shapiro at U.C. Santa Cruz and colleagues to sequence the whole genome of the Passenger Pigeon from snippets of century-old museum skins. Geneticists like George Church at Harvard Medical School are developing techniques for taking a closely related genome (i.e. the Band-tailed Pigeon) and performing “site-directed mutagenesis” to carefully alter the key genes that differ between the two, and make them more like the Passenger Pigeon. Using these technologies they don’t have to create the entire Passenger Pigeon genome from scratch; they can modify the Band-tailed genome so that it becomes effectively a Passenger Pigeon.

Once the genome is reconstructed, they will need other folks who can transfer it into the nucleus of a living cell, and then transfer that nucleus into an egg. Then incubate the egg, hatch the chick, feed it, and teach it to fly. The last steps might even be done by Band-tailed Pigeon adults.

Every one of these steps requires the most advanced scientific techniques, and many skills and tools not yet invented. There are ethical questions that boggle the mind. But at a meeting last week in Washington, D.C., a large and growing group of people focused their attention on this problem. Many think that the question is not whether this is possible but how soon can we realize the goal.

Although we are a long way away from realizing Jurassic Park, we might see “Early America Park” in our lifetimes. And if folks like Brand and Phelan are successful, you might get a few new lifers for your North American list….

What do you think? Is this an exciting way to possibly reverse some tragic species losses? A distraction from the serious environmental threats faced by other species today? We would love to hear your comments.

[1] Johnson, K.P., D.H. Clayton, J.P. Dumbacher, and R.C. Fleischer, The flight of the Passenger Pigeon: Phylogenetics and biogeographic history of an extinct species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2010. 57: p. 455-458.

————————————

Jack Dumbacher is a GGBA board member and Chair of the Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy at California Academy of Sciences. He has written for Golden Gate Birder on topics including the rivalry between Barred and Spotted Owls, how birds use a magnetic sense in migration and why birds in foggy coastal areas have smaller bills.