The Vanishing Chorus: A Reflection on North American Birds in Decline

by Kenneth Hillan

In the bustling and growing town of Paisley, Scotland—the place of my birth—a young Alexander Wilson once wandered the woodlands, unaware that his journey would lead him across the ocean to North America. From his letters home, what he encountered in the New World was beyond anything he had known or imagined: skies teeming with birds, forests alive with song, rivers echoing with nature’s pulse. Two centuries later, I reflect on Wilson’s experience—and the troubling question: what remains of that magnificent abundance today?

On May 1, 2025, a landmark study, published in Science, revealed a sobering truth1. Of 495 North American breeding bird species, fully three-quarters have declined significantly in some part of their range over the past 15 years. The research, led by Alison Johnston and a team at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is based on an analysis of nearly 37 million eBird checklists submitted by observers between 2007-2021. The conclusions from the research, grounded in rigorous data analysis combined with national as well as local habitats, paint a portrait of a continent in quiet crisis. A summary of key findings and takeaways from their publication can be found in a one page summary here.

Curiously, the decline is not always where one might expect. Some species appear to thrive in fragmented habitats—perhaps a mall here, a restored marsh there—offering the illusion of recovery. But these modest gains, while welcome, are dwarfed by losses in the vast habitats where these birds are most common, as populations are declining most severely where they are abundant.

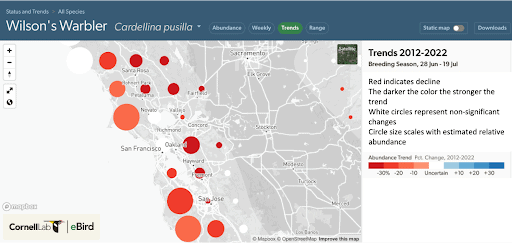

What sets this study apart is its use of fine-scale trend mapping—measuring bird population change in grids of approximately 10 square miles, rather than just looking across broad regions. This higher resolution has revealed a more nuanced picture: while most species are declining, many also show areas of local increase. For conservation groups like GGBA, this represents a powerful shift. It allows us not only to target urgent declines but also to identify and build upon local successes—guiding action where it can be most effective.

In the San Francisco Bay Area and the Central Valley, the study data highlights significant declines in wetland and coastal breeding birds, mirrored by parallel losses in the wintering populations of local species that breed in the North American Arctic.

Here in California, birds that depend on wetlands for breeding have been among the hardest hit. I looked back at my own eBird records for the Tricolored Blackbird—our near-endemic “California blackbird.” Between 2016 and today, I recorded sightings on six checklists, totaling 220 birds. That feels like a respectable number.

But wait, less than a century ago, Tricolored Blackbird colonies numbered in the tens or even hundreds of thousands. In the 1930s, a single colony was estimated to contain over 200,000 nests—roughly 300,000 adults—and covered nearly sixty acres. We need to reset our baseline of what a thriving population truly looks like.

The counties of the Bay Area still offer a remarkable diversity and abundance of birdlife. But let’s not be naïve. While we continue to enjoy and be amazed by every living thing around us, we are also bearing witness to what future generations may remember as an era of mass extinction.

This spring, I’ve been savoring the return of our breeding birds. One in particular stands out—Wilson’s Warbler, one of our most familiar summer warblers. Its accelerating trill is joyful and easy to recognize, and its bright yellow plumage and black cap are unmistakable. A song of spring—familiar and seemingly abundant.

But the data tell a different story. Based on eBird Trends data2, Wilson’s Warbler is in decline in the San Francisco Bay Area: in just 15 years, its population is down 18% in Marin, 25% in San Francisco, and 33% in the East Bay counties. It’s shocking—but who would have known without the data?

Back in 2023, while documenting breeding birds for the Marin County Breeding Bird Atlas 2, I recall the thrill of confirming breeding by two species in one moment: a tiny Wilson’s Warbler parent doing its damnedest to feed a hungry Brown-headed Cowbird chick that was twice its size.

But was it always like this? Back in Alexander Wilson’s day, the Brown-headed Cowbird was known as the Buffalo Bird, named for its habit of following the enormous bison herds. At that time, its range was limited to the open grasslands of central North America. But as the bison disappeared and those grasslands were converted to farmland, the Brown-headed Cowbird spread westward, first recorded in California’s Sacramento Valley in the 1930s. Its relatively new presence in California may be a factor–yet one more–in the decline of Wilson’s Warblers.

Perhaps the most dangerous illusion is the belief that what we see today is what has always been. Each generation inherits a quieter world and assumes it is normal. Scientists call this the shifting baseline syndrome. I call it a kind of absentmindedness, and, in our unintentional blindness, we risk losing not only the birds themselves, but our capacity to imagine a richer world.

Coming from a different era and baseline, I wonder what stories Alexander Wilson could teach us—about the richness he witnessed, and the quiet we are learning to bear. These birds are not statistics. They are the spirit of a place—voices that have accompanied our ancestors, and may yet sing for our descendants, if we act.

Birders—patient, passionate, perceptive—are keepers of memory. You have seen the change. You have recorded it. And now, we can help to reverse it. The data tell a story not only of decline, but of potential. With stewardship, with care, and with attention to every part of the world around us, the recovery of our birds is possible.

So let us keep watching—each checklist, each walk, each note recorded and shared. Let us understand where and why these changes are happening around us—and use those insights to sharpen our conservation efforts on the ground. Let us speak up, and teach others to hear the music we remember. And above all, let us choose a future where the wild voices of the land do not fall silent—but rise once more in song.

Kenneth Hillan, originally from Scotland, graduated in medicine from the University of Glasgow before making the Bay Area his home. A fervent advocate for our winged companions, he is passionate about working with others to create a world where birds and humans can flourish together. Kenneth is a graduate of the 2022 Golden Gate Bird Alliance & California Academy of Sciences master birding class and is currently a block leader for the Marin County Breeding Bird Atlas 2 project.

Citations:

1) Johnston, Alison, et al. “North American Bird Declines Are Greatest Where Species Are Most Abundant.” Science, vol. 380, no. 6650, 2025, pp. 532–537. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adn43812) Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, S. Ligocki, O. Robinson, W. Hochachka, L. Jaromczyk, C. Crowley, K. Dunham, A. Stillman, C. Davis, M. Stokowski, P. Sharma, V. Pantoja, D. Burgin, P. Crowe, M. Bell, S. Ray, I. Davies, V. Ruiz-Gutierrez, C. Wood, A. Rodewald. 2024. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2023; Released: 2025. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://doi.org/10.2173/WZTW8903