Why birds in the coastal fog have smaller bills

By Jack Dumbacher

Some bird species show tremendous geographic variation in plumage or body measurements. For example, Fox Sparrows have a sooty Pacific form and a reddish Taiga form, Song Sparrows look different on the California coast than they do further north in the Pacific Northwest, and Dark-eyed Juncos – well, where does one begin…?

But most birders rarely consider that these subtle differences might be adaptations to local conditions. And it’s rarer still when there is scientific research suggesting how these differences evolve or make birds locally more fit.

Russ Greenberg, from the Smithsonian Institution’s Migratory Bird Center, has been studying differences in plumage and bill size in Song Sparrows and Swamp Sparrows for many years. He has long understood that different populations of sparrows have significant variation in bill size and shape, but figuring out the evolutionary function of the variation has been difficult.

Greenberg’s research group recently made a huge breakthrough by examining how birds lose heat. As we all know, birds’ bodies have a thick layer of feathers that provides superior insulation for heat and cold, so birds don’t lose much heat from their bodies. However, birds’ exposed bills and legs can dissipate a great deal of heat.

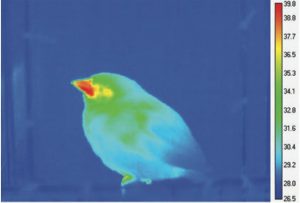

Using stunning infrared photography, Greenberg and his colleagues showed that bird bills can work as an effective “radiator” that burns off excess metabolic heat [1]. And because radiating heat does not waste water from evaporation (as does panting or sweating), it is an especially effective means for dissipating heat in dry environments, such as our California deserts. Meanwhile, in cooler environments, a smaller bill may prevent heat loss, thus helping to keep the birds warmer.

So with this potential explanation, Greenberg’s team needed birds to study. They turned to California Song Sparrows that are widespread and variable and live in a variety of habitats from the cooler coastal areas to the warm central valley, the Sierras and western deserts [2]. They measured almost 1,500 Song Sparrow bills from museum collections, including those at California Academy of Sciences and U.C. Berkeley.

They found an elegant correlation between bill size and average monthly high temperatures in the hottest month of the year. Bird populations on the cool coast have smaller bills to prevent heat loss; those in the warmer regions have larger bills to dissipate heat and keep birds cool.

The results suggest that there is a basic amount of heat that sparrows lose through their body, and so the primary means of adapting to new temperatures involves changing their bill size.

Move over, Darwin’s Finches – bill size isn’t just about what you eat.

————————–

[1] Greenberg, R., V. Cadena, R.M. Danner, and G. Tattersall, “Heat Loss May Explain Bill Size Differences between Birds Occupying Different Habitats.” PLoS ONE, 2012. 7(7): p. e40933.

[2] Greenberg, R. and R.M. Danner, “The Influences of the California Marine Layer on Bill Size in a Generalist Songbird.” Evolution, 2012.

—————————

Jack Dumbacher, a board member of Golden Gate Bird Alliance, is Chair of the Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy at California Academy of Sciences.