The boldness of the Bewick’s Wren

By Eric Schroeder

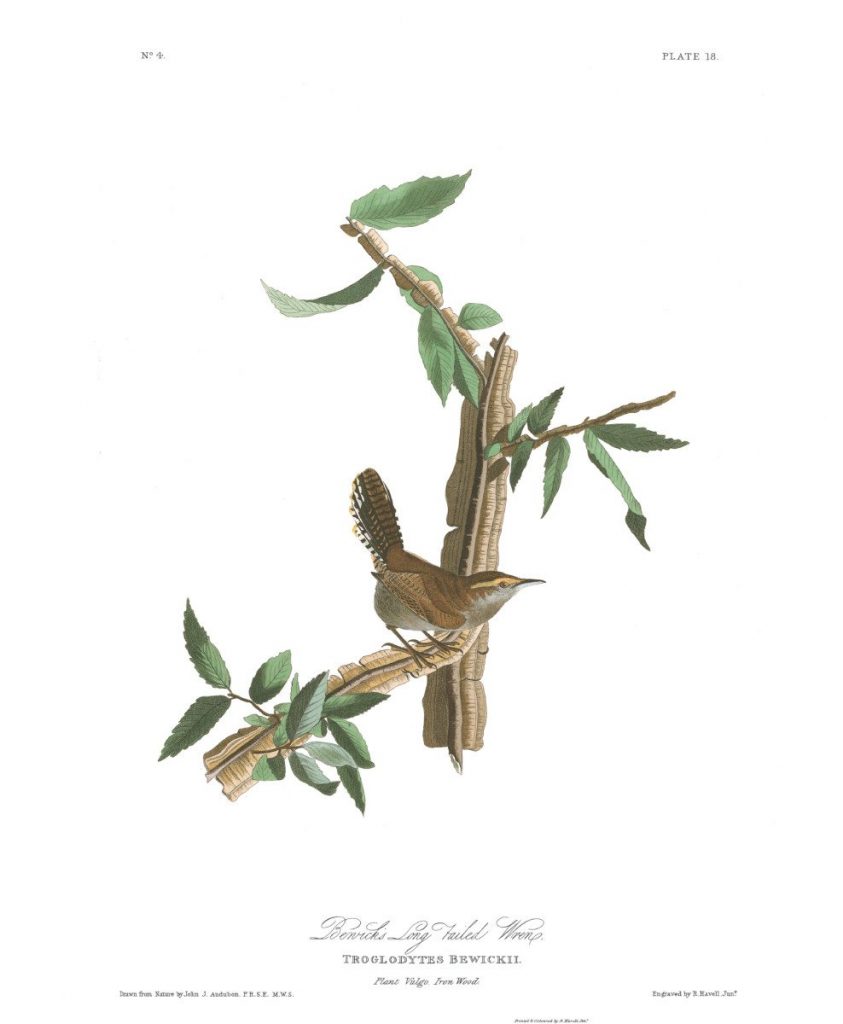

“Adorable” is how my wife Susan once described the Bewick’s Wren, and even non-birders would agree with the aptness of the description. These wrens are brown on their backs, wings, tails, and heads, and grey on their bellies. The bill is curved, the tail is long, and the outer tail feathers show white.

Most distinctive is the long, pronounced white eyebrow that helps to distinguish the Bewick’s from the House Wren that it most resembles in the west and southwest. This eyebrow gives it a cocky appearance—contributing to the “adorable” effect. Bewick’s are small, slender birds, averaging a bit over five inches in length and weighing only about a third of an ounce. But their size is belied by their bold character.

Their boldness is perhaps most evident in their song. For such a small bird, the Bewick’s Wren has tremendous vocal range and power. A male bird can have up to sixteen different songs. They can be tireless, too: In early spring, singing can take up to half of the male’s time. It’s no wonder that one of the names for a group of wrens is a “chime”—the others being a flock, a flight, and a herd! On a recent bird walk in the Oakland Hills, Golden Gate Bird Alliance birding instructor Bob Lewis said that when you hear a bird you can’t immediately identify by song, Bewick’s Wren is often the right guess. I’m becoming more familiar with my resident male’s repertoire, but he is still capable of fooling me on occasion.

Primarily a New World species (the only exception being the Eurasian Wren), the Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii, was first collected by John James Audubon in Louisiana in the winter of 1821. Audubon named it after the English naturalist Thomas Bewick, whom Audubon met during a visit to England in 1827. Bewick was by then 74 years old and famous for his book A History of British Birds, recognized as a forerunner of modern field guides.

The Bewick’s was formerly beloved as the “house wren” of the Appalachians and the Midwest, but the species today has almost disappeared east of the Mississippi. Ironically, competition from the actual, later-arriving House Wren has been partly responsible for its steep decline in the east and parts of its traditional range in the west. Researchers have reported that House Wrens are known to destroy the nests of Bewick’s, and they have also observed House Wrens attacking Bewick’s Wrens. The Bewick’s also faces competition from European Starlings, House Sparrows, Song Sparrows, and Carolina Wrens, though no friction has been observed between Bewick’s and Pacific Wrens. (It’s interesting that House Wrens and Carolina Wrens can co-exist, but both come into conflict with the Bewick’s.)

It’s surprising that a bird with such a bold character is seeing its territory decline through competition with other birds, though perhaps not surprising that some of those birds are other species of wrens. This bold character is attested by its Old High German alternate name, kuningilin or “kinglet,“ a name reflected in the fable of the “King of Birds.” The birds had a contest to see who could fly the highest: The winner would be king of birds. The eagle outflew all the other birds but was beaten by a small bird (a wren?) that had hidden in his plumage. This forward character is reflected in the wren’s inquisitive nature—the Bewick’s is quick to check out what’s new in its surroundings.

I noticed this trait earlier in the year when I put up an old birdhouse on the side of our garden shed and within minutes the Bewick’s was there, giving it a good look. The Bewick’s was constantly moving about to get different vantage points of the birdhouse, engaging in its characteristic tail wagging and cocking its brow at the vacant house.

This was the same birdhouse that a pair of Bewick’s had used as a nesting site several years earlier, settling right in. The wrens’ family name is Troglodytidae, which comes from the word “troglodyte” or cave-dweller: Not only do some wren species forage in dark crevices, but they are also cavity breeders. Bewick’s wrens build nests in various sorts of places—from rock crevices to abandoned cars—so the birdhouse must have seemed like a dream house.

The bird back then brought his mate to check out the new address and build a nest together. Generally the female Bewick’s starts laying eggs one to three days after the nest is complete and lays one egg a day until she has a clutch of five to six. The eggs are oval-shaped and white in color, with spots ranging from reddish brown to lilac. Two weeks later the chicks begin to hatch.

When our chicks hatched, the female remained inside the birdhouse on the nest while the male brought food for her. Females usually flee the nest if humans approach, but some have been known to remain even when prodded with a stick. Both the male and the female feed the chicks, which aren’t able to leave the nest for at least twelve days.. When they first leave the nest, young Bewick’s can fly well enough to avoid ground predators. They stay in the area with their parents until about two weeks after they have fledged, when they move off on their own.

When our local pair of Bewick’s was on their nest, my wife noticed juvenile birds also in our yard. She remembered hearing that Bewick’s Wrens were cooperative breeders—that young birds come back to the nest to help raise a new brood. I tried to find mention of this in my reading about the Bewick’s but couldn’t. In fact, I found out that the opposite phenomenon has been known to happen: Fledglings don’t leave the area and continue to beg food from their parents, causing nestlings to starve to death. Not so adorable.

Wrens are insectivores and their diet consists mainly of gleaned insects. Noted U.C. Berkeley researcher Edwin Miller spent a lot of time in the 1930s and 40s observing Bewick’s Wrens in Strawberry Canyon near the Berkeley campus. He documented their preference for thick brush, concluding that this was a foraging choice rather than a shelter choice. He also noted that in early spring when food was less plentiful, bonded males and females would sometimes forage together, with the female working close to the ground and the male higher up. The male would sometimes stop and feed the female.

Studying birds in the thick brush of Strawberry Canyon, Miller concluded that wrens don’t like to live around people. From what I’ve observed, Miller was wrong about this. When the Bewick’s male made his appearance in my yard this spring., he announced himself immediately. Soon he was looking over the old birdhouse in its new location. After a cursory inspection, he headed off to the dense leaf cover of the weeping pussy willow tree, seeing if it might be more suitable. But he didn’t seem bothered by my presence.

Just choosy about his new house.

Eric Schroeder is a retired U.C. Davis lecturer and administrator who still leads month-long Summer Abroad student program for UCD in South Africa and Australia. He enjoys viewing wildlife in the sky, on land, and under the sea. He’s currently enrolled in the year-long Master Birding class jointly sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance and the California Academy of Sciences.