Vaux’s Swifts in San Rafael, 2014

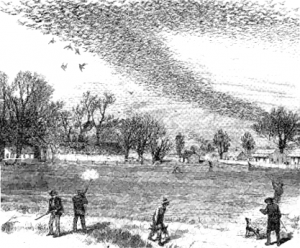

I absolutely love the energy associated with massive numbers of birds ingathering — especially at dusk. So I was treated to a particularly breathtaking marvel on September 19 as migrating Vaux Swifts swirled in the sky above the historic smokestacks at McNear’s Brick & Block in San Rafael.

As these astonishingly fast and acrobatic flyers awaited their moment to enter the roost, the sky was graced with a massive spiraling ribbon of birds. Breathtaking!

Adding to my own enthusiasm that evening was the fact that our own Rusty Scalf was there leading the counting of the swifts and attempting to detect – via radio telemetry – any of the six Vaux outfitted in Washington State with transmitters for their arduous autumnal migration down the Pacific Coast.

Rusty had discovered this Vaux roost for the birding community in 2010, when it occurred to him that the site’s dynamics matched those of other major collective migratory roost sites along the Pacific Flyway. This year Rusty marshaled several of GGBA’s dedicated volunteers — including participants in our Master Birder class — to help with the count.

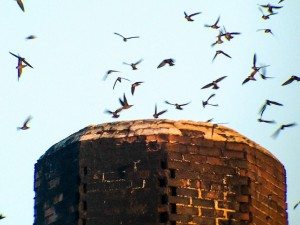

Faux’s Swifts approach the chimney in 2014 / Photo by Michael Helm

Faux’s Swifts approach the chimney in 2014 / Photo by Michael Helm

Vaux’s Swifts entering the chimney in 2014 / Photo by Michael Helm

Vaux’s Swifts entering the chimney in 2014 / Photo by Michael Helm

American Kestrel perched on the McNear chimney / Photo by Miya Lucas

American Kestrel perched on the McNear chimney / Photo by Miya Lucas

It wasn’t easy to count them all, as the swifts kept arriving by the hundreds, even while an intrepid American Kestrel tried his best to pick one out of the crowd with no success. The kestrel astonished us all as he dove into a smokestack, either hoping to catch a swift inside or seeking refuge from the ones that had mobbed him when he brazenly chose to perch on the edge of their favorite chimney.

There were so many swifts that evening that some had to seek roosting spots in the other smokestacks. Our keen-eyed volunteers were watching for that, and started clicking away on their counters, their thumbs getting quite a workout, as swifts were diving down into the chimneys at almost ten birds per second.

Years ago, Vaux would seek roosts in large redwood snags but now they’ve adapted to use older brick chimneys, which give them a surface they can cling to for the night. Vaux don’t have feet for perching, just for clinging. (Think crampons like those used by mountaineers.) By gathering together in tight quarters, they not only escape the wind but conserve heat energy, especially important on a long migration through uncertain weather conditions.…