Burrowing Owl docents expand beyond Berkeley

By Frances Dupont

The Burrowing Owls are back!

And this year, Golden Gate Bird Alliance is expanding its Burrowing Owl docent program beyond Berkeley to cover a 30-mile stretch of the East Bay – from Point Pinole to Hayward.

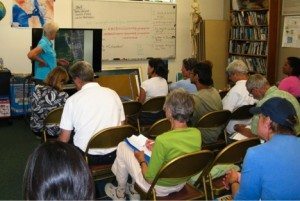

Over 30 enthusiastic volunteers attended the annual Burrowing Owl Docent Training Workshop at the Shorebird Nature Center in the Berkeley Marina on Sept. 28. GGBA now has twenty new docents and 19 experienced docents to cover the expanded area during the 2013-2014 season.

The first owl of the season was officially spotted the day after the workshop by our youngest docent ever – a nine-year-old bird lover who had just been through our training!

The owl showed up within the boundaries of the art installation at the northeast corner of Cesar Chavez Park, where owls have now been observed for up to 10 years. The area includes protective walls and fencing that discourage dogs and people from disturbing the owl, and signs that talk about the Burrowing Owls and other wildlife that inhabit this former dump site.

First Burrowing Owl to arrive at Chavez Park in fall 2013 / Photo by Lyell Nesbitt

First Burrowing Owl to arrive at Chavez Park in fall 2013 / Photo by Lyell Nesbitt

Golden Gate Bird Alliance docents visit this area regularly to help people find and observe the well-camouflaged little owls, using binoculars, scopes, or cameras with large lenses. Docents answer questions about the owls and offer suggestions about how to protect them, including gentle reminders about the importance of keeping dogs on leash along the shoreline trails.

Frances Dupont speaks to Burrowing Owl docents at the annual training / Photo by Della Dash

Frances Dupont speaks to Burrowing Owl docents at the annual training / Photo by Della Dash

The Burrowing Owls come to Chavez Park around the 1st of October after a busy summer raising families somewhere farther north. One banded owl was found to have come from Idaho. A recent study of Burrowing Owls in Washington state concluded that it is mainly the females who come as far south as California, while most of the males stay closer to home.

Because Burrowing Owls are found all along the East Bay shoreline, the GGBA Burrowing Owl program is expanding its scope by attempting to locate and document as many as possible of the shoreline owls between Point Pinole and Hayward. This will be a tough task, considering how well hidden they can be, and that some of the sites where they might be hiding out are inaccessible.

Burrowing Owl in January 2013 by Doug Donaldson

Burrowing Owl in January 2013 by Doug Donaldson

First Burrowing Owl of the 2013-14 season / Photo by Doug Donaldson

First Burrowing Owl of the 2013-14 season / Photo by Doug Donaldson

Burrowing Owl in December 2012 by Doug Donaldson

Burrowing Owl in December 2012 by Doug Donaldson

We know that the owls come to Chavez Park in Berkeley, Martin Luther King Jr.…